History is such a malleable thing. It can be twisted this way and that to support or oppose any contemporary position. Take An Bord Snip Nua – this is a grand thing altogether. How do we know this? Because, sure, its predecessor was such an outstanding success. Yes, it brought pain but it set the groundwork for the Celtic Tiger economy. So goes the history; if we gird our loins, cut and hack away, we too can replicate this outstanding success. Suffer a couple of years of fiscal pain, and economic paradise awaits.

History is such a malleable thing. It can be twisted this way and that to support or oppose any contemporary position. Take An Bord Snip Nua – this is a grand thing altogether. How do we know this? Because, sure, its predecessor was such an outstanding success. Yes, it brought pain but it set the groundwork for the Celtic Tiger economy. So goes the history; if we gird our loins, cut and hack away, we too can replicate this outstanding success. Suffer a couple of years of fiscal pain, and economic paradise awaits.

But history is not so straight-forward and certainly not so reductionist. Was it really the case that the ‘cutbacks’ endured under Mac the Knife (Finance Minister Ray McSharry) were (a) successful and (b) set the preconditions for the growth explosion in the mid-1990s? Let’s take a look at some provocative facts for clearly there is a lot of myth making about that period – a period that ran from 1987 to 1989, encompassing three budgets.

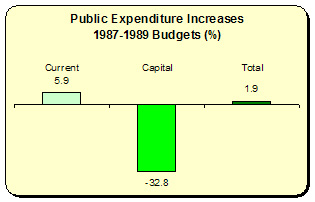

First, how much was cut? In nominal terms, public expenditure wasn’t cut – it increased. During the three budgets, total expenditure increased. Current expenditure increased. Even excluding interest payments, current expenditure increased by over 5 percent. The main target of the knife was that ol’ standby – capital expenditure. Cutting investment is the easiest option. It doesn’t take away from what people already have – it only defers something we don’t have. This started a period of long-term chronic under-investment in our economic base.

First, how much was cut? In nominal terms, public expenditure wasn’t cut – it increased. During the three budgets, total expenditure increased. Current expenditure increased. Even excluding interest payments, current expenditure increased by over 5 percent. The main target of the knife was that ol’ standby – capital expenditure. Cutting investment is the easiest option. It doesn’t take away from what people already have – it only defers something we don’t have. This started a period of long-term chronic under-investment in our economic base.

But that’s only Irish public expenditure. Don’t forget – this was ‘begging bowl’ days, when Ireland was one of the poorer performing economies in the EU. So what about public expenditure in Ireland? Between 1987 and 1989 we received over £1 billion under the EU Social and Regional Development Funds – a substantial 38 percent increase in the previous three years under the hapless Fine Gael/Labour government. Now, £1 billion might not sound much but were we to receive the same proportional amount it would come to nearly €6 billion over the next three years. That would subsidise a lot of cuts, but it’s doubtful if the EU today would play ball.

Second, there is much talk about how the minority Fianna Fail government brought down the public spending/GNP ratio. In 1986 public expenditure amounted to 54.7 percent of GNP (if you think that’s because we had some kind of super-Nordic government, remember – it was largely due to interest payments and social welfare). By 1989, spending was brought down to 45.1 percent. But this was only the continuation of a trend that was already in place since 1983 when expenditure was over 62 percent of GNP.

But there was one thing that saved Fianna Fail’s bacon. The numbers on the Live Register started to fall. Was that because all this fiscal contraction started producing jobs? Hardly. Between 1986 and 1992, the economy was generating an average of only 14,000 new net jobs, and while unemployment didn’t rise it didn’t fall either. Between 1988 (the first year of the ILO calculation) and 1993, unemployment fell by less than 1% leaving nearly 16 percent still unemployed. So what happened here?

Yes, you guessed it: emigration. Between 1987 and 1989 over 100,000 emigrated. While not all of these would have been of working age, it’s a fair bet most were – the overwhelming majority. The numbers emigrating amounted to 8 percent of the entire labour force in 1989. To put this in perspective, we’d need over 180,000 to leave over the next three years to reach this level.

Emigrants are great. You don’t have to pay them any dole. They reduce demand on social services. They don’t end up clogging our jails. It’s a great solution, and it certainly gave the Government at the time a real dig out. Expansionary fiscal contraction? Try expansionary demographic contraction.

There is no question about the impact of some of the cuts during that period. But, as always, there were choices. Fianna Fail did choose – they chose to abolish the Land Tax – just as they abolished the Wealth Tax a decade earlier. When it came to patients being moved out of closed hospital wards or the IFA, Fianna Fail certainly knew whose side it was on.

Whatever about our ‘historians’ today, what did contemporaries think of this policy? They couldn’t ditch it fast enough. First to go was Mac the Knife himself – kicked upstairs to the EU Commission. During the 1989 election campaign – resulting from a lost vote on a non-economic private member’s bill – Charles Haughey apologised on an RTE phone-in show for not realising the damage being done to cutbacks in the health services (what’s new?). The election result put the seal on Fianna Fail’s historical anti-coalitionism, and for the first time they entered cabinet with another party – the right-wing PDs. What happened then? More of th same? Don't you believe it.

The Fianna Fail/PD government went on a spending spree. In the very first budget spending cuts were reversed – and how; public spending rose by 7 percent. In the three budgets under this government, spending increased by over a quarter while capital spending increased by a third.

The Fianna Fail/PD government went on a spending spree. In the very first budget spending cuts were reversed – and how; public spending rose by 7 percent. In the three budgets under this government, spending increased by over a quarter while capital spending increased by a third.

And then there was that EU dosh. It really started flooding in – over £2.2 billion in the three year period. This was more than double the amount received in the previous three year period. Public expenditure in Ireland leaped and bounded ever upwards.

And this was done against a pretty bleak fiscal situation. While spending was being increased, the debt/GDP ratio was over 85%, though falling; interest payments on the debt soaked up a quarter of tax revenue and over 7% of GDP (compare that to payments in 2008 which made up only 1 percent of GDP). Still, they kept spending.

And then the 1993 devaluation – which made our exports cheaper.

And then the fruits of years of work by the IDA – the multinationals swept in, bringing mega-growth.

And the direct state investment into the high-tech domestic sector.

We never hear that narrative – one that poses spending, investment and public policy as the driving force in the emerging economic boom. Rather, all we get is a selective and reductionist recitation of history, skewered to fit a set of pre-conceived policies.

And just remember, when you read reports of today’s Bord Snip proposing cuts in social welfare, that throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, social welfare increased every year. And public sector workers received pay increases.

History has much to teach us.

Leave a comment