Taken together, progressives did not have the best of elections. There will be more detailed analysis in the days and weeks ahead, so this should be considered a small, opening contribution.

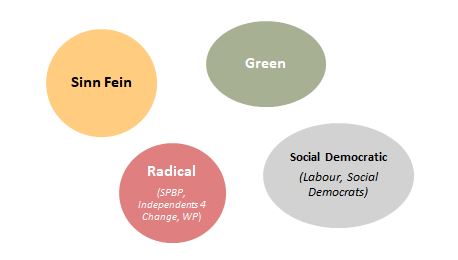

First, which parties are ‘progressive’? This question alone can ensure arguments and splits. For the purposes here there are four broad groupings in the progressive spectrum:

These four groups – Social Democratic, Sinn Fein, Radical and Greens – constitute the broad range of progressive parties. That is not to say that relationships – external or internal – are free of contradictions, tendencies, disagreements; nor do they collectively constitute coherence. But the 2016 RTE exit poll found the voters of these parties to be on the left side of the fence when asked them to self-identify on a Left/Right scale with Left = 1, Right = 10, and Centre = 5).

So how did this grouping do in the recent elections? Let’s focus on the locals.

Overall progressives fell back from 27 percent in 2014 to 25 percent. Sinn Fein’s popular vote fell by 37 percent with the loss of nearly half their seats. Labour’s first preference vote declined as well (by nearly 20 percent) but they managed to gain 5 seats. The Social Democrats’ first time out locally saw them receive 2.3 percent and 18 seats. Solidarity/PBP experienced a similar loss in votes to Sinn Fein, falling from 28 seats to 11. The Greens saw their popular vote more than treble (to 5.6 percent) while increasing their seat total from 12 to 49. The Independents4Change experienced an increase of 0.3 percent (over the United Left result in 2014) but elected only two councillors.

Why the collectively poor performance? First, many progressives have not moved on from the austerity period while people and the economy have. There are more people at work, growing incomes and falling poverty. This is not to dismiss issues such as housing. But without a discourse that places current issues in today’s context, the leaflets are left unread.

In the eyes of many Labour is similarly stuck in the austerity period, unable to break free from their role in Government and chart out a new direction. The Social Democrats will need to translate local gains into national seats but this will be a considerable challenge. All the more so because they share some of the same ideological and social class space as Labour and the Greens.

Only the Greens seemed in step with the times but we should be cautious. Nationally, they received less than six percent of the vote and in Dublin less than five percent of the seats (though had they run more candidates in key wards, they would have gained more). The Greens will need to work hard to consolidate their ‘surge’. Labour in 1992 and 2011, Sinn Fein in 2014, the PDs in 1987 – all saw their ‘surges’ quickly dissipate.

Compounding these individual party challenges is the lack of a common economic narrative. If you were to ask people what progressives stand for they would be hard-pressed to give an answer beyond build more houses, tax the rich, or in the case of the Greens, halt climate breakdown.

Even were progressives able to achieve a consensus, there is no agreement over how that consensus should be implemented. Already, the coalition abacuses are being pulled out: will Fianna Fail woo Labour, will Fine Gael entice the Greens, which way will the Social Democrats go, and will anyone take up Sinn Fein’s offer to join a coalition? Currently, progressives sit on the same of the House. After the next election they may scatter to different aisles.

At root, there is no agreement over long-term goals. Is the aim a progressive-led government? Is it to implement policies within conservative parameters? Is it to grow votes and seats and then figure out what to do? Again, if people were asked ‘What do progressive parties want?’ there would probably be more shrugs than replies.

The 2019 RTE exit poll shows both the opportunities and dangers in achieving a consensus in a complicated public debate:

- 64 percent believe that ‘economic market forces will mean those who work hard will be rewarded’, yet 89 percent believe ‘there should be more policies to resolve the gap between the rich and the poor’.

- 59 percent believe the country is ‘going in the right direction’ (only 29 percent believe we are on the wrong path), yet the majority don’t ‘trust this government to manage the economy and public spending well’.

- 88 percent ‘feel the government needs to prioritise climate change more’ but in an Ireland Thinks poll 60 percent are opposed to a carbon tax (though this poll was taken in January and the climate breakdown debate is quickly evolving).

And in this complication we may be faced with a general election soon. When Ciaran Cuffe was asked by a RTE journalist what advice he would give the current generation of Green members on the issue of coalition he replied the Greens should not enter government on the eve of a recession.

And with a disorderly Brexit, changes in international taxation (which the Government reluctantly accepts), the housing crisis and other external and domestic dangers, a downturn could exacerbate the current downward slope of our economic cycle. Lower tax revenues, more joblessness, rising unemployment costs, pressures on spending, slower growth, rising debt – does the Green Party have a fiscal and economic response? They didn’t the last time and they paid.

But this is not a problem exclusive to the Greens. None of the progressive parties seem to have a response to this, so far opting out of the fiscal policy debate.

Yes, progressives are fragmented. And, yes, we need cooperation. But merely demanding ‘unity’ from the social media side-lines is not an adequate response. We need concrete cooperation strategies.

- Campaigns: The participation of progressive parties and organisations in campaigns such as the National Homeless and Housing Coalition and Raise the Roof are positive examples of cooperation. There are any number of issues – national and local – where this can be replicated.

- Dialogue: this can happen among activists or elected representatives. The key here is that it takes place in safe spaces operating under Chatham House rules and organised by trusted neutrals facilitators. And if all that can be achieved is agreement on the weather – well, that’s a start

- .Open Space: An open online media space (e.g. a website) where progressive parties’ policies, analysis and proposals can be uploaded – if only to show up the similarities. Again, this could be hosted by neutrals.

- Honest Broker: or such brokers (individuals, non-party civil society organisations) could assist in dialogue between the different parties without prejudice, even if it takes the form of proximity talks.

And patience. It would be nice to think progressive forces might coalesce around a set of minimum demands to campaign on with a view to acting with cohesion after the next general election but there might not be enough time or interest, too much suspicion this side of a vote. We might have to wait a while.

We need a new popular front, a broad coalition of progressive parties, individuals and groupings. We need to ditch sectarianism and pre-conditions. Progressive cooperation is about persuading, not hectoring; leaving the door open to all, not closing it to some. It is not about abandoning principles. We do not lose our ideological convictions or strategic preferences because we seek a cooperative relationship with those who don’t share them all right down the line. But I know this.

We undermine our convictions and preferences if we don’t cooperate, seek out allies, come to new understandings. That’s a dismal road where we are all losers. And we have travelled that road long enough.

Leave a reply to Diarmuid O’Flynn Cancel reply