Well, that was peculiar. An ESRI working paper that estimated the cost of going to work was published made the top story on RTE Six One news and then was withdrawn only a few minutes after being featured. Controversially, it said that 44 percent of families with children would be better off on the dole than at work. The ESRI issued a statement explaining its withdrawal but already the drumbeats were sounding: ‘disincentive to work’, ‘dole is too high’, ‘can’t get people to work for me’, etc.

Conspiracy theories will no doubt circulate – about how the Government forced the withdrawal of an ‘inconvenient’ paper. A number of social organisations will be relieved – with a Government already hammering social protection recipients, it would have just added more weight to the hammer. What are we to make of it?

The document in question – ‘The Cost of Working in Ireland’ – is a working paper that was published with the usual rider: an ‘un-refereed work-in-progress by researchers who are solely responsible for the content’.

The conclusion was the bombshell:

'The evidence presented in this paper suggests that the costs of working are high. Expenditure is higher for those in work than out of work. For an employed person without children the additional costs of working sum to some €140 per week, or almost €7000 a year. This increases to €9000 when there are young children in the household!

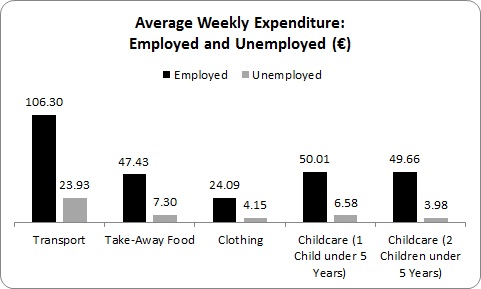

The employed may have a higher disposable income but they spend more on clothing, transport, childcare and eating out. . . . Employed people incur 5 times the costs of an unemployed person.'

This is important for policy as it substantially affects the incentives to work. A comparison of take home pay shows that it does not pay to work for 1% of the population. However, a comparison of take home pay plus extra expenditures shows that 15% of the people without children, and 44% of people with children, are better off not working.

‘In a statement, the ESRI said the decision to withdraw the paper had been made "as it has emerged that the underlying analysis requires major revision and that the paper's estimates overstate the numbers of people who would be better off on the dole than in work”.

And to add to the story’s spice, Professor Richard Tol, one of the three co-authors, was on Morning Ireland, standing by his work, suggesting that the Government and even the trade unions may have had a hand in getting it withdrawn (trade unions?!).

So what are we to make of this? There are three issues but let’s state first: the paper, in general, only states the obvious – that there are costs associated with working (childcare, transport, eating out). . Further, its findings, rather than give support to the ‘dole is so high no one will go back to work’ argument, actually undermine this unsubstantiated claim.

Stating the Obvious

Is the methodology sound? It is a technical paper (involving binary-dummies, logit regression, Heckman selection model, a rho discounting function, etc.) working with two separate data sets – the CSO’s household budget survey and the EU Survey on Income and Living Conditions. When working with two datasets with different purposes and methodologies, one has to take special care. This is what the paper found.

I won’t comment on the scale of these expenditures (that could be part of what the ESRI claims is a deficient methodology). The point here is that higher expenditure on things like transport and take-away food for those in work is not surprising. It is, on average, more expensive to go to work than not. As to whether the methodology and, so, the actual numbers are sound – well, we shall have to watch the upcoming row between the ESRI and the authors of the report.

No Disincentive to Work

The above findings are based on data from the Household Budget Survey conducted in 2004/2005. While the numbers in the paper are updated, the gap between expenditure by employed and unemployed would have been evident – though the prices and incomes will have been lower.

For instance, according to the CSO weekly childcare expenditure in 2004/2005 was €14.07 for ‘employed’ while it was only 64 cents for unemployed (this is not directly comparable since the ‘employed’ category includes part-time workers while in the paper only ‘full-time employees’ were used). In all the categories the paper mentions, there were substantial gaps in 2004/2005 – quite possibly of similar proportion given price and wage levels.

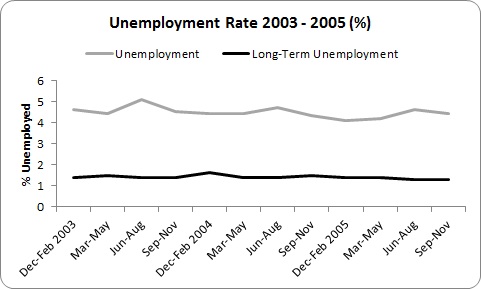

So here is the question: if such gaps were present eight years ago, surely this must have provided a substantial a disincentive to work – with tons of people choosing to stay on the dole rather than work. Did it? No.

Eight years ago, we had an employment rate that was as close to ‘full employment’ as you can get.

Not only did we have low unemployment – we had one of the lowest rates of long-term unemployment in the EU. If there were ‘life-style’ choices being made – better to be on the dole than at work – the long-term unemployment figure should have revealed this. It doesn’t.

Of course, this includes everyone. What about those families with children – the claim that a substantial percentage would be better off on the dole would have a foundation in the 2005 data? However, we find very few families on unemployment payments.

- There were 6,900 recipients with children on unemployment benefit

- There were 15,800 recipients with children on unemployment benefit.

- These recipients made up only 18 percent of all recipients during a period of ultra-low unemployment rates

Of course, many (most?) of these recipients would have been in transition from one job to the next. Given that there were over 1,000,000 families with a child benefit payment, this doesn’t suggest that higher at-work costs were a disincentive to work.

We will discuss this in more detail below but the point here is that the relationship between unemployment payments and after-work disposable income is not one that ‘disincentivises’ work.

The Wrong Angle

No surprise that the immediate reaction is that dole payments are too high. You can make more on the dole than at work. This discourages workers from taking up jobs where they exist. What’s the solution? Why, cut social welfare, of course.

Oh. We’ve cut social welfare twice. In 2010, 38 percent of unemployed suffer from deprivation experiences. 30 percent of children suffer from deprivation experiences. Further cuts will, of course, drive this figure higher (it will no doubt rise when the 2011 data comes on stream). Not only is poverty rife among those dependent on social protection, there is a poverty of knee-jerk responses.

The problem is that we are in danger of looking at this problem from the wrong perspective. There are two issues here.

First, is the level of income from work too low? Obviously something is wrong when 23 percent of households with one person working are suffering from deprivation experiences. This is higher than the national average. We never ask are wages low – we seem, for some bizarre reason, to think that’s a good thing, despite the toll it takes on the economy and the Exchequer.

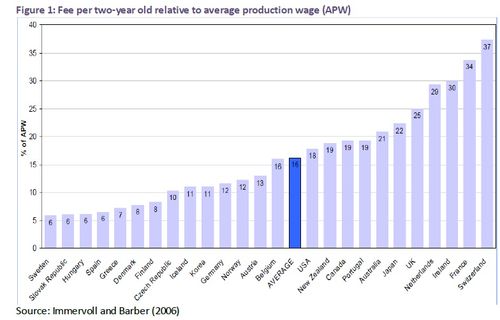

Second, the issue is not that the social welfare system is too generous. The problem is that it is not strong enough. The ESRI working paper produces an interesting graph.

Irish childcare costs are the third highest in the countries surveyed here – twice the average level of costs and 5 times the cost in Sweden. A strong welfare state would have a universal low-cost public childcare system. Even the working paper states:

‘Affordable childcare services are also important for the development of the child . . . a safe, stimulating and social environment for children which can have long-term benefits for socioeconomic integration.’

We don’t have this.

Nor do we have other social supports for people in work – notably, free GP care and (low-cost) prescription medicine. Or a truly free public education system – in other countries school books and transport are free or very low-cost (and they don’t need ‘voluntary’ payments).

A strong welfare state significantly reduces costs for all people – in work or not. But we don’t have such provision. We have some provision for those without a job. But once you get a job, the welfare state doesn’t exist in many key sectors. This is the key issue – the lack of a proper welfare state.

* * *

The ESRI working paper suggests that the gap between social protection income and work is not the issue regarding job take-up. It certainly didn’t exist back in 2004/2005 from which the base data is derived.

What it does show up is the weakness of the welfare state, especially in comparison with other European countries. Of course, we will get the complaint that we can’t afford a strong welfare state. As has been argued time and time again on this blog, we can’t afford not to have a strong welfare state. People’s living standards – whether through low cost childcare, truly free education, state-funded earnings related pensions, strong safety nets – these are not obstacles to recovery, they are essential components of that recovery.

What disincentivises job take-up? The lack of jobs. The EU shows that there are 26 unemployed for every vacancy. That’s as big a disincentive as you’re going to get. Where there are jobs, the issue of social welfare payments and even low-pay become almost marginal. People want to work. They can’t find work because there is no work.

Still, we may be heading back down the same old road we’ve been before – cutting social welfare rates and supports. If we do, demand will be cut from the economy, jobs will be lost, the recession will be extended which will only result in more calls for cuts.

When will we learn?

Leave a reply to ciaran Cancel reply