Brian Lenihan and Patrick Honohan inform us that the EU/IMF deal is not written in stone, that it can be ‘renegotiated’ (even, it seems, the interest rate). For progressives, the issue of renegotiation is paramount for, as it stands, the bail-out would force us into (a) squandering our assets and cash (Pension Fund, NTMA cash balances) on a futile attempt to bring the deficit into Maastricht compliance by 2014/2015; and (b) piling private bank debt on to sovereign debt. So what is it that we should be demanding in a renegotiation? What are the key points to rally a consensus around?

The first question is: what does the EU/IMF really want? The answer is fairly straightforward.

- After three years, they want the Irish economy to re-enter the international bond markets.

Full stop. That’s the end-game. Anything that brings us closer to that is good, anything that takes us away from that is bad. What are the conditions upon which the Irish economy can re-enter the international markets? Or, put another way, under what conditions would markets begin lending to the economy at a sustainable rate?

- That the Irish economy is capable of generating revenue to pay off future debts.

That’s it. There’s no debate over the end-game, only means. On this basis we can put Honohan’s comments in perspective:

‘We can be confident that, if a new government were to want to substitute alternative measures which were both economically efficient and of equal fiscal effect, it would receive a sympathetic hearing from the funders.’

That poses no problems for progressives. As has been shown (here and here), an investment programme combined with ‘growth-friendly’ fiscal consolidation policies would not only have ‘equal’ fiscal effect, but better, far better.

Of course, many will – with some justification – claim the IMF / EU are so ideologically blinkered that they will insist on an austerity programme, regardless of how it impacts on our ability to exit the Stabilisation Fund in three years time without a default. Maybe. However, the best argument against any escalation of commitment that the IMF / EU may suffer from in the future is . . . their own projections.

A key metric that will determine our re-entry into international markets will be the ‘debt-sustainability’ measurement. This measures how sustainable our accumulation of debt is. If the interest rate on the debt (as a percentage of GDP) is higher than the nominal GDP plus the ‘primary’ budget balance (the ‘primary’ balance excludes interest payments), then the debt can be considered unsustainable. If the interest rate is lower, then it is sustainable.

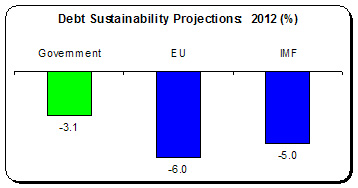

This is what market analysts will be examining, among other things. So how does this play out? Let’s compare the projections put forward by the Government, the EU and the IMF for 2012 – the year before we are to exit the Fund. We will use the Government’s projected interest rate of 3.9 percent (as a percentage of GDP).

The Government believes that by 2012, considerable progress will be made in both reducing the deficit and promoting growth. The EU doesn’t. The IMF is slightly more optimistic than the EU – but their projections were published in October; since then, all forecasters have revised growth downwards and the deficit higher.

The Government believes that by 2012, considerable progress will be made in both reducing the deficit and promoting growth. The EU doesn’t. The IMF is slightly more optimistic than the EU – but their projections were published in October; since then, all forecasters have revised growth downwards and the deficit higher.

Even with the IMF’s more optimistic projections, though, the Irish economy will still be in negative territory even in 2015.

However, the shrewder in the markets will also be looking at debt sustainability under GNP. They will realise that our GDP suffers from a soufflé effect owing to the impact of a modern multinational sector that is at times only tangential to the Irish economy. What would the numbers look like then?

- According to the EU projections, debt sustainability would deteriorate to -7.6 percent.

Therefore, the question we can ask the EU is: do you really think, on the basis of your own projetions, that markets would lend to us? The answer is obvious.

And while otherwise fiscally healthy economies can survive a couple of years in negative territory, especially during a recession, an economy with a debt of 114 percent of GDP (the EU’s estimate for 2012) is not healthy.

Even though this will be an important measurement for debt analysts, it will not feature in the economic debate here. After all, we were told by domestic commentators that all throughout 2009 and 2010 (until it became untenable) that international markets were ‘impressed’ with out austerity budgets and that we were not like Italy, Spain or Portugal. This despite the fact that since early 2009 Irish borrowing costs were the highest in the EU-15, save for Greece.

So what does the IMF/EU want? For Ireland to be able to exit the Stabilisation Fund and return to borrowing on international markets by the end of 2013. On their own projections this is not likely to happen.

This opens the door to renegotiation – using their own data. This opens the door to an alternative economic programme, one that prioritises growth because that is a key element in the debt sustainability measurement; one that emphasises deficit reduction through employment, in order to raise revenue and cut unemployment costs.

There is much to have a chat about.

Leave a reply to Michael Taft Cancel reply