There is much commentary about our strong export growth in 2010 and the knock-on effect on corporate tax revenue which came in about 24 percent higher than what the Government expected (though in comparison with 2009 there was only a fractional increase). Clearly for a small open economy export growth is vital. However, there is confusion between export growth, which is positive, and Ireland’s particular export growth model, which is skewered. For not all export models are equal.

Ireland’s model is primarily based on multi-national activities which, if we are to believe the brochures, are here because of our ultra-low tax rates and accommodating transfer-pricing regime. Indigenous exports, however, play only a minor role.

We know that export growth contributes to an Irish GDP that looks better than what it actually is (what is called a soufflé effect). But what kind of contribution does Ireland’s export growth model make to the economy? One way of measuring this is to calculate what is called the Direct Economy Expenditure. This measures expenditure in the Irish economy on payroll costs, Irish-produced raw materials and Irish services. After all, growing exports and, so, growing production should produce increased employment, wages and PRSI along with purchases of inputs from local companies.

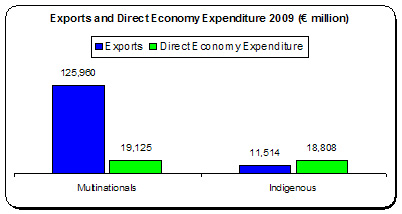

We’re all familiar with the 90-10 divide. Multinational exports make up 90 percent of all our goods and service exports, with chemicals being the heavy hitter – constituting nearly a third. The following comes from Forfas’s latest report on agency-assisted enterprises, which make up 90 percent of all exports – the main omission being IFSC companies (agency-assisted enterprises are by-and-large export oriented).

We find that while multinationals exported nearly €126 billion, they spent only €19 billion in the economy. This low amount arises from two factors: one, the modern multinational sector is capital intensives (meaning relatively small payroll contributions); and, two, they import most of the goods and services they use in their production.

The indigenous sector, however, spends more in the economy than they export. This arises because many Irish firms – notably the Food sector – sell into both the export and domestic sectors; they are more labour intensive; and, crucially, they purchases more their production inputs from local companies.

That is why that, while indigenous exports made up less than 10 percent of all export value, they nearly equal multi-nationals in their contribution to the economy.

Another way of looking at this is to compare expenditure in the economy with the value-added produced. Value-added is another way of computing GDP. If we exclude agriculture, construction and public administration, we find that the agency-assisted enterprises made up 60 percent of all value added in the economy, of which 49 percent is made up of multi-national companies.

How does direct economy expenditure compare to value-added produced by the two sectors?

- For every €1 value-added produced by multi-nationals, only 31 cents is spent in the economy.

- For every €1 value-added produced by indigenous companies, €1.45 is spent in the economy.

Indigenous companies give far better bang for the buck. The implication is clear: if modern multi-nationals drive exports in the future, it will have a positive impact on our headline GDP figures (We’re growing! We’re growing!). However, the impact on the economy will be less than the sum of all the parts.

Of course, this can easily lead one to the slogan ‘Build Our Indigenous Sector!’ No one disputes that. But sloganeering is one thing, concrete strategies another. If we maintain current policies, built around the belief that market processes will sort everything out, we will be in a world of hurt. Consider two points.

First, between 2000 and 2008 multinational exports grew by €53.7 billion while indigenous exports grew by €3.5 billion, or about 6 percent of the total export growth. That was during a period of solid EU and global growth. If that was all indigenous companies could grow then, consider what the next five years is going to be like.

Second, as Finfact’s Michael Hennigan points out:

‘The full-time jobs level in the international tradeable sector is now at 268,000 – the same level as in 1997 when the workforce was 25% smaller.’

That puts our hollow export model into perspective.

Leave a comment