We are not Spain, we are not Italy, we are not Portugal. Repeat. We are not Spain, we are not Italy, we are not Portugal.

We are not Spain, we are not Italy, we are not Portugal. Repeat. We are not Spain, we are not Italy, we are not Portugal.

In one sense, that’s correct. In terms of the ‘market’ view of the Irish economy, we’re worse. But don’t expect commentators who have been demanding public spending cuts to point this out; it would undermine their arguments.

Remember at the start of the recession when we were given crash tutorials in the 10-year German Bond spreads? This compares the cost of borrowing with that of prudent Germany. This was the leading index to divine what the markets thought of Government debt and, so, the Irish economy:

- The smaller the spread, the more markets are pleased.

- The larger the spread, the more markets are angry.

The 10-year bond spread was presented as the ultimate portal into the collective mind of the market.

During the Euro crisis, when bond yields were soaring, we were told we were not like the other periphery countries. Our deflationary interventions in 2009 – when billions were ripped out of the economy through spending cuts and tax increases on low-average income earners – had ‘pleased’ the markets. Therefore, while the debt of other countries were under attack, ours was safe.

To make this argument work, though, you have to ignore the 10-year bond spread – the very index that was used to justify deflationary policies in the first place.

Why is this crucial index now being ignored? Because after all the deflationary measures Fianna Fail imposed, the markets still tore strips off Government debt in the recent crisis. It’s not just that the markets were not pleased; if anything, they were even angrier. Those who demanded deflation don’t want you to know that. Therefore, don’t present the data and hope that people won’t notice.

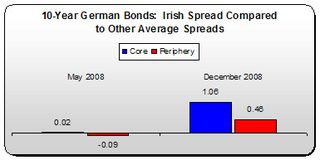

Let’s correct this. I have taken, from the Financial Times Bond Index, the average spreads of both the periphery countries (Spain, Italy and Portugal) and the ‘core’, or non-periphery countries (all other countries in the EU-15) and compared them with Ireland. I have excluded Greece since they are not in the market anymore. Let’s see what we find.

First Phase – Entering the Recession

In spring 2008, all countries were bunched together, quite close to German rates. Irish borrowing costs (as measured by the spread) were pretty much the same, on average, as other ‘core’ countries and

below the costs of the periphery countries – namely, Spain, Italy and Portugal. No crisis there. However, in a few months, gaps were emerging.

below the costs of the periphery countries – namely, Spain, Italy and Portugal. No crisis there. However, in a few months, gaps were emerging.

By the end of the year – following the bank guarantee and a panic budget which showed the Government didn’t know what it was doing – borrowing costs were substantially higher than the core countries and higher than even the periphery countries. The markets were getting angry.

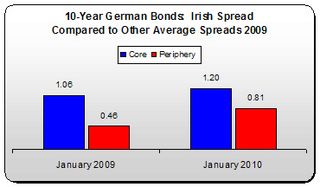

Second Phase – the Year of Deflation

Based on these gruesome numbers, the campaign for ‘decisive, courageous action’ (i.e. cut wages, cut welfare, cut services and hit low-average income earners with tax) gathered steam. This ‘tough’ action

would please the markets and bring our spreads back into line we were told. So what happened?

would please the markets and bring our spreads back into line we were told. So what happened?

Our spreads worsened. They fell even further behind ‘core’ borrowing costs. And they nearly doubled over the periphery countries.

This wasn’t supposed to happen. Our tough action – in contrast to those fiscally profligate countries on the periphery – was supposed to be rewarded by the markets. It wasn’t. Imagine that.

Third Phase – the recent Euro Crisis

In the third week in April of this year, everything started going south. The bail-out of the reckless lending by German and French banks (sorry, the Greek bail-out), the falling Euro, worries over public and private debt – markets were in turmoil; both angry and confused.

Of course, some countries, namely the ‘core’ countries weathered the storm okay; actually, better than okay. Investors sought the safety of the countries whose borrowing costs in most cases actually declined. It was the periphery countries that were next for the chopping block. So, given that the markets were ‘pleased’ (according to commentators who find it difficult to read indexes) with what Ireland had done over the previous year, how did we fare against the periphery countries which the markets were angry at?

Not good. While Portugal came under particular pressure, all the other countries remained well below Irish borrowing costs. Of the four periphery countries, Irish debt came off second worst.

And here’s the shocker. Which country now has the worst spread in the EU-14 (given that Greece is no longer a player)? Ireland. As of Friday, after a week of bounce-back, Irish spreads were higher than Spain and Italy (by a considerable amount) and marginally ahead of even Portugal.

* * *

One could despair of this debate with unsubstantiated assertions, selective use of data, spin, and gullible commentators who repeat the spin for want of a little research. Jimmy Stewart did warn us:

‘This is why financial markets were not 'reassured'. For all the Thatcherite bluster of the bond analysts, who are salesmen, bond investors understand whether they are more, or less, likely to be repaid. Reducing incomes while increasing debts only raises the risk of default, hence yields continue to rise. A crucial, but widely ignored point from S&P when downgrading Greek and Portuguese debt, is that the austerity measures have depressed activity and tax revenues. The slash & burn approach has only made matters worse.’

Too many of our commentators listen to ‘salesmen’ and pay too little attention to what is actually happening in the markets. This is not an argument that we should become slaves to every blip on a graph. As Nat O’Connor points out:

‘ . . why are the markets being treated as a singular entity with consciousness, rather than the aggregate of diverse individual and corporate investors? It would be much more accurate to report which investors are expressing concern or fear, and on what basis.’

But what this does show up is the degraded state of not only the Irish debate but of the presentation of relevant facts – facts that get pushed under the carpet because it might force the current consensus to explain itself. For deflation hasn’t worked, spending cuts haven’t worked, sitting idly by while employment has collapsed hasn’t worked.

Yes, Ireland is not like Spain or Portugal or Italy. We're worse.

Leave a reply to Aidan R Cancel reply