When Marge suggests the family go out to a newly opened sushi restaurant Bart demurs.

When Marge suggests the family go out to a newly opened sushi restaurant Bart demurs.

Bart: ‘Sushi? Maybe this is just something one hears on the playground, but isn't that raw fish?’

Lisa: ‘As usual, the playground has the facts right, but misses the point entirely.’

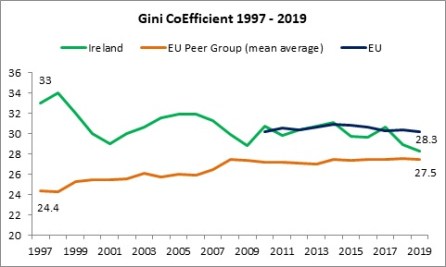

It started with Seamus Coffey’s piece in RTE’s Brainstorm series. This was picked up by Pat Leahy. NERI’s Ciaran Nugent, TASC’s Robert Sweeney and Mick Clifford in the Examiner have waded in while Conor McCabe has been making provocative observations on Facebook around this issue. Who’d have thought the Gini coefficient would cause such a debate.

The Gini coefficient is intended to measure income inequality in society. It ranks countries on a scale of 0 (where everyone has the same income) to 1 where only person in the group possesses all the income; that is, between perfect income equality and perfect inequality. The lower the rating, the more ‘equal’ we are.

Seamus sparked the recent debate by claiming that income inequality was falling in Ireland, contrasted with other countries where inequality is rising.

‘ . . this reduction in income inequality in Ireland gets little domestic coverage. This is surprising given how frequently inequality features on the op-ed pages of our newspapers and in discussions of policy and social outcomes on the broadcast media. At times, it seems like some contributors are more interested in outrage than outcomes and want to ignore the impact of policies perhaps because of their attitude to the people behind them.’

It would appear that Seamus is right – the Gini coefficient has declined.

In addition, another measure of income inequality – the income quintile share ratio which measures the ratio between the top and bottom 20 percent income quintiles – shows a similar trajectory with the Irish ratio falling since the early 2000s so that now it is below (that is, more ‘egalitarian’) than Sweden and Denmark.

Here it is good to remember a fundamental rule of statistics. Data tells you what it tells you. It measures what it measures. The Gini coefficient measures a part of inequality (i.e. income) it does not measure all inequality relationships: wealth, wages, education, access to public services, living standards. No one measurement can capture all that. Each metric comes with insights and limitations. The Gini coefficient has been criticised by economists and statisticians (what measurement hasn’t; think GDP). One researcher stated, after reviewing a range of income inequality measurements stated that ‘income distributions cannot be perfectly summarised in a single number’.

But a more serious problem is how we measure the impact of public services on income distribution, both on income and living standards.

Public Services

There is one major flaw in the Gini coefficient and the income quintile share ratio. They do not include all income – in particular, the income, or in-kind benefit, from public services.

Take childcare for example: childcare in Ireland is the least subsidised in the EU which results in the highest fees. In many other countries childcare is delivered through the public sector at below-market rates, or heavily regulated private and non-profit providers. Let’s assume that it costs €866 per month (o €200 per week) to produce a full-time childcare place.

- Irish households pay, on average, €771 a month for a full-time childcare place

- Danish households pay, on average, €282 a month

In effect, Irish households receive a cash-equivalent or in-kind subsidy of €62 a month (the gap between the production cost and household payment) while the Danish household receives a subsidy of €585 a month. Traditional income equality measurements do not pick this up as it can be categorised as a production subsidy or public service expenditure rather than a cash-equivalent income. Amir Shohan writes:

‘Neglecting public, in-kind benefits when measuring income might give an incomplete picture of the distribution of economic inequality because in-kind benefits such as education, health insurance, and other public services actually constitute approximately one-half of the welfare state transfers in developed countries.’

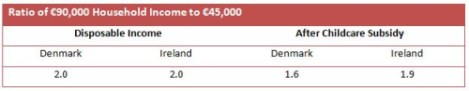

Let’s look at the impact pre and post-childcare subsidy on households. For this exercise I assume two households with €90,000 and €45,000 disposable income in both Denmark and Ireland.

While the ratio of disposable income between the Danish and Irish households are the same (90/45 or 2.0), when we include the subsidy to childcare costs, the Danish ratio falls well below the Irish ratio; that is income inequality is reduced. That is because the income benefits of public services are highly progressive. This simplistic example shows the impact on household income/living standards from public consumption.

This is just childcare. The income/in-kind benefit delivered through other services can have a real impact on equality: GP, healthcare, and prescription medicine; education (schoolbooks, transport, ‘voluntary’ contributions, third-level fees); public transport (e.g. in Copenhagen a monthly pass costs €68, in Dublin it is €130); social, affordable and cooperative housing, etc. Income realised, or expenditure saved, from public services have significant, inequality-eroding impacts. There is no overall database to inform us.

Eurostat and the OECD have acknowledged this omission and have attempted to measure this but it is extremely difficult, with various methodologies being employed and caveats aplenty. In addition, both bodies refer to ‘service quality’. There is little advantage in providing something for free but forcing people to wait for months and years to access the service – so much so that they are forced into the private sector (e.g. Irish healthcare, housing).

In short, the Gini coefficient is not a comprehensive measure of inequality, only income inequality – and it is not even a comprehensive measure of that.

Living Standards

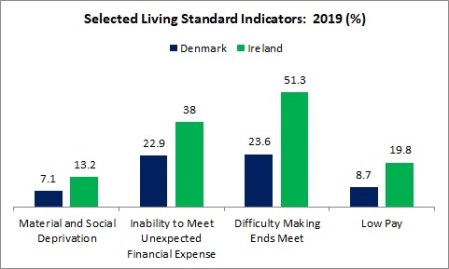

That failure to measure the impact of public services may help explain our poor living standard rankings. For instance, with a Gini coefficient close to some Nordic countries, do we achieve Nordic-level living standards?

- The Gini coefficient in Ireland is only slightly above Danish levels (28.3 and 27.5 respectively)

- The income quintile share in Ireland is slightly below Danish levels (4.03 and 4.09 respectively)

Given this, we should expect living standard measurements to be similar. They are not.

Denmark and Ireland may have similar income inequality measurements but when it comes to some of the living standard indicators, the two are wide apart (here and here and here and here). This should cause its own debate: if Ireland has a decent ranking in income inequality, why can’t we translate this into comparable living standards.

It may be that reduced inequality needs to be baked into the economy and society before we see significant improvements in living standards. Or maybe traditional income inequality indicators miss key inputs (e.g. public services) so that statistical income measurements are not related to what is happening on the ground. Or maybe there is some other factor. This should invite us to work harder to make the connections rather than claiming a single indicator as the definitive measure. Indeed, doing the latter can create popular cynicism when data does not rhyme with lived experience.

We could have a situation where a government de-commodifies a number of important economic and social activities (that is, provide them on the basis of need rather than income): housing, health, education, telecommunications (e.g. broadband), childcare, etc. This provision could substantially increase living standards across-the-board – where deprivation is suppressed and hardly anyone has difficulty making ends meet. But conventional inequality measurements don’t include this de-commodification and, therefore, give an incomplete picture.

Yes, sushi is raw fish. But as the wise Lisa points out, if we focus on the particulars of one ‘fact’, we are in danger of missing the point. Entirely.

Leave a reply to Seamus Coffey Cancel reply