Cuts in Child Benefit, Youth Programmes, school capitation

grants, higher education, student grants, youth unemployment payments – the economic

war on youth has run into hundreds of millions and cost the life-chances of hundreds

of thousands: emigration, unemployment, falling wages. At the start of this crisis who would have

imagined this war would have run for so long and been so destructive?

The first rule in an economic war is to discredit the

victim. One of the most malicious comments during this

crisis was aimed at youth (though attacks on public sector workers were equally

outrageous) and came

from a Labour Minister:

‘What we are getting

at the moment is people who come into the (social protection) system straight after school as a

lifestyle choice. This is not acceptable, everyone should be expected to

contribute and work.’

Yes, there are so many jobs available but our lazy, lazy

kids choose to hang around the house

in their underwater drinking Red Bull and watching DVDs all day. We have to incentivise their indolent backsides. And cutting youth unemployment payments is

one of those ways.

It’s bad enough to suffer cuts – in public services, income

supports, job, wages. But then to be

told that you are to blame . . . And then to be told that you are lazy, too . .

.

This may make for some popularity among the Sunday

Independent, populist, socially-vindictive set.

But it is wrong, terribly wrong, demonstrably wrong. And it diverts attention from the real

issues, as scapegoating is intended to do.

It has been pointed out by many commentators that there are

approximately 32 unemployed for every job vacancy. This is a national average. It is likely to be higher for younger

people who are disadvantaged in the labour market (e.g. less job experience)

unless they possess skills in labour shortage areas. This alone tells us a lot. But there’s another way to approach this

issue.

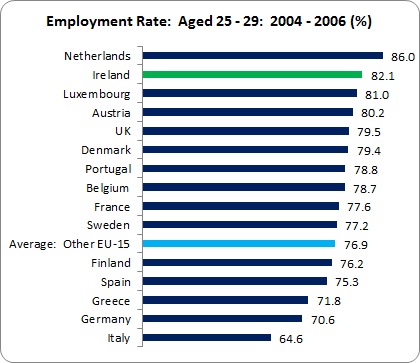

If there is a gene in the Irish youth make-up that predisposes

them to sloth, we should be able to historically track it. The following two graphs refer to the ‘employment

rate’ as measured by Eurostat. The employment

rate is the proportion of the working age population in employment. This is a better measurement than the

official unemployment rate which can be altered by administrative rules.

So what did our lazy kids do prior to the crash? They worked.

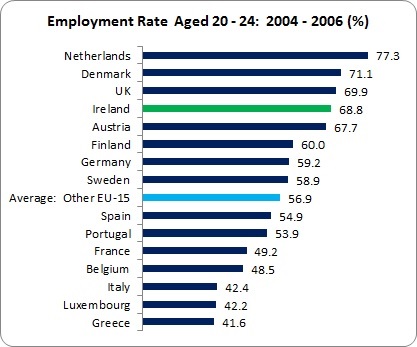

For young people aged between 20 and 24, the Irish

employment rate was the fourth highest in the EU-15 – considerably above the

average of other EU-15 countries.

However, we must be aware that in this age group there would be a high

level of young people still in education.

But of those in the workforce, nearly 70 percent of Irish youth were

working.

Looking at the employment rate for those aged between 25 and

29 years is helpful as almost all of this group would have left education. How do the Irish hold up in the lazy

stakes? Pretty poor, actually. People were just too determined to work.

The employment rate for Irish people in this age category

was the 2nd highest in the EU-15.

We even ‘worked harder’ than the hard working Germans – much harder.

What does this tell us?

It’s quite simple. Young people

didn’t need social protection cuts to be incentivised to work hard – in 2004 to

2006 unemployment

payments actually increased by an incredible 32 percent but still people

preferred to work; they didn’t need to be threatened to have their dole cut if

they didn’t take up that JobBridge

internship in a petrol shop in Mullingar; they

didn’t even need a letter from the Department telling them it’s better to work

– they had figured that out all on their own a long time ago.

All that was necessary to establish a high employment rate

was work availability. And that’s why in

both the age categories, the employment rate has crashed. For instance, for the 25 to 29 age group, the

employment rate has fallen from 2nd highest pre-crash to 4th

lowest in 2012, just above other peripheral countries. Why

has it fallen? Because the pool of available work is too small.

It’s that simple. It’s not about being lazy; it’s not about

incentivising young people; it’s not about lecturing them or hectoring them or

hassling them. It’s about putting more

jobs in the work pool.

Unfortunately, in the economic war on youth, there’s a

drought – and young people are blamed if they don’t go around rain-dancing hard enough.

Leave a reply to David Cancel reply