What kind of recession are we having – or rather, how is it impacting on different sectors of the labour force? Some time ago we heard talk of a middle-class recession – how particular ‘middle class’ occupations were being badly affected. Architects were one such profession and clearly there’s not much use for this group of people if buildings are not being built. But as the recession winds down it is clear this cannot be considered a ‘middle class’ recession.

In truth, we should be a bit wary of using this term as it is likely to add more confusion than light. It opens up questions of ‘class’ and relations in the production process – important questions. Unfortunately the CSO only provides a few labour force categories from which to work with. In so doing, we have to use broad brushstrokes.

The CSO’s Quarterly National Household Survey(QNHS) for the 2nd quarter gives breakdowns that are useful and if they can’t be necessarily equated to ‘class’, they can be equated to income and greater control of working conditions. For instance, a professional is likely to earn considerably more than a sales worker or a plant operative. Similarly, a manager is likely to have more control (though by no means total control) over their working and employment conditions than someone on the factor floor. So let’s examine two categories and find out who’s suffering the most (this builds upon Sean O'Riain's survey of the first quarter results).

Employment by Occupational Status

From the table below it can be seen that managerial and professional groups have experienced the least decline in employment while traditional ‘working class’ occupations – craft and plant operatives have suffered the most.

- The managerial / professional classes saw their employment levels fall by less than 2 percent

- The combined craft / plant operatives sectors experienced a decline of nearly 23 percent

Of course, a considerable number of craft workers would have been working in the construction sector. But plant operatives also experienced a high level of decline as well. As well, the ‘Others’ sector tend to be made up of service workers that don’t fit into the above categories (e.g. hotel and restaurant, cleaners, etc.). They are the lowest earning of all the categories and experienced an above average decline as well.

No doubt, there are certain managerial and professional categories that are suffering – such as the aforementioned architects and other property-related professions. Still, taken as a whole, it is the lower-paid manual occupations that are taking the worst hit.

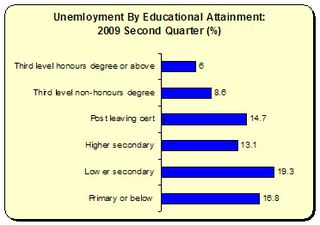

Employment by Educational Attainment

Again, though we can’t automatically assume educational attainment is directly associated with class, there is correlation between educational levels, skill sets, profession and earnings. In this respect, we find those with the least educational attainment having suffering the most from unemployment.

Those with third level honours experience a substantially lower unemployment rate than those with low educational attainment. This, though, doesn’t tell the full story. The overall participation rate stands at 71.3 percent (per Table 23A), rising to 89 percent for those with third level honours. However, among primary and lower secondary, the participation rate stands at 41.1 percent and 54.8 percent. This is compounded by the fact that one-in-six students still leave school without a Leaving Certificate qualification.

While this should not be all that surprising it, along with the above finding, raises important questions regarding the labour market and job creation going forward out of the recession. With some commentators predicting an early exit from the recession (as early as the first quarter of next year), there will be a growing emphasis on up-skilling and moving up the value-added chain with knowledge and skill-intensive employment, especially as internationally tradable services will play an increasing in Irish and world trade. As a consequence, we will find manual manufacturing work to play less significance (at least as a proportion of the workforce) and where employment does increase it will, again, rely on high-skill work.

Unless substantial intervention is undertaken – in education and (re)training, combined with job creation measures that don’t necessarily rely on the private market – we may be facing into a perverse apartheid at work in the labour market, where those with less skills and educational attainment will suffer a lifetime of low living standards. This in turn will continue to be a drag on economic growth going forward and undermine our attempts to maximise the economic and social benefits coming out of the recession.

In other words, we may be facing a return to the same ol' equation – squared.

Leave a reply to Barry Cancel reply