‘However, given the enormous scale of the problem, it would be fanciful to suppose that it can be solved without at least some reductions in public spending, and anyone who doubts this cannot really be regarded as a serious participant in the public discourse on the matter.’

‘However, given the enormous scale of the problem, it would be fanciful to suppose that it can be solved without at least some reductions in public spending, and anyone who doubts this cannot really be regarded as a serious participant in the public discourse on the matter.’

Well, that put us in our place. Not only are public expenditure cuts so self-evident, beyond the need for any debate; anyone who argues otherwise is, ipso facto, not serious. Therefore, there is no need to debate with them. What a convenient world– yes, we’ll have a debate; but we don’t have to debate with anyone who disagrees with us because, by reason of the fact they disagree with us, they are not worthy to participate in the debate.

Jim O’Leary, the author of this ‘non-debate debate’, is a serious contributor to the . . . well, debate. His arguments are worthy of being read and discussed in detail. So, I’m going to do just that. Admittedly, I along with many others won’t be allowed to discuss this at the table – we are not worthy. We won’t even be allowed to discuss it through the keyhole. We will have to stand outside the house, in the cold and the rain and the dark. We will struggle to be heard.

Jim presents two ‘necessary’ measures. The first set is intended to:

‘ . . . reduce the yawning gap between Government spending and receipts (cuts in public services, social welfare and public sector pay) . . this is not discretionary, but an imperative, namely the reduction in the huge budget deficit.’

Note the clever sleight-of-hand here. No one disputes the imperative of reducing the fiscal deficit. But Jim takes primarily one means to this end – cuts – and transforms it into an end in itself. So intertiwned are the two – cuts and fiscal consolidation – that to question the efficacy of the former is to question the need for the later.

Yet, there is a data to suggest that not only will cutting public spending fail; indeed, it is failing before our eyes. I won’t rely on the generalised (and according to Jim, ‘naïve’) argument that cutting Government consumption and investment during the middle of an out-of-control economic contraction will only make things worse. Let’s go back – one more time – to the ESRI simulations. Take two proposals: cut 17,000 public sector jobs and cut public sector wages by 5%. What is the result?

- GNP: -1.2 percent

- Consumer Spending: -1.3 percent

- Unemployment: + 1 percent

So, we prolong the recession, reduce domestic demand (that will do wonders for business turnover) and throw another 20,000 people on to the dole. But what will it do it for that yawning gap that Jim refers to? It would bring down the fiscal deficit this year from -12.2 percent (using the ESRI estimate) to -11.6 percent.

Wow! Slashing public sector employment and wages will close the ‘yawning gap’ by 0.6 percentage points. And what do we have left? A ‘yawning gap’. But now we have a weaker economy (reduced GNP, more unemployment, diminished consumer spending), less able to generate the activity needed to take action on the debt down the line. Cutting public expenditure provides the facade of fiscal consolidation but that's all.

This same façade is at work in Jim’s second set of measures – an expansionary fiscal contraction that will facilitate a reduction in wages which will, in turn, increase our competitiveness. I’ve covered this subject before – how a wage reduction of 5% in the manufacturing sector would result in a reduction of 0.4 percent in enterprise costs which would in turn mean that an enterprise could, therefore, cut the cost of a €100 product by 30 cents. Would 30 cents really make a difference to our competitiveness? Maybe it would – but it is, at least, debatable, contestable, worthy of further discussion.

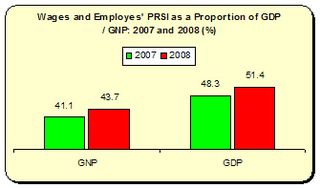

But Jim pulls out another figure – how wages and salaries make up 60% of our GDP. He calls this ‘an eloquent statistic’. That may be the case, but I can’t find where this eloquence is expressed. The CSO’s National Income and Expenditure shows that wages and salaries make up nowhere near 60% of GDP, or GNP, not even when you combine wages and employers’ PRSI (a common measurement). At most, the very most, it comes to 51%. And if you think that the increase in the wages’ share in 2008 is evidence that workers’ are taking ‘advantage of the recession’ to increase their income, consider this.

But Jim pulls out another figure – how wages and salaries make up 60% of our GDP. He calls this ‘an eloquent statistic’. That may be the case, but I can’t find where this eloquence is expressed. The CSO’s National Income and Expenditure shows that wages and salaries make up nowhere near 60% of GDP, or GNP, not even when you combine wages and employers’ PRSI (a common measurement). At most, the very most, it comes to 51%. And if you think that the increase in the wages’ share in 2008 is evidence that workers’ are taking ‘advantage of the recession’ to increase their income, consider this.

Between in 2002 and 2007 gross wage and salaries increased by over 10 percent per anum (that’s the gross amount of wages in the economy, not individual wage levels). Between 2007 and 2008, wages and salaries increased by less than 2 percent – reflecting the massive job losses. The reason the wages share increased in 2008 can be put down to a shrinking economy.

Still, does Jim have a point – that Irish wages, as a proportion of economic output, have risen too much too fast? On the eve of the Celtic Tiger Boom in 1995 – Irish wages (including Employers PRSI) made up 51 percent of GNP – compared to 48.3 percent in the year before the recession kicked in. If anything, even after all that job creation and wage increases, the wage share decreased.

Jim outlines the areas that are permitted to be debated:

‘There is room for argument about the pace at which this reduction should occur. There is also room for debating the composition of that adjustment as between spending cuts and tax increases.’

Now, since the level of public expenditure is not allowed to be debated, I’m hoping Jim will allow another area to be considered. Why is the Government currently missing its fiscal target? Let’s recap.

In October, Fianna Fail brought in an income levy in order to keep the deficit at -6.5 percent. They brought in public sector wage cuts in February to keep the deficit at -9.5 percent. Then they brought in the April budget – more cuts, more levies – to keep the deficit at -10.7 percent. This was supposed to be the last chance saloon, our last opportunity before the international markets got radical on our fiscal backsides.

So how’s the latest new line holding up? The ESRI says the Government will fail again, that the deficit will rise to 12.2 percent. The IMF, the OECD, and the EU Commission project similar deterioration. And next year? The Government intends to go through another round of spending cuts and tax increases. Well, we certainly know they can’t hold the line at 10.7 percent – that’s already blown out of the water. And along comes the EU Commission, projecting that the deficit will spin out of control at nearly 16 percent.

None of this gets much mention – how pursuing deflationary budgetary strategies during a recession is like running in quicksand; you burn up a lot of energy, weaken the body – but still end up sinking.

And you’re not likely to hear much mention. Because there is a danger that it might lead us to the forbidden zone of economic discourse – that, maybe, maybe, there really is an alternative to the current policies of cutting public expenditure.

But we'll never know. Because one position – a position consistent with mainstream thinking in other modern economies – is deemed a priori ‘not serious’ and, therefore, unworthy of discussion. To put it another way (as a friend did to me this morning), it’s as if it was said:

‘. . . given the enormous scale of the problem, it would be fanciful to suppose that it can be solved without at least some stimulus measures, and anyone who doubts this cannot really be regarded as a serious participant in the public discourse on the matter.'

Now that would be really mean.

Leave a reply to Graham Cancel reply