Higher taxation is now on the agenda. The Left has long argued the virtues of higher taxation: more resources for health, education, infrastructural modernisation, childcare, social protection, elder-care, etc. We had little success – so enthralled has the nation been to the low-tax, low-spend model. Even social partnership was premised on cutting taxation (maintaining low wage increases in return for tax cuts to increase take-home pay).

Higher taxation is now on the agenda. The Left has long argued the virtues of higher taxation: more resources for health, education, infrastructural modernisation, childcare, social protection, elder-care, etc. We had little success – so enthralled has the nation been to the low-tax, low-spend model. Even social partnership was premised on cutting taxation (maintaining low wage increases in return for tax cuts to increase take-home pay).

Now everyone accepts taxes will have to rise – if, only, to help close the fiscal gap and, afterward, to pay for all this borrowing. This is not quite how the Left envisaged the debate. We wanted European-level of taxation to pay for European-level of services and living standards. Now, we’re going to get the high taxes but even worse living standards. So, perversely, the principle has been won – but not on the Left’s terms. So how do we get back into the debate?

There are two stages. During a recession I have argued that the last thing you do is increase general taxes on low and average income groups – those cohorts with a propensity to spend. Rather, you find less-deflationary sources of revenue, even as temporary measures.

However, on the other side of the recession what kind of tax system do we want? Falling back on ‘tax the rich’ and ‘close the loopholes’ demands, will only get us so far. We have to present a clearer picture – one that distinguishes us from the Orthodoxy and can win popular support.

As an initial contribution to this debate, I have examined the tax structures of other EU countries with the help of Eurostat's comprehensive Taxation Trends in the European Union. After all, we want to move in their direction. But what do their structures look like and what can we learn. There might be some surprising lessons here – and ones that the Left can exploit to its advantage.

Ireland’s Perverse Low-Tax, High-Tax Model

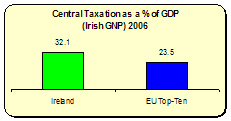

Ireland is a low-tax economy. In comparison with the top-ten EU economies (I’m using the top-ten because there is little sense in comparing ourselves with poorer countries es like Greece and Portugal where the average industrial wages are less than half of our own). Ireland is almost rock bottom. Only the UK is lower. We would have to raise nearly €8 billion more in taxes just to reach the average – and this doesn’t take into account the necessity of having to fund disproportionately higher capital investment to catch up with European levels of infrastructure.

Ireland is a low-tax economy. In comparison with the top-ten EU economies (I’m using the top-ten because there is little sense in comparing ourselves with poorer countries es like Greece and Portugal where the average industrial wages are less than half of our own). Ireland is almost rock bottom. Only the UK is lower. We would have to raise nearly €8 billion more in taxes just to reach the average – and this doesn’t take into account the necessity of having to fund disproportionately higher capital investment to catch up with European levels of infrastructure.

But while total Irish taxation is low Irish central taxation is high. According to the Eurostat report:

But while total Irish taxation is low Irish central taxation is high. According to the Eurostat report:

'Ireland is one of the most centralised countries in Europe . . . '

Central taxation covers those taxes that go directly to a country’s Exchequer and includes personal, corporate, indirect and capital taxation. Only the UK has a higher level of central taxation. Let’s turn to some of the main categories of Irish central taxation and see where the disparity lies.

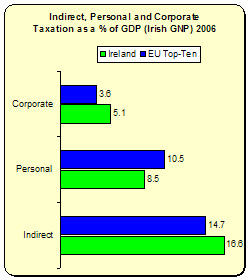

Indirect Taxes: In this category, including VAT, Excise duties and other taxes on products, we are nearly the top of the table. We have a disproportionately high level of indirect taxes – one of the more regressive taxes that states impose. We could reduce these taxes by 15 percent (reduce the standard VAT rate by 18 percent) and we’d still be at the EU average.

Corporate Taxes: Despite Ireland’s low tax rate, we have one of the highest levels of corporate tax receipts. There’s no contradiction here. A massive amount of ‘profits’ taxed here are earned somewhere else, courtesy of transfer pricing. As Michael Hennigan constantly, and correctly, points out:

Corporate Taxes: Despite Ireland’s low tax rate, we have one of the highest levels of corporate tax receipts. There’s no contradiction here. A massive amount of ‘profits’ taxed here are earned somewhere else, courtesy of transfer pricing. As Michael Hennigan constantly, and correctly, points out:

'Two of Ireland's biggest companies by revenue are owned by Microsoft. They have no direct staff and are operate from the offices of a Dublin law firm.'

There may be a number of reasons to raise corporate tax rates and end our tax-laundering system. But not because we don’t get enough corporate tax revenue.

Personal Taxation: Here we fall behind the EU average but not by much. The Eurostat figure understates the level of personal taxation because it assumes that the Health Contribution Levy is part of social insurance when in actual fact it is paid into the Exchequer. So, abolishing those regressive tax expenditure and shelters would probably bring us close to the average. There are still questions of balance within personal taxation – for instance, average income earners enter the top tax rate far too early.

When we examine central taxation and, for Ireland, its sub-categories, we find that we’re not low-tax; we’re relatively high-tax – in some cases the highest taxed. So how do we end up being a low-tax economy? There are two main categories.

Social Insurance

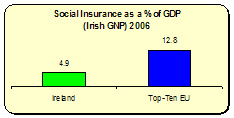

We are at rock bottom when it comes to social insurance. Actually, rock bottom doesn’t quite capture it. In fact, Ireland’s social insurance take is over-stated since it includes the Health Contribution Levy, as mentioned above.

We are at rock bottom when it comes to social insurance. Actually, rock bottom doesn’t quite capture it. In fact, Ireland’s social insurance take is over-stated since it includes the Health Contribution Levy, as mentioned above.

PRSI rates – employees, employers and self-employed – would have to be increased by more than 2 ½ times just to reach the top-ten EU average. That would mean increasing the PRSI rate for employees from 4 percent to nearly 10 percent, the employers’ PRSI rate from 10.75 percent to over 20 percent and the self-employed by a similar proportion.

[A little note: it’s interesting that, given our anaemic social insurance system that both Fianna Fail and the Greens campaigned in the last election on a platform of cutting social insurance levies even further.]

Local / Regional Taxation

There is no sense in putting up a graph on this one. Ireland hardly features. For the EU top-ten, local and regional taxation makes up over 8 percent of the GDP. In Ireland, it makes up a minuscule 0.8 percent. We’d have to increase this taxation base by over eight times and we’d still fall short of the average. But in other EU countries it is local and regional government that delivers many of the services and programmes that, in Ireland, is delivered by central government.

A New Basis for the Left’s Taxation Programme

So what can we make of all this? First, it is noteworthy how close we are to the UK’s centralised model. Like Ireland, the UK takes little in local/regional taxation and social insurance and is quite high in centralised taxation. The Left should argue for a profound break from this model – and centre it’s ‘tax’ demands on two areas – social insurance and local taxation.

Social Insurance: In most EU countries, a significant proportion of social protection and public services is delivered through the social insurance system. For the Left to adopt this model would have considerable advantages. People consider increased taxes as going into some kind of black hole. However, social insurance implies a specific contract: for x amount you pay, you will receive y amount of benefit. Here are two examples:

-

If PRSI was increased to include a specific ‘Health Insurance Levy’ (say, 2.5 percent) that might be more acceptable if people knew that they would receive free (or extremely low-cost) GP and prescription medicine. That’s a specific contract.

-

Further, if PRSI was increased to include a specific ‘Earnings-related Pension Levy’, again, this might be more acceptable if people know, as part that contract, they would receive 50% of their pre-retirement income in a pension.

We could go further – a small insurance levy for elder-care, including nursing homes, highly-subsidised childcare in best practice crèches and early education centres, pay-related unemployment and disability benefits. In addition, redirecting expenditure through an enhanced Social Insurance Fund would relieve pressure on the Exchequer finances, allow for increased investment in other areas such as social housing, etc., while providing a quicker route to fiscal stability.

Local Taxation: this would require even more radical surgery as our local government system is feeble, unaccountable and largely powerless. On every level, it is not fit for purpose. Before we could even begin contemplating higher local taxes, we would have to reconfigure a system of local governance that was devised in the 19th century. I will elaborate on this in a later post.

But, like social insurance, people might be more amenable to increased taxation if it went to greatly enhanced local/regional government. For they would see the benefit of their taxes in improved local services, enterprise supports, social programmes, amenities, etc.

* * *

A new Left programme begins to emerge:

-

Radically reform social insurance to deliver the benefits of free health, earnings-related pensions, income protection and other services such as childcare, etc. This will mean increasing PRSI rates but only as part of an identifiable contract that delivers the benefits.

-

Radically reform the local government system into a rational network of governance capable of employing greatly increased, and democratically accountable, powers. This is a pre-requisite to substantially increasing local/ regional taxation.

-

Reduce indirect taxes over the long-term (and put in the institutions that can ensure that the benefits of reduced VAT get to the consumer). This would reduce a regressive tax on low-average income groups.

-

Re balance personal taxation to ensure that average income earners do not enter the top tax rate. This would also mean tackling the difficult issue of when people enter the tax rate. This is a highly emotive issue – taxation on the low-paid; but it’s coming down the line. The Left has to argue for a progressive approach, otherwise the Orthodoxy, who just want to slap high tax levels on low incomes, will dominate the debate.

That’s the vision in broad outline. That we are in a recession doesn’t mean postponing the debate – it means we have to integrate transitional strategies into that long-term version.

So let’s get to work. And let’s, finally, lead the debate.

Leave a comment