The Commission on Taxation is about to descend upon us – six hundred pages worth, apparently. The Commission report is of a different order than the McCarthy report. The latter was set up to find ‘savings’ in order to reduce the high borrowing requirement (it failed to do this as we discussed previously – the level of savings is highly inflated). This is not the Commission’s remit. It was set-up to review taxation issues in the context of maintaining a low tax regime – not discover new sources in pursuit of increasing revenue in order to reduce the borrowing requirement. Therefore, the two reports are not comparable.

The Commission on Taxation is about to descend upon us – six hundred pages worth, apparently. The Commission report is of a different order than the McCarthy report. The latter was set up to find ‘savings’ in order to reduce the high borrowing requirement (it failed to do this as we discussed previously – the level of savings is highly inflated). This is not the Commission’s remit. It was set-up to review taxation issues in the context of maintaining a low tax regime – not discover new sources in pursuit of increasing revenue in order to reduce the borrowing requirement. Therefore, the two reports are not comparable.

And if the limited remit wasn’t sufficient (though it was enough to ensure that one Commission member – SIPTU’s Brendan Hayes – has refused to sign on), we have Minister Lenihan claiming that tax is high enough. In terms of dealing with the fiscal deficit, he won’t be looking to increase revenue. He’s got his sights firmly on public expenditure – in effect, social welfare, health, education and public sector wages/employment.

Let’s examine two aspects of this argument. First, is the Irish economy taxed too much? From a comparative perspective, this argument that can hardly be sustained.

- In 2007, the average level of taxation (as a % of GDP) in the other EU-15 countries was 46.7 percent.

- Compare that to Ireland’s 40.6 percent (using GNP).

We ranked rock bottom. We would have had to increase tax revenue by €9.2 billion just to reach the average.

The EU Commission predicts this situation will pertain up to 2010. They project that Irish tax revenue will fall to 38 percent of GNP, a result of the collapse of tax revenue arising from the loss of economic activity combined with the structural deficit. The other EU-15 countries will also experience a slight drop but less than Ireland, owing to the fact that unemployment has not risen to the same extent as here. S

o, on just an international comparison, it can hardly be suggested that we have hit a ceiling – unless we intend to live in a very small house in the future.

However, there is an argument that increasing taxation – especially general taxes on low and average income groups – is not a wise course during an economic contraction. It is deflationary, resulting in reduced domestic demand with all that consequences that entails (e.g. higher unemployment, reduced enterprise activity, etc.). This argument is jumped on by the Right to argue for prioritising public expenditure cuts, without likewise conceding that such cuts are deflationary, too.

That’s why a viable alternative is to dispense with overall public expenditure cuts and general tax increases (this doesn’t exclude minimally deflationary measures – cutting ‘real waste’ or increasing taxes on high income/wealth), and instead engage in sustained investment stimulus to increase economic activity and reduce unemployment.

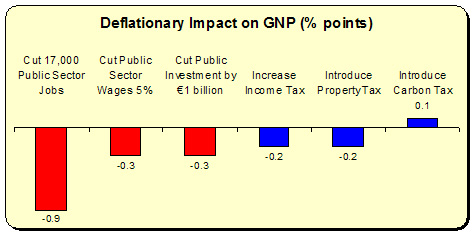

Even so, looking forward when the economy has moved from recession to recovery – where does the most economically efficient and fiscally beneficial balance lie between cuts and taxes? I’ve referred in the past to the ESRI’s simulation of budgetary proposals, mostly focusing on public expenditure cuts. But they also ran a number of simulations on tax increases such as property tax, income tax and carbon tax. Let’s compare these with public expenditure cuts, to see what would be the better course to take to engage in fiscal consolidation. It should be noted that the ESRI set up similar ‘shock’ magnitudes. Each of these proposals are designed to either reduce expenditure or raise taxation by €1 billion. So we are comparing like-with-like.

First, the deflationary shock to the economy. It can be seen that tax increases have a less deflationary effect – at least, during an economic contraction.

The worse option – in terms of prolonging and deepening the recession – is to cut public sector jobs. However, all tax increase measures have a less deflationary impact than any spending cut – even public investment cuts (which is actually a cut for the future). Indeed, the introduction of a carbon tax of €34 per tonne would actually see GNP rise marginally though this wouldn’t come without a cost (the ESRI predicts a loss of competitiveness and a decline in output as a result).

The worse option – in terms of prolonging and deepening the recession – is to cut public sector jobs. However, all tax increase measures have a less deflationary impact than any spending cut – even public investment cuts (which is actually a cut for the future). Indeed, the introduction of a carbon tax of €34 per tonne would actually see GNP rise marginally though this wouldn’t come without a cost (the ESRI predicts a loss of competitiveness and a decline in output as a result).

So which options would be the most fiscally beneficial? Don’t forget, each proposal is designed to ‘save’ the Exchequer €1 billion in gross terms but that’s before a full impact assessment has been performed. The ESRI calculates the net savings arising from their assessment.

As can be seen, tax increases have a higher return to the Exchequer than public expenditure cuts. The worst option is cutting public sector jobs – from a headline €1 billion reduction, the net savings to the Exchequer is only €490 million whereas carbon tax returns a net savings of €900 million.

As can be seen, tax increases have a higher return to the Exchequer than public expenditure cuts. The worst option is cutting public sector jobs – from a headline €1 billion reduction, the net savings to the Exchequer is only €490 million whereas carbon tax returns a net savings of €900 million.

Of course, more detailed investigation would need to be conducted to more fully assess the impact. For instance, a carbon tax without relief for low income groups could turn more deflationary and result in reduced net savings if it was disproportionately regressive. Similarly with property tax.

But what this does do is give us useful parameters within which to work. For instance, the foundations of a property tax could be established immediately with rates on only the highest income groups at work. As the economy recovers and is in a stronger position to absorb the fiscal shocks, then the tax could be extended to all households. This approach – aligning the introduction of tax increases with the economy’s capacity to absorb such increases – could ensure sustainability without risking torpedoing a fragile recovery.

This, of course, would require a government that is sensitive to the capacity and potential of the economy in both the short and long-term. We don’t have such a government. There is little inkling of such sensitivity from any alternative government led by Fine Gael. Indeed, this sensitivity is lacking in the national debate. All we get is ‘cuts good, taxes bad’.

That type of antediluvian discourse is hardly amenable to nuance.

Leave a reply to D_D Cancel reply