Let’s assume the Government comes up with the best house-property

tax ever devised – truly progressive, taking into account all the social

factors such as unemployment, low-income, arrears, and mortgage equity (or lack

of). Yes, it’s a big assumption but let’s

try it anyway. If this occurred there is

still a strong argument that the Government should not introduce such a tax

next year or even the following. And

that is because the economy and hundreds of thousands of households cannot

absorb it. Let’s run through some of the

arguments.

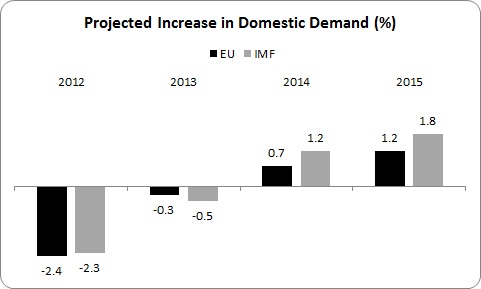

First, the domestic-demand recession is expected to continue

next year – the sixth year in a row.

As seen, both the EU and the IMF expect domestic demand

(consumer spending, government spending on public services, and investment) to

fall again next year. They both estimate

that consumer spending will fall, as more people wilt under the combination of

austerity measures, falling incomes and unemployment. Even by 2014, domestic demand will start

rising but only marginally.

While under normal growth conditions, a house property tax

would be an efficient tax – limited impact on the domestic economy and more

efficient at reducing the deficit; relative to spending cuts. Even so, the impact on consumer spending

would be high: for every €100 raised in

a house-property tax, there is a resulting reduction of approximately €75 in consumer

spending. In normal growth situations,

the economy would absorb this. But as we

know, these are not normal times. So

what would be the impact of introducing such a tax while the economy is still

in a domestic-demand recession?

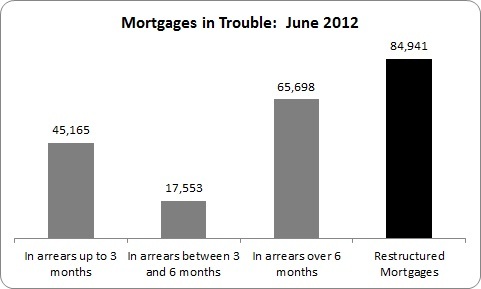

Second, what would the impact of such a tax be on mortgages

in trouble? The

Central Bank reports the following.

In June, 28 percent of all

mortgages were in arrears or were restructured (interest payments only, reduced

payment, payment moratorium, etc.). That comes to 213,000 mortgages. Even

more worrying, 34 percent of the value of all mortgages are either in arrears

or has been restructured.

This picture is getting worse. Back in September last year there were

183,000 in arrears or restructured. There

has been an increase of 16 percent in troubled mortgages in the last nine

months. And there is no sign that the trend

has topped out.

Question: is it a

smart idea to introduce a house-property tax with so many mortgages in trouble?

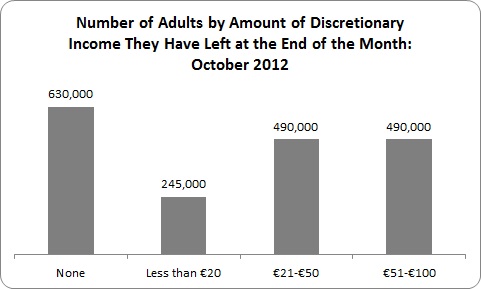

Third, the League

of Credit Union’s What’s Left Tracker shows the low and ultra-low level of

discretionary income people have at the end of the – that is, what’s left after

tax and essential bills. The numbers are

staggering.

1.9 million – over half – have less than €100 at the end of

the month. Though not everyone in this

category will own a house (such as public and private rented tenants) there

will be a sizeable proportion who will be subject to a house-property tax if it

is implemented. And though this is a

subjective measurement (it is left to people to determine what an essential

bill is), what is worrying is that this number – 1.9 million – has increased by

over 50,000 in just three months. It is

a strong indicator of the high number of people on the edge.

Fourth, real wages are projected to fall next year. The EU projects that wages (employee

compensation) will fall by 1.3 percent after inflation. The IMF and the Government are less

pessimistic – projecting falls of -0.2 and -0.3 respectively. The ESRI projects a real wage fall of -1.8

percent, using the Consumer Price Index.

Whichever is more prescient, they all agree – wages will fall after

inflation. With living standards falling,

what will the impact be of introducing a new layer of taxation?

What we have left is a grim set of indicators of continuing

recession, growing arrears and falling income.

It is questionable how much more the economy can take – never mind the people

who populate that economy.

There will be the claim that the Government has to get money

from somewhere. Yes, of course, but here

is the problem – if you introduce new taxation measures on a depressed economy

and an even more depressed society, you won’t get the money, whatever the

budget line promises. For the extra

taxation results in people reducing their spending; businesses react to falling

turnover by squeezing their payroll through cutting wages, working hours and

even employment. This, in turn, leads to

depressed tax revenue and higher public spending if there are job losses. And, so, the deflationary cycle continues its

downward slope.

None of this argues against the principle of a house-property

tax, only its timing (though I hold heretical, minority thoughts on the

subject: houses, when consumed as homes,

should be exempt from recurring taxes; houses, when used for a capital gain or

income, should be taxed appropriately – but I accept this will probably not get

much traction).

Of course, there is the issue of the design of the tax –

will the Government tax all property – housing and financial? If it excludes the latter it will be giving a

substantial subsidy to high income groups.

Will the house-property tax be progressive? And how will we know if they don’t measure the

income-distribution impact (don’t hold your breath). How will it treat low-income earners,

unemployed, those in arrears, etc.

The point in this post, however, is the fiscal timing during

a period of stagnation. In the

medium-term taxation will have to increase (and Donagh

Brennan poses this issue with clarity).

But smart fiscal consolidation lays down a few principles. Before taxation rises we must first return to

reasonable growth – employment and real wages.

This will broaden the tax base and make it easier for households to

absorb the increase without a negative impact on consumer spending. Before taxing houses, we can add another

principle – we need a substantial write-down of mortgage debt. Otherwise, we will be taxing arrears and

debt, rather than equity.

So where do we get the money in the short-term, while

introducing measures to lay the foundations of growth and debt write-down? The

Minister for Finance provided the answer to the Dail:

‘The Deputy (Seamus Healy) referred to the wealth

tax in France, which is at 1.5%. On a pro rata basis, that kind

of tax in Ireland would have a yield of €400 to €500 million per annum.’

Hmmm. Here is a

property tax, a comprehensive property tax which includes both housing and

financial property, a tax that would have minimal impact on domestic demand as

it would hit only a tiny proportion of households, a tax that would raise up to

€500 million. That’s the same amount the

Government has said it wants to raise from a house-property tax.

Isn’t it time to pursue smart fiscal consolidation?

Leave a reply to smart homes Cancel reply