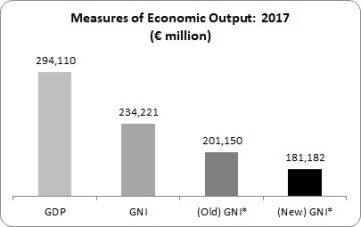

Last year the CSO introduced an innovative measure of national output in order to remove the distorting effects of multi-national activity (re-domiciled companies, R&D and aircraft leasing). It was called modified Gross National Income or GNI*. Now they have modified the modified GNI. And our level of output has been revised downwards.

The recent modification reduced our national output by 10 percent. In other words, we find ourselves 10 percent poorer than we thought.

We have also found ourselves deeper in debt. When measured against GDP, our general government debt was 68 percent last year – below the Eurozone average. However, when measured against the old GNI* our debt level went up to 100 percent. Now we find that our public debt is 111 percent of the new GNI*.

So, poorer and deeper in debt; and now we may find ourselves on the wrong side of the economic cycle. In the years since the end of the recession / stagnation, all our indicators have been in fast growth. This was never going to last; it was a result of pent-up demand and foreign direct investment. Eventually it would settle down. But we may be settling down earlier than we thought – and at a lower level than we thought. Let’s look at two indicators that are fairly detached from multi-national activities: personal consumption (consumer spending) and employment.

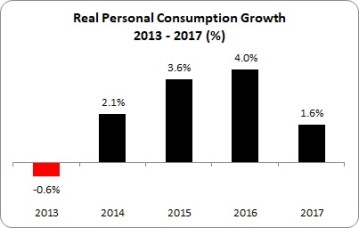

Personal Consumption

Personal consumption grew at a steady pace but the increase fell off significantly in 2017.

Consume spending reached 4 percent in 2016. However, growth suddenly cooled off at 1.6 percent. This was not anticipated. Early last year:

- The Government anticipated consumer spending to fall off by a marginal 0.2 percentage points in 2017

- The ESRI expected consumer spending to marginally increase over the 2016 level

- The Central Bank did expect consumer spending to fall off – by 0.9 percentage points. But this was more optimistic than the actual 2.6 percentage point fall.

It should be noted that in the first quarter of 2018, consumer spending actually fell on the previous quarter:

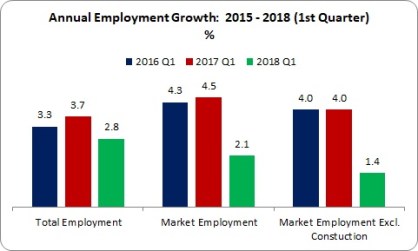

Employment

We see a similar fall-off in growth in employment. The following measures annual increase up to the first quarter.

We find that total employment growth fell off in the year up to the first quarter in 2018. However, the fall-off was significant in the market economy (essentially the private sector, this excludes public administration, education, health and agriculture). Growth fell by more than half. And if we exclude construction, the fall-off was even more marked.

Again, only the Central Bank expected a fall-off close to this magnitude.

* * *

What does all this mean?

- Growth rates immediately coming out of the recession and stagnation were never going to be maintained. They should ease off to more sustainable levels. However, there are signs that the levelling off is occurring earlier than expected and potentially at lower levels than projected.

- The easing off of consumer spending and employment could be blips that will correct themselves this year. The Central Bank, while expressing surprise at the low levels of consumer spending last year, is nonetheless confident that it will rise again this year. We will have to wait and see whether the confidence is justified.

- What happens if and when all those ‘known unknowns’ come down on us? Brexit, corporate tax reform (coming from the EU and the US), interest rate increases, a looming deficit in the Social Insurance Fund, trade wars, climate change, housing shortages, over-heating, concentration of tax/production in a few multi-nationals, etc.

Then there’s the ‘unknown unknowns’. We can’t break this down because, well, they’re unknown.

There is a fear, understandable given our recent experience, that any of these factors could lead to another recession. However, it doesn’t have to be as dramatic as that. We could enter a period of low-growth – so low that it feels recessionary. In the 1980s it certainly felt like a recession but in actual fact the economy grew during most of that period – it just didn’t grow much.

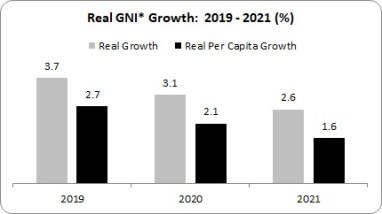

So let’s look at the Government’s per capita projection for the next three years.

By 2021, real per capita growth will be 1.6 percent. It wouldn’t take much to knock those numbers downwards.

The challenges are considerable. Future fiscal policy will need to engage in debt-reduction, drive investment, close the deficits in our social infrastructure (housing, education, health, etc.), and avoid over-heating – all the while keeping within fiscal rules which even the Department of Finance believes are ‘dangerous’. What a balancing act.

Progressives and trade unionists need to seriously debate the Government's fiscal policy. If we don’t, then we may find them using the same or similar deflationary tools that gave us austerity. And given our experience of that, it wouldn’t be good for vast swathes of working people.

Leave a reply to Michael Taft Cancel reply