The Government seems to have done a U-turn on the issue of

tax exiles. Despite the Programme for

Government’s commitment on the issue, the Sunday Business Post reports that

following an avalanche of submissions from the likes of the American Chamber of

Commerce, etc. the Minister for Finance looks to do nothing. Why?

Because it would undermine investment.

Minister

Brian Hayes was also at it – claiming that tax increases were effectively

over. Minister

Lucinda Creighton backed up her party colleague. And Minister

Richard Bruton also warned against further tax increases on high-income

groups; again, because of that ol’ investment problem.

Do we see a pattern?

If we increase taxes on high-income groups or the business sector we

will lose out on investment. How valid

is this argument?

Let’s bottom-line this:

if maintaining a low-tax regime, whether on high-income earners or the

business sector, is the key to ensuring high levels of investment in the

economy, then that policy has already been judged to be an utter and absolute

failure.

Okay, now let’s work through some arguments.

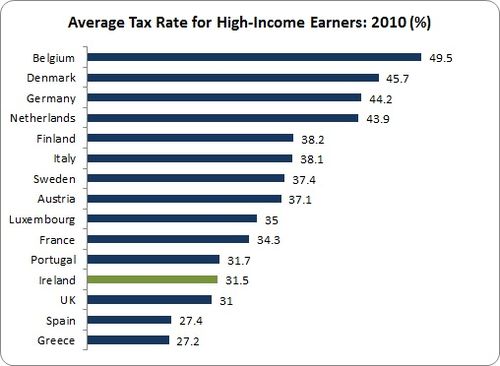

First, Irish high-income earners pay a lower tax rate than

equivalent earners in most other EU-15 countries. The following is from the OECD

Tax and Benefits Calculator, using a two-income household example where one

person is earning twice the average wage and another person earns 1.67 the

average wage. In Ireland, this equals

€118,750.

As seen, Irish high-income earners are taxed at relatively

low-rates. We’re right down there with

other peripheral countries (with the exception of Italy) and low-tax,

high-poverty UK. There has been tax

increases since 2010. The current rate

is 33.7 percent but we don’t know to what extent other countries have increased

taxes. We should also note that the

above doesn’t include local taxation (property taxes, service charges, etc.)

which are higher in a number of other countries. Nor does it include tax breaks (these are

just headline figures).

In effect, in 2010 two-income earners would have to pay over

€6,000 more a year to reach the average of other EU-15 countries; they would have

had to pay nearly €12,000 more to reach the average of other small open economies;

and they would have had to pay over €15,000 more to reach German levels.

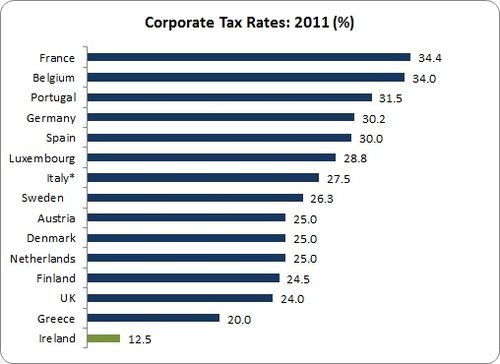

Second, Irish

corporate tax rates are ultra-low compared to other EU-15 countries.

Of course, these are headline rates. Effective tax rates in other countries (after

tax breaks, allowances, etc.) would be lower than the rates above. But so would it be in Ireland – especially given that

Google’s tax rate (as a percentage of gross profits) was

less than one percent.

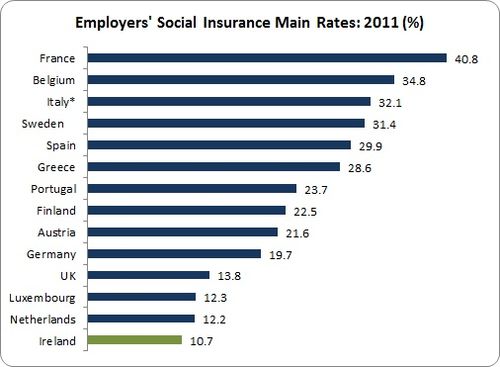

Third, employers’ social insurance (i.e. PRSI) in Ireland is even

lower relative to other EU-15 countries.

We are ultra-ultra-low.

Yes, there we are again – at the bottom.

So what do we have?

All those other countries are doing what we have been warned

against: higher tax rates on high-income

earners and business. This is the type of

thing that would devastate economies according to Fine Gael. Obviously, investment must be flooding out of

those countries. In fact, with such high

tax/insurance rates, they must be facing into an investment crisis.

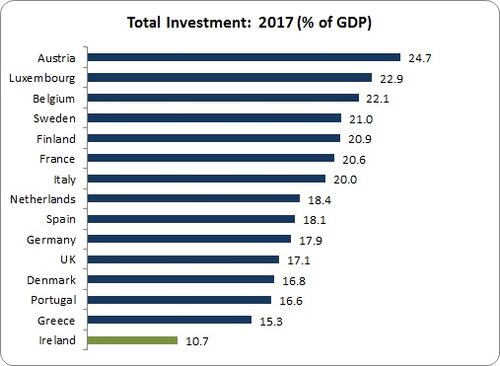

So what level

of investment does the IMF project for these countries by 2017?

Wow. Ireland has

followed the Fine Gal prescription for higher investment and what do we

find? Ireland will have the lowest level

of investment in the EU-15. The average

investment rate in other EU-15 countries is will be 19.5 percent in 2017; the

Irish rate will be almost half. All those countries with higher tax rates on

profits, income and payroll – they will have twice the level of investment.

In short, low-tax Ireland is facing into an investment

crisis.

So is higher taxation a bar to high investment levels? Obviously not; otherwise Ireland would be a

league leader. In fact, higher taxation

can induce higher levels of investment – through higher public investment, public

consumption and progressive social transfers.

That is what we are seeing in other countries.

In Fine Gael’s Ireland, however, we must not scare the

high-income and corporate horses with talk of higher taxation. Otherwise, they won’t invest.

But as we see, they’re not investing anyway. Beyond the insipid tax debate lays a more fundamental

question: what is wrong with our

economic model?

That is one of the key questions for 2013.

Leave a reply to Fintan Cancel reply