Why did I think the Ernst & Young forecasts wouldn’t make big news? Did I really imagine that its key projections on the deficit and employment would provide a sobering counter-point to all the ‘whistling past the economic graveyard’ commentary we get everyday. Yet, the analysis is worth poring over in detail, not because E&Y are blessed with special prophetic powers (it is, after all, a projection); but because (a) it is the most detailed of any of the private independent forecasters; (b) it supports the Government’s fiscal strategy; and (c) ironically shows that the Government’s strategy will fail. Fail badly. Truly and utterly fail.

Why did I think the Ernst & Young forecasts wouldn’t make big news? Did I really imagine that its key projections on the deficit and employment would provide a sobering counter-point to all the ‘whistling past the economic graveyard’ commentary we get everyday. Yet, the analysis is worth poring over in detail, not because E&Y are blessed with special prophetic powers (it is, after all, a projection); but because (a) it is the most detailed of any of the private independent forecasters; (b) it supports the Government’s fiscal strategy; and (c) ironically shows that the Government’s strategy will fail. Fail badly. Truly and utterly fail.

Let’s look at two key metrics: employment and the deficit. First, E&Y predicts a jobs-recession of 15 years. In other words, we will not reach pre-recession levels of employment (i.e. 2007) until 2022. Think on that for a moment; but not too long – it will do your head in. That’s why E&Y projects unemployment – even with high levels of immigration – will remain in double-digits for well into the decade.

Of course, unemployment doesn’t rank all that highly on the current agenda. It’s all about the deficit, deficit, deficit. Which is why it is curious, even downright bizarre, that E&Y’s projection on the deficit didn’t get more news. For they projected that, on current trends, the budget won’t return to Maastricht compliance until 2018 or 2019. Wow. The whole premise of the Government and allied deflationists is to bring the deficit under control (that is, below -3 percent of GDP) by 2014. Hence, the cuts, cuts, cuts. Yet, according to E&Y, this won’t happen for nearly a decade.

So, a decade of high unemployment and a bloodied national balance sheet – doesn’t anyone in Government buildings get it? Laurence Summer, chair of President Obama’s Economic Advisory Council gets it:

‘(It is) impossible to sensibly address either unemployment or long-run fiscal challenges in isolation.’

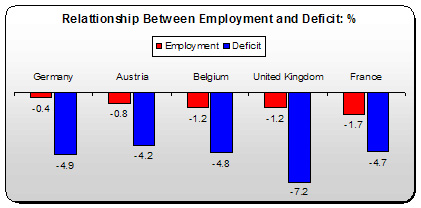

And other EU countries get it. Let’s compare employment loss and deteriorating deficits. My proposition is simple: those countries that best protected employment suffered less fiscal damage. How does this hold up, going from 2007 to 2011 (2008 for employment when most economies entered the jobs downturn)?

Those countries that kept employment losses below the Eurozone average (-2.5 percent) were the most successful in containing the fiscal damage, with the exception of the UK (and, as we will see below, we’d be grateful of even the UK’s fiscal slide). These countries kept their balance sheets contained – with deficits sliding by less than -5 percent.

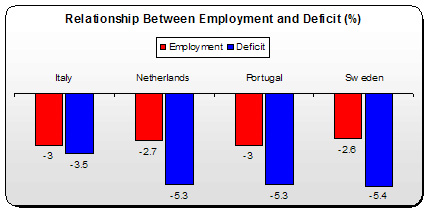

For countries that saw their employment fall by more than the Eurozone average but not by much, the story is much the same:

These countries fiscal situation fared slight worse in tandem with less success on the employment front – but not qualitatively so. The slide was still in the ‘containable’ category.

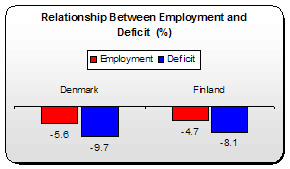

When we get to countries with higher employment losses, what do we find? A deteriorating balance sheet.

Denmark and Finland found their employment levels falling by considerably more than the Eurozone average. This coincided with more substantial deficits – much more so than the countries above.

Denmark and Finland found their employment levels falling by considerably more than the Eurozone average. This coincided with more substantial deficits – much more so than the countries above.

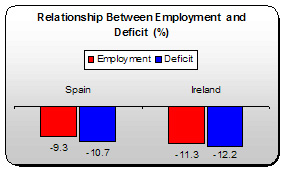

Who were the two worst performers? Spain and Ireland. Both saw their employment levels fall through the floor. How did their fiscal situation fare?

Spain has seen employment fall by nearly 10 percent; their deficit slid by a similar amount.

Ditto, but worse for Ireland. Employment fell by over 11 percent; its deficit falls even further.

Ditto, but worse for Ireland. Employment fell by over 11 percent; its deficit falls even further.

What can we conclude from all this? Those countries that succeeded in minimising jobs losses were also successful in minimising balance sheet losses. Conversely, those countries which experienced high levels of jobs losses suffered greater fiscal damage. This shouldn’t be too surprising – more job losses, less revenue, higher government spending, less demand, etc. etc.

I’m not going to argue some iron law of economics; each economy has to be examined within its own dynamic. Such a pattern, however, demands further exploration of the relationship between maintaining jobs and maintaining fiscal integrity.

But we don’t get this. All we get is Pat McArdle’s analysis in the Irish Times. He writes:

‘ . . . several euro states tried the fiscal expansion route but saw little return for their money. . . ‘.

Oh.

Germany pumped in the equivalent of 3 percent of GDP; Austria: 1.1 percent, Belgium: 1.6 percent; France: 0.6 percent; Netherlands: 1.5 percent; Sweden: 2.8 percent. All these countries were more successful in containing employment and their balance sheets. Even the UK (with all its structural problems arising from the dominance of financial capital) – they pumped in 1.4 percent, stemmed the rise in unemployment, and kept the deficit well below Ireland’s slide (if we had the same ‘little return’ as the UK, our deficit next year would be -7.1 percent, rather than the EU’s projected -12.2 percent.

Instead, Ireland took out (not pumped in) 4 percent of GDP in ‘fiscal rectitude' measures. Our GNP will fall by 17 percent – the Eurozone average will fall by 2 percent. Irish consumer spending will fall by 10 times the Eurozone rate; employment will fall by five times the rate; investment will fall off the charts and return to 1999 levels. And the deficit and debt is growing at much faster rates than the Eurozone. This is ‘fiscal rectitude’? This is success?

I have just one question for Pat McArdle and the rest of the deflationary brigade.

What economic planet do you live on?

Leave a reply to Michael Taft Cancel reply