Over at Dublin Opinion, Conor McCabe is continuing his excellent analysis of contemporary class relations, this time using the CSO’s new National Employment Survey for 2007. He challenges the sloppy thinking that suggests we have a ‘middle-class’ majority, concluding that nearly two-thirds work in what can be properly called ‘working class’ occupations:

Over at Dublin Opinion, Conor McCabe is continuing his excellent analysis of contemporary class relations, this time using the CSO’s new National Employment Survey for 2007. He challenges the sloppy thinking that suggests we have a ‘middle-class’ majority, concluding that nearly two-thirds work in what can be properly called ‘working class’ occupations:

‘From the viewpoint of wages, or occupation, or employment status, or education, we’re constantly coming up with the majority of the population in working class jobs, with working class levels of pay. The middle class majority is a middle class myth.’

Prior to the last general election we were weighed down with simplistic analysis: ‘we’re all middle class’, ‘the aspiring middle class’, and such. We don’t hear these terms being bandied about much anymore. But, then, recessions have a tendency to cut through froth just as they cut through livelihoods.

I want to take a different a different route that nonetheless leads to a similar conclusion. Conor rightly warns us

‘Income is not a determinator of class, and to think of class in such terms is to miss the point that class is a social relation, not a category . . . there are enough commentators . . . who are all too willing to see class purely in terms of income, who maintain that Ireland has a majority middle class, with a working class rump and a lucky few at the top. And they cite Ireland’s wage levels as perfect proof of the middle class majority.’

Bearing this in mind, let’s play a little game. Let’s assume that ‘middle income’ can describe that large grouping between the lowest and highest income groups. Let’s adopt the mistake that many make – to assume that this middle stratum is the amorphous ‘middle class’. For I want to show how little this ‘middle grouping’ makes; and, further, that without the welfare state this middle grouping would be even more impoverished. This will hopefully complement Conor’s work as we head into discussion of pay freezes and social welfare cuts.

The EU’s Survey of Income and Living Conditionsprovides useful decile breakdowns of income from a variety of sources. Our first stop is the household deciles, but we should treat this with caution. Households in the higher deciles have more people working than those in the lower income deciles. Still, what does it tell us?

The top one-in-five households ‘earn’ (income from employment, self-employment and from capital) a lot more than the average middle strata, never mind the lower strata where there would be a disproportionate number of elderly and unemployed living alone. On average, the upper strata earn 3.5 times what the middle strata earn. The range of middle incomes stretches from €114 per week in the third decile to €1,236 in the eighth decile. Yes, the top twenty percent of households contain 37 percent of all those at work. However, households in the middle 60 percent strata contain 60 percent of all those at work.

The top one-in-five households ‘earn’ (income from employment, self-employment and from capital) a lot more than the average middle strata, never mind the lower strata where there would be a disproportionate number of elderly and unemployed living alone. On average, the upper strata earn 3.5 times what the middle strata earn. The range of middle incomes stretches from €114 per week in the third decile to €1,236 in the eighth decile. Yes, the top twenty percent of households contain 37 percent of all those at work. However, households in the middle 60 percent strata contain 60 percent of all those at work.

The CSO attempts to even out the demographic factors by use of net equivalised incomes. While this is an artificial measurement, it helps us plot the comparative earnings per strata. As we can see, the top 20 percent income earners make nearly three times the average of the middle strata.

The CSO attempts to even out the demographic factors by use of net equivalised incomes. While this is an artificial measurement, it helps us plot the comparative earnings per strata. As we can see, the top 20 percent income earners make nearly three times the average of the middle strata.

It must be stressed that both these measurements are abstractions but what is noteworthy in both of them is how much more those in the top deciles earn than those in the great middle. And how little those in the great middle earn over those in the lowly lowers.

So how are the majority of household’s incomes sustained if earnings from work are so low? Quite simply, through the welfare state. On average, social transfers (Child Benefit, pensions, social welfare payments, etc.) make up a quarter of households’ incomes. At the lowest income levels, social transfers make up 93 percent of total net income. But even in the upper middle strata, the reliance on social transfers is not inconsiderable. These are the same transfers that commentators are demanding be cut – cuts that will have a severe, almost devastating, effect on those on the lowest incomes.

So how are the majority of household’s incomes sustained if earnings from work are so low? Quite simply, through the welfare state. On average, social transfers (Child Benefit, pensions, social welfare payments, etc.) make up a quarter of households’ incomes. At the lowest income levels, social transfers make up 93 percent of total net income. But even in the upper middle strata, the reliance on social transfers is not inconsiderable. These are the same transfers that commentators are demanding be cut – cuts that will have a severe, almost devastating, effect on those on the lowest incomes.

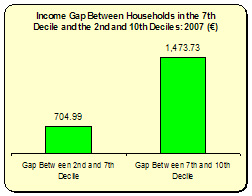

Where does all this lead us in practical political terms? That even at higher levels of the middle strata, households are closer to lower income groups than they are to the highest decile group. Households in the 7th highest decile – with more people at work – are twice as close in money terms to the 2nd decile as they are to the top earners. Whatever about the penthouse being not that far from the basement, clearly the case the basement and the middling sitting room are located on the same street.

Conor states that the ‘middle class majority is middle class myth’. Absolutely. And when we look at income deciles, we discover where this myth melts away. For the great middle strata are a long ways from mythical middle class bank accounts, reliant on social transfers, closer to the basement than to the penthouse and balancing on ever more precarious income streams.

Conor states that the ‘middle class majority is middle class myth’. Absolutely. And when we look at income deciles, we discover where this myth melts away. For the great middle strata are a long ways from mythical middle class bank accounts, reliant on social transfers, closer to the basement than to the penthouse and balancing on ever more precarious income streams.

Surely, there is a progressive politics in here somewhere.

Leave a comment