Over at Cedar Lounge Revolution, WBS is doing a good job tracking the ongoing campaign against Ireland’s borrowing capacity and, in particular, the performance of the National Treasury Management Agency. On a recent post, I agreed but received this challenge from barratree

Over at Cedar Lounge Revolution, WBS is doing a good job tracking the ongoing campaign against Ireland’s borrowing capacity and, in particular, the performance of the National Treasury Management Agency. On a recent post, I agreed but received this challenge from barratree

Michael, – I’ve yet to see you addressing the point that most people are concerned about. Its the medium to long run ability to finance the country not right now in the present. If we undertook a massive stimulus plan in would completely undermine any trend towards a sustainable budget. After 2 years we would be looking at laying off all those people taken on by the state to build railway lines etc and there still being no jobs for them. And the deficit would be sky high. B

I accept that, in arguing for an expansionary investment approach, I might not have comprehensively addressed the issue of fiscal sustainability. However, I question whether ‘most people’are concerned about long-term budgetary issues. People I come across are more worried about losing their jobs, or getting a job, or losing their business or their pension, etc. Nonetheless, barratree has asked legitimate questions. So here goes.

We first have to acknowledge that currently there is no strategy – being pursued or articulated – capable of leading us towards a sustainable budget. The Government’s April budget was introduced for one reason and one reason only – to bring a 12 ¾ percent fiscal deficit (which they claimed was unsustainable) down to 10 ¾ percent. This was intended as one more step in bringing the deficit below – 3 percent by 2013. They had, broadly speaking, two options:

- Attack the deficit by raising taxes and cutting government consumption and investment

- Attack the deficit by increasing economic activity through investment and job creation

They chose the former; a disastrous choice. To pursue deflationary strategies in a rapidly deflating economy is to pour fuel on the flames. With consumer spending falling, with jobs being lost, with investment collapsing – the Government has done all the wrong things.

This is not some mere deduction (though history tells us that the last time Governments pursued these kind of strategies, the Great Depression resulted; which is why no other government is doing what Fianna Fail is doing, regardless of their ideological hue). In their respective projections, the ESRI and the EU Commission have given current policy a thumbs down. Remember that Government’s goal in raising taxes and cutting spending was to reduce this year’s deficit to 10 ¾ percent. What’s the verdict?

- The ESRI projects the deficit to run to 12 percent

- The EU Commission projects the deficit to go out of control: 15.5 percent

To make matters worse, the NTMA’s Michael Somers suggests that our overall debt could exceed 100 percent of GDP shortly.

So the question is not whether we should borrow more – we will, under any scenario. The key question is what do we borrow for? If we continue down the Government’s road, we will be borrowing to sustain ever higher levels of unemployment benefit, ever lower levels of tax revenue.

There is another option – to borrow for investment. I have made a number of suggestions in this regard. But what is needed is a new budgetary arithmetic based on investment. We know that the current arithmetic based on deflation will fail. Can an investment one succeed?

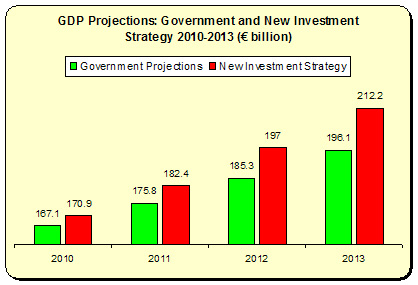

Let’s say a progressive government was determined to invest up to 3 percent of GDP annually into an economic investment programme over the next four years, or between €5 billion and €6 billion each year. If we use an extremely conservative multiplier effect – given Ireland’s open economy – we could expect the GDP to be approximately €16 billion higher than under the Government’s projections. I’ve used a 0.75 multiplier effect – the US Government uses much higher estimates, up to 1.65, but then they have a large, less open economy than we have (Fine Gael uses higher multipliers, which I am somewhat sceptical).

GDP growth is higher but it will come at a cost – an extra €21.5 billion borrowing for an investment programme over the next four years. However, the net extra borrowing will be much less because the investment programme is designed to put people back to work (that’s why President Obama, Prime Ministers Rudd and Brown, Chancellor Merkel describe their stimulus programmes in terms of jobs created/saved – not in terms of expenditure or debt). In effect, a stimulus programme widens the tax base by creating new taxpayers. Compare this to the Government’s deflationary strategy, which narrows the tax base, by letting people fall into unemployment.

GDP growth is higher but it will come at a cost – an extra €21.5 billion borrowing for an investment programme over the next four years. However, the net extra borrowing will be much less because the investment programme is designed to put people back to work (that’s why President Obama, Prime Ministers Rudd and Brown, Chancellor Merkel describe their stimulus programmes in terms of jobs created/saved – not in terms of expenditure or debt). In effect, a stimulus programme widens the tax base by creating new taxpayers. Compare this to the Government’s deflationary strategy, which narrows the tax base, by letting people fall into unemployment.

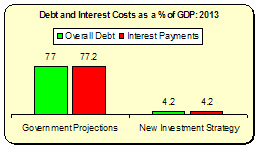

Again, let’s use the Government’s tax projections (they project tax revenue will be 21.2 percent of GDP next year, rising to 22.3 percent by 2013 – yes, they are intent on maintaining a low-tax economy). By applying these minimal percentages, we find that tax revenue under a new investment strategy increases by €8.7 billion over the four-year period. That would reduce the fiscal deficit in each year, leading to an overall net debt increase of €12.8 billion. Where would this leave us by 2013?

Pretty much in the same place as where we might be under the Government’s strategy. That’s because while the debt will rise, so will the GDP – so the proportion remains the same. Moreover, this doesn’t count the savings on social welfare expenditure – so we might expect the annual fiscal deficits and, so, the overall debt burden to be lower still.

Pretty much in the same place as where we might be under the Government’s strategy. That’s because while the debt will rise, so will the GDP – so the proportion remains the same. Moreover, this doesn’t count the savings on social welfare expenditure – so we might expect the annual fiscal deficits and, so, the overall debt burden to be lower still.

But there is one big, significant, enormous difference – under a new investment strategy, the economy will be in a stronger position to pay off its debt.

To take one example of this: employment. How many more people can we expect to be employed as a result of an investment strategy? This, of course, depends on the type of programmes pursued. For instance, there is a strong argument to postpone the North Metro; it is more capital and import intensive and less labour intensive. Instead, for the next couple of years we could expand the Government’s insulation programme; this is more labour intensive and more of the materials would be supplied by domestic enterprises. Both are necessary, but it’s about prioritising necessary investment in a more strategic way (in any event, the North Metro still has a lot of preparatory work to do before the ground is broken).

At a conservative estimate, we could expect between 15 and 25 percent of the extra stimulus to find itself into wages, depending on the labour intensity of the programmes. This would translate into between 81,000 and 134,000 average industrial wage equivalents. This corresponds to Fine Gael’s own job creation estimation (100,000 jobs arising from a €18 billion investment over four years). An economy with that many more people at work is in a much, much stronger position to absorb the debt burden than one with all those people unemployed and on the dole (less tax, more government expenditure).

In addition – and, again, this depends on focused and strategic government policy – if the investment is primarily invested into our infrastructural base, the economy will perform stronger. One example of this is a programme to roll out Next Generation Broadband. This is a necessary component of the new economy. If we have it on the other side of the recession, we will be more competitive. Seaport infrastructure, green energy, early childhood education, primary health care-team network, a proper spatial/regional strategy – if these are not in place, we will fall further behind our trading partners.

Barratree raises the issue of what happens to all those people employed as a result of the stimulus investment – will they be made redundant once the stimulus is ended? This poses a down-the-line challenge to government policy. Let’s remember – a stimulus is intended to raise the productive base to a level that it could be achieving were it not for the downturn.

For instance, the ESRI assumes higher growth rates by mid-next decade. If this is the case – because of the eventual recovery in global demand – then the trick will be to ease an economy out of stimulus and into this increased growth. Particular jobs may be lost, but the supply of jobs – as current and new enterprises increase output – will grow. Managing this rise in supply will be no easy task.

For instance, a greatly expanded insulation programme – targeting construction workers with few skills (SIPTU estimates that nearly 40 percent of such workers only have a junior certificate level of education) – would combine work with training/education opportunities for employees on the job. Hopefully, this would mean that as the insulation programme is reduced, many of the construction workers would now have marketable skills for the new jobs coming on stream.

Of course, many of the new enterprises established as part of the stimulus programme would remain in place – for the simple reason they are profitable and reduce economic and social costs. Green initiatives are one example. Establishing an early childhood education system and primary healthcare teams are others.

I won’t attempt to graph or chart this phenomenon – it is too speculative; it is hard to project to next year, never mind 2015. The ESRI makes an attempt – over-optimistic in my view. They assume an unemployment rate of 6.4 percent by mid next decade. Therefore, we have two choices:

Wait (hope) for this to come true, leaving people on the dole in the meantime (with all the social dangers that entails).

Or, put the unemployed into work now and ease them out of any artificially stimulated employment into the new jobs the ESRI comes on stream. The former course, means amassing incredible debt levels as we borrow to pay for people on the dole; the latter, reduces this debt by creating ‘new taxpayers’ while at the same time investing into our productive base so that the ESRI’s projections have a better chance of coming true.

There is nothing given about any of this. There are no certainties. We may be facing into an extended period of low-intensity growth (as the World Bank has warned) once we come out of technical recession. An L shaped recession but may be long on both ends. There will be difficult, painful decisions to make – considerable economic and social demands with scarce resources, no matter how much is borrowed.

But we start from a more certain premise. On every measurement, with every new projection coming out – the Government’s strategy will not work. It was never going to work.

What is needed is a new government that understands that the economy is not ledger but a dynamic process, that employment and investment is the key, that a recession can only be overcome by growth strategies; a government courageous enough to defy the orthodoxy that is starving the current debate and offering us little else but more unemployment, more poverty, more debt – more of the same.

A politically brave government with considerable management skills.

The only question is: does such a government exist within the current set of political parties?

Leave a reply to Dr. X Cancel reply