We’re all fiscal expansionists now. From the fiscal orthodoxy to the radicals of the Left there is one message: throw money at it, don’t worry about the deficit, do whatever is necessary and worry about the cost later. Absolutely correct. But progressives should now start debating the implications of that ‘cost later’. Because after the emergency the issue will turn to ‘who’s picking up the bill’.

A good starting point is the ESRI’s current Quarterly Economic Commentary. While normally these contain forecasts, such is the uncertainty that the authors produced a scenario instead. For 2020:

- GDP falls by 7.1 percent

- Unemployment more than doubles to 12.6 percent

- The deficit rises to nearly €13 billion with a deficit-to-GDP ratio of -4.3 percent

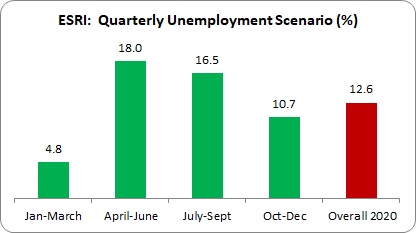

And the ESRI says this scenario could be on the ‘benign’ side; that is, it could be worse. They assume a short sharp hit in the second quarter, with the recovery coming on stream in the third and fourth quarters. However, we don’t know how big the hit will be, when the recovery will start or how robust it will be. There are assumptions layered on assumptions. For instance, the ESRI assumes the trajectory of unemployment to be:

The unemployment rate in the second quarter of 18 percent suggests nearly 450,000 unemployed, falling to approximately 260,000 by the last quarter if the national and international recovery starts in July. However, what happens if the second quarter is worse and the recovery is more sluggish? What if there is no vaccine or effective treatment found by the end of the year? Will we see another round of infections, isolation and lockdowns? Even the fear of a fresh round would depress investment and consumer spending, prolonging the recession.

In terms of the budget, what should have been a surplus in 2020 will now be a deficit of nearly €13 billion in the ESRI’s scenario, or -4.3 percent of GDP. Though the ESRI doesn’t provide a scenario for public debt, we can extrapolate. Based on the pessimistic Brexit budget projections, the Government estimated a debt level of nearly €200 billion, or 56 percent of GDP (97 percent of GNI*). They produced new more optimistic projections earlier this year, but didn’t include debt numbers. However, based on the budget projections, the debt could rise to over 70 percent of GDP and over 120 percent of GNI* under the ESRI scenario. A return to growth should help to bring this ratio down, but it may be some time before it returns to pre-crisis levels.

What can we expect?

1) On the other side of the emergency, the Government will need to engage in another bout of spending to resuscitate business activity. These will be the stimulus measures (the current measures can be better described as ‘disaster prevention’). Those measures may include investment increases (though this takes time to come on stream), VAT cuts, cuts in employers’ PRSI, continued liquidity to businesses, etc.

2) At some point, the argument over fiscal retrenchment will start – to rein in the deficit and debt. It will be austerity but it will be called something else (‘consolidation’, ‘stabilisation’, etc.). However, there could be political limits. For instance, after experiencing a single-tier health system, will people tolerate a reversion back to the two-tier regime and the old normal of waiting lists and over-crowded A&Es? Will people tolerate the reduction of Illness Benefit from €350 per week back to €203?

3) Nonetheless, the fiscal orthodoxy will want to use the pre-crisis levels of public spending as a baseline, even if demand-based expenditure (e.g. social protection, healthcare) cannot be easily reduced. And it is doubtful whether increasing taxation will form a significant part of an austerity/baseline strategy and with some good reason – increasing taxation while an economy is recovering would have the same negative impact it did in the last crisis; but, then, so would cutting public spending.

How should progressives respond? Some starting points to discuss:

- First, the elevated expenditure on health care and income supports during the emergency – on public services and social protection – are not sustainable on the current tax base.

- Second, in the election some progressive parties proposed substantial tax cuts. These proposals should be scrapped. There may be room for limited, forensic tax reductions where social equity and economic efficiency can be shown. But as a rule, tax cuts should be treated as guilty until proven innocent.

- Third, strategies to make the ‘rich’ and ‘corporations’ pay for the crisis will disappoint. For instance, corporate tax receipts will decline in the medium term. This was on the cards prior to the crisis. After the emergency, countries will be even more desperate to find extra revenue. This will accelerate (and rightly so) the clampdown on international corporate tax avoidance. Given that we are a beneficiary of such avoidance, this will hit Irish tax revenue.

And while there is nothing wrong with soaking the rich (or giving them a good splash), higher tax rates on high incomes, withdrawal of tax credits, etc. would make up about 1 percent of total Government revenue. And a new wealth tax would have to take into account the fact that most wealth is tied up in people’s homes, business and farming assets. So, yes, increase progressive taxes but don’t think it will be sufficient to fund a new dispensation.

There are no easy solutions. A key part of progressives’ response should be to explore all the potential and ramifications of fiscal reform. In particular, we should develop a medium-term strategy based on deficit-spending that can still reduce the debt ratio. But this could be hemmed in or curtailed by the return of the fiscal rules and their enforcement by conditional European Central Bank funding.

However, the response cannot be limited to fiscal measures. The fiscal is a consequence of the economic, and the economic is the totality of power relationships.

We need to look at systemic reforms which can lay the foundation for a successful fiscal policy. At the end of the day, getting a few hundred million Euros from the rich, or even a couple of billion, is not the key question (though, please, let’s have it). It is the system that privileges the rich – whether we understand that as individuals, corporate and financial institutions, or simply the logic of capital accumulation; that suborns the productive economy to rentier capital; that excludes or marginalises the role of the producers (a.k.a. the workers).

If we want to ensure the new normal doesn’t end up looking like the old normal, this is the territory we must occupy.

Leave a reply to Niall Cancel reply