Here is my challenge to the real devaluationists. Will any of them take it up? Real devaluationists claim that, since we can’t devalue our currency, we must devalue other inputs into the economy. Wages feature prominently as in cutting wages will increase our competitiveness. Many of these ‘real devaluationists’ are grouped around Irisheconomy.ie (Alan Ahearne was a leading figure until he went off to advise Brian Lenihan). Garrett Fitzgerald, one of the few commentators who have distinguished themselves in the debate over the recession, has unfortunately fallen into this thinking, too.

Here is my challenge to the real devaluationists. Will any of them take it up? Real devaluationists claim that, since we can’t devalue our currency, we must devalue other inputs into the economy. Wages feature prominently as in cutting wages will increase our competitiveness. Many of these ‘real devaluationists’ are grouped around Irisheconomy.ie (Alan Ahearne was a leading figure until he went off to advise Brian Lenihan). Garrett Fitzgerald, one of the few commentators who have distinguished themselves in the debate over the recession, has unfortunately fallen into this thinking, too.

So here’s my challenge: please explain the devaluationist argument in the context of facts, rather than assertion. I will offer space on this blog to any or all of them to write a guest post on this subject. For much of the arguments regarding wage cuts rests on the assumption that wages are uncompetitively high. Is this the case?

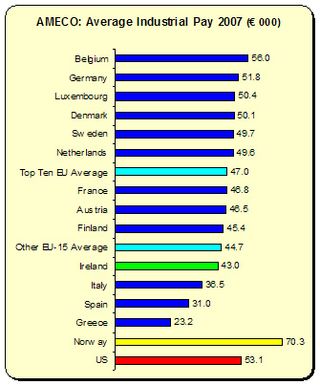

Let’s start with two databases. First, AMECO – the database of the European Commission's Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs – compares annual industrial employee compensation, a key figure in that it incorporates major sections of our export base.

As can be seen, Ireland ranks well down the league tables when it comes to average industrial pay – 10th out of the 13 countries reporting for 2007. Irish industrial wages are 4 percent below the other EU-15 average and over 9 percent below the average of top-ten EU economies (of which Ireland is one). In addition, we rank well behind other advanced industrial nations – Norway and the US.

The following, courtesy of a link from a friend, comes from Destatis, the German Statistical Board. This examines labour costs per hour in the 4th quarter, 2008 and covers private sector earnings.

Again, we see Ireland coming in slightly below the EU-15 average, but significantly behind the top-ten EU average – 12 percent below.

Again, we see Ireland coming in slightly below the EU-15 average, but significantly behind the top-ten EU average – 12 percent below.

Of course, we have to be careful regarding some the national figures. The UK, for instance, experienced a fall of 10 percent in labour costs in 2008. However, this is due to statistics being enumerated in Euros. The UK fall is a result of currency exchange rather than cuts in labour costs (there own devaluation experience). But there is another little insight in these figures.

While German labour costs come in below the top-ten EU average, the national distribution varies considerably. For instance, the former German Federal Republic (i.e. West Germany), manufacturing wages average over €46,000 while in the New Lander (i.e. formerly East Germany) the average wage comes in at €29,600. In the powerhouse region of the German economy, therefore, labour costs are higher than is stated in the above table.

'Real devaluationists’ (along with IBEC, ISME, Forfas, etc.) may point out that Irish wages have been increasing at a faster rate than other EU countries. In one respect, they are correct.

Between 2000 and 2007, Irish industrial wages increased by 38.9 percent while the other EU-15 average increased by 24.4 percent. So do they have a point? Not as much as this stat might initially suggest. There are three things to look at:

First, individual workers’ wages did not necessarily rise by that amount. A contributing factor is the changing character of the industrial base is changing. A number of indigenous enterprises and low/mid-skill multi-nationals have closed down or left. These would have been relatively lower-paid. They have been replaced by enterprises with higher-skilled, higher-value added jobs.

Second, there is a catch-up or ‘convergence’ factor at work. A crucial part of the argument to enter the EEC back in the 1970s – and to continue approving subsequent EU-based referenda – is the benefit of the Irish economy converging with the rest of the EU; in particular, with the top economies. Though we have some ways to go, this process is in train. So if convergence was a laudable goal in the past, why is it considered an obstacle now? It’s only an obstacle if we believe that Ireland will prosper only if we remain a relatively low-waged economy.

Third, there is considerable statistical manipulation going on here. For instance, in 2008 overseas ‘tourist trips to Africa increased by 39 percent while trips to Europe only increased by 5 percent. So are the Irish abandoning the romance of Paris for the challenging terrain of the Niger hinterlands? Hardly. Actual trips to Africa rose to 56,000, while trips to Europe increased to over 1.3 million. That’s the fun and games you can have when playing with statistics. So let us get up to our own fun.

Between 2000 and 2007 Belgian industrial wages increased by 25 percent while Irish wages increased by 39 percent. Obviously, our wage competitiveness has deteriorated substantially vis-à-vis Denmark. Or has it? Actually, Danish wages increased by €11,300 while Irish wages increased by €12,000. The actual cost difference to Irish employers is €100 annually. No one can seriously argue that €100 a year constitutes a ground for ‘real devaluation’.

At the end of the day, when wages make up approximately 6 to 8 percent of the manufacturing base, it’s hard to imagine how the real devaluationists think that lower wages will make any difference to Irish competitiveness – especially as Irish industrial wages are below average to start with.

Not only do the real devaluationists avoid this they avoid another consequence of wage slashing: the fiscal damage. With the Government flailing about over the collapse in tax revenues, real devaluationists want to cut revenue even further.

Let’s say we cut wages by 7.5 percent. Using Colm Keena’s table of income and tax revenue for 2008, this could, on average, reduce tax revenue by €1.2 billion. And this doesn’t count reduced PRSI contributions and spending tax revenue. And this doesn’t count the negative multipliers – reduced economic activity, driving enterprises dependent on domestic demand even further to the wall, or through it. And this doesn’t count the proportional rise in debt.

The real devaluationists count none of these things in their pursuit of the wild goose of competitiveness. And that’s the real problem – for if we go down their road, not only will we find ourselves in a cul de sac very soon, we will be amassing even more problems for ourselves.

So this is my challenge. Please explain how cutting wages will improve competitiveness when – on a cost basis – we have are a relatively low-waged economy. Please quantify the direct cost to the Exchequer and how exacerbating the fiscal deficit will help. Please examine the cost to the economy, through the negative multipliers and their impact on those parts of the economy dependent on domestic demand.

And please explain how slashing our living standards in pursuit of a highly contestable proposition will do anything else but impoverish people more.

So, to all the real devaluationists, you have been invited.

Leave a comment