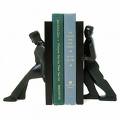

The Government now has its bookends. On the expenditure side, the McCarthy Report; on the taxation side, the Commission Report. Now we can stack the economy between the two and . . . squeeze. The only problem is that one of the bookends may not be so reliable. Indeed, it may fall off the bookshelf. And if that were to happen, the other bookend may find its function redundant.

The Government now has its bookends. On the expenditure side, the McCarthy Report; on the taxation side, the Commission Report. Now we can stack the economy between the two and . . . squeeze. The only problem is that one of the bookends may not be so reliable. Indeed, it may fall off the bookshelf. And if that were to happen, the other bookend may find its function redundant.

The Commission Report is the dodgy endpiece. The Report is at great pains to highlight its remit, notably that its recommendations must be placed in the context of continuing Ireland’s low-tax model. But sometimes it doesn’t sound too excited by this:

‘In keeping with our Terms of Reference these recommendations have regard to the medium to longer term and, in aggregate, they are compatible with keeping Ireland a low tax economy.’

Compatible, yes. Inevitably so? That is more problematic. The Report protests that its recommendations would be ‘revenue-neutral’ – Peter and Paul would balance out. Except that, while we get a lot of proposals to raise money, there isn’t a comprehensive schedule of tax cuts to balance. They’ve left that exercise, by and large, to the Government. If I were a Minister, I wouldn’t be thanking the Commission.

All this suggests that reading the Commission report is a more nuanced affair than the McCarthy Report which was just a blunt instrument to hammer, for the most part, low and average income earners by cutting social transfers. The McCarthy Report is bad melodrama, the Commission report approximates a more confusing film noir.

Our starting point is to separate out the political context from the actual content. SIPTU Vice-President Brendan Hayes has done the public debate an enormous service by refusing to sign the report. His letter which appears in the Appendix lays out the primary reason:

‘The Commission’s Recommendations reinforce a low-tax model of the economy and of society that I do not support.’

All his other objections flow from this fundamental premise. By highlighting this, Brendan goes to the heart of the matter and elevates the ‘politics’ of the report in a way that makes clear the real and substantial difference between a progressive and a conservative economics (his interview on Morning Ireland is worth listening to for an elaboration on his letter). Paul Sweeney also makes useful points in this regard over at Progressive-Economy. This is where the battle lies.

But encouragingly, in fighting this battle, we can turn much of the content of the Report against this political context and, in many cases, against the regressive recommendations in the Report itself. Let’s take one example: tax expenditures.

The section on tax expenditures is by far the largest section in the Report and arguably the most detailed in terms of highlighting revenue and costs. There is much progressive meat here. The Report acknowledges the regressive impact of much tax expenditure – in addition to their inefficiency, deadweight, lack of cost control and lack of transparency. For instance, 50 percent of the revenue foregone under mortgage interest relief, which costs the Exchequer over €700 million, goes to the top two income deciles. There is considerable revenue gain to be made through the reform of tax expenditures with less deflationary impact and much benefit to both equity and the Exchequer.

The Report lists 96 tax expenditures, not including personal credits. This is by no means an exhaustive list – it omits discussion on 17 property-related schemes, though some of these are being phased out (the Labour Party has estimated that these property-related schemes still cost the Exchequer over €500 million).

Of these 96 tax expenditure programmes, 29 could not be costed. However, of those that could, the revenue foregone amounted to nearly €11 billion. That’s equivalent to all the revenue obtained in the income tax system and a third of all tax revenue. The Report breaks down these tax expenditures into two three categories:

- those they would continue as is: these cost €4 billion (though over half of this come from one tax relief – the exemption of the sale principal private houses from capital gains tax)

- those they would discontinue: this would save over €700 million,(more than half of this, though, comes from the controversial taxation of Child Benefit), and

- those they would reform in some way: these cost over €6 billion.

Let’s examine one small area in housing tax expenditures: namely the operation of mortgage interest (MIR) and rent relief. The starting point is the Report’s general recommendation regarding tax expenditures:

‘We have concluded that, in general, direct Exchequer expenditure should be used instead of tax expenditures. This allows greater transparency and control of public resources and avoids many of the aforementioned undesirable characteristics.’

This is a correct and progressive perspective. Unfortunately, the Report didn’t apply this principle to housing tax reliefs. Instead, they propose that:

- MIR be confined to first-time buyers only, and

- Rent relief be abolished

While the first is fair enough, removing rent relief will disproportionately affect those on lower incomes (tenants are generally poorer than owner-occupiers) while creating an imbalance between the home-owning and rental sector. There is another way, however, using the Report’s general recommendation. If the MIR and rent relief were wrapped up into a taxable Housing Benefit, this could reduce the cost of these housing supports, progressively direct the subsidies to low and average income groups while achieving considerable social welfare savings.

For instance, the average cash subsidy to those in receipt of MIR and rent recipient is €840 annually, at a cost of over €840 million per year. Setting the new Housing Benefit at a level substantially higher than the average cash subsidy, and taxing it, would still reduce the overall costs (especially if second-house purchasers were excluded).

As well, this would reduce the social welfare costs of rent and mortgage interest supplements as home-owners and tenants would keep the Housing Benefit whether employed or not. This Benefit would be subtracted from the social welfare subsidies.

We could go further and extend the Housing Benefit to all first-time buyers and tenants – public and private. This would have progressive knock-on effects for local authority tenants – comprising some of the lowest income groups in society – while at the same time allowing local authorities to readjust the differential rent scheme to recoup more of their construction and maintenance costs. Tenant and public landlord would both gain.

This is one small example of how the Report’s recommendations can be transformed in a progressive manner. That doesn’t take away from the larger political context – the low-tax model it espouses and which is a direct contributor to the economic and fiscal crisis we find ourselves in. But disentangling the context from the content frees us up to be more creative. I’ll return to other aspects of the Report in subsequent posts.

For at the end of the day, progressives are going to have to write their own Taxation Report – one which shows how we can increase taxation to facilitate economic growth and social infrastructure development, consistent with the economy’s ability to absorb such tax increases.

We can turn the Commission on Taxation against the Right and even against their Report’s own regressive recommendations.

And in so doing, remove one of the bookends that threaten to squeeze the economy.

Leave a comment