Yes, it does look rather one-sided. IBEC, representing some of the most powerful financial and corporate interests, have called for payments to the weakest interests in society to be cut, i.e. cuts in social welfare. It’s like a bunch of ruffians getting tanked up in a pub on Saturday night and then going out to pick fights with the homeless.

Yes, it does look rather one-sided. IBEC, representing some of the most powerful financial and corporate interests, have called for payments to the weakest interests in society to be cut, i.e. cuts in social welfare. It’s like a bunch of ruffians getting tanked up in a pub on Saturday night and then going out to pick fights with the homeless.

I can understand that IBEC might be confused with all the blowback they're getting. After all, they are just being consistent. In their recent pre-budget submission, they have called for wage reductions of 10 percent, along with increases in income levies – leaving even average-paid workers pretty destitute. IBEC wants everyone one to share the pain. So why not social welfare recipients; they should be happy to swallow the IBEC pill. Take that cut, take it happily – you’ll feel better knowing you have made your patriotic contribution.

IBEC is aghast that the poor are making a killing in this deflationary market. This was pointed out by the joint stockbrokers’ submission:

‘Inflation-adjusted social welfare rates are set to rise sharply this year due to lower prices across the economy. The Consumer Price Index . . will drop by 4% in 2009 and may fall another 2% in 2010. Yet social welfare rates increased by about 3% in the Budget of last October. That translates into a real jump in welfare payments of 7% this year.’ 7 percent?'

My god, granny’s fleecing us. But before we start spilling out of the pub looking for people people to roll, let's examine the numbers.

First, one of the main drivers in falling prices is the decline in mortgage interest payments. They fell over the year by 25 percent. The impact of this fall is likely to be limited among low-income groups, especially among over 55s (if they own a house have probably paid it off by now) and young people. Another significant proportion of low-income groups are tenants and, while rents are falling, they are falling at only half the level as mortgages (local authority tenants receive no benefit in falling housing costs).

When the CSO excludes mortgage interest, inflation is still rising if only marginally. No doubt, this category will succumb to deflation but it will lag considerably behind the headline rate.

But there are categories that low-income groups disproportionately spend their money on. The big one is food. While, according to the CSO weighting formula, the population spends 10 percent of their income on food, we can reasonably assume this percentage is higher among low-income groups. Food prices are still climbing – nearly 1 percent over the last twelve months (meat has climbed 1.5 percent while oil and butter has shot up by over 8 percent). Electricity and gas has increased by over 17 percent in the last year – another category representing a disproportionate spend by low-income groups.

We could list a number of categories but suffice it to way it is not good enough to take a headline inflation rate, assume that low-income groups ‘benefit’ from the decline and then call for their rates to be cut. It’s a sloppy deduction.

And, yes, there’s something unseemly about sacrificing low-income people’s living standards on the alter of fiscal consolidation. This is not some abstraction. The EU’s Survey of Income and Living Condition report for 2007 shows the following:

- A quarter of all elderly living alone and private-rent tenants are at risk of poverty

- Nearly 40 percent of the unemployed are at risk

- Over 40 percent of local authority tenants are at risk

There are key categories almost entirely dependent on social welfare income. An incredible 96 percent of elderly living alone and 70 percent of lone parents would be at risk of poverty were it not for social welfare payment.

The main argument, however, is not so much that it would be ‘unfair’ to penalise these groups (it would be, in shed-loads). Nor is it so much about targeting those who ‘can afford to pay’ (though they should, in shed-loads).

The argument here is that increasing social welfare payments would actually help reverse economic decline, restore economic growth, and generally would be one of the better recession-busting policies at our disposal.

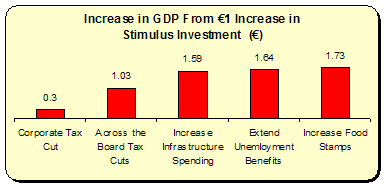

In the US, the background papers to President Obama’s stimulus package identified the multiplier effect of a number of different stimulus policies. Here I will use one, the calculations by Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Economy.com. Multipliers measure the $ dollar growth in the GDP for every $ of stimulus investment in the short-term:

Not only does public expenditure have a higher multiplier benefit than tax cuts, the highest benefit comes from transfers to lowest income groups. For every €1 increase in Unemployment Benefits or Food Stamps, the GDP benefits in the short-term by between €1.64 and €1.73.

Not only does public expenditure have a higher multiplier benefit than tax cuts, the highest benefit comes from transfers to lowest income groups. For every €1 increase in Unemployment Benefits or Food Stamps, the GDP benefits in the short-term by between €1.64 and €1.73.

Of course, you can’t transplant multiplier effects from a large home-market economy to a small open economy. But the general parameters are supported by IMF findings – namely, that public spending, on infrastructure and social protection, have a more positive impact; the latter especially because low-income groups have the highest propensity to spend.

Conversely, to cut social welfare payments will have similar negative multipliers. People on low-income will have to cut spending. This will reduce income to enterprises reliant upon domestic expenditure and, especially, those business and shops in low-income areas. If this happens, we will see more people laid, more wages cut, more businesses closed down.

So, if we want to increase economic activity and, at the same time, increase people living standards’ – one of the best things we could do is to actually increase social welfare payments; in a targeted and forensic way.

I have argued in the past for re-introduction of the pay-related element of unemployment (Jobseekers’) benefit – to maintain disposable income, reduce consumer anxiety, and provide sufficient income to utilise training and back-to-education schemes. Can we provide help to the low paid, especially those with dependent children – a group that certainly would have a high propensity to spend? Yes, through the Family Income Supplement (FIS).

There are a number of problems with this scheme. First, it’s means-tested and, therefore, has a much lower take-up rate than Child Benefit). Second, its current design has considerable claw-back mechanisms (the withdrawal of payment as income rises): up to 60 percent in worst-case scenarios.

But the scheme has considerable strengths, namely it can deliver considerable amounts of money to a very targeted low-income group. In 2007 there were over 22,000 recipients earning an average of €6,000 per year. The maximum amount you can earn – after tax – and still receive FIS is currently €26,000 (one child), €30,680 (two children), and an extra €5,000 for every child above that.

As well, it’s a pretty cheap programme. It costs only €140 million (though if the take-up rate was nearly 100 percent it would cost more) – only 6 percent of the cost of Child Benefit. So why not extend and increase the payments, to reach average income families, providing a huge stimulus for these families and to the economy.

There are other categories we could focus on – in particular, carers. They have considerable expenditure demands. To increase their payments would be a sure-fire way to increase spending in the economy. And we could look at in-kind benefits.

If the state ever gets around to rolling out a national, low-cost, childcare network they could, in the first instance, income-relate the fees. Given that, according to the OECD, states that lone parents in Ireland face the highest level of childcare costs (45 percent of disposable income), a reduction here would translate to higher consumer spending. There a lot of businesses and shops that would celebrate this policy development – because the parents would have more money to spend.

There is a school of thought that says that social welfare payments, like wages, are part of the economy’s problem. This school is a failed school. It has no proper credentials. It should be shut down. The living standards of low and average income earners are key to the solution, key to reversing the recessionary slide, and can provide us one more weapon in the fight to turn this economy around.

IBEC should pick on people their own size.

Leave a reply to D_D Cancel reply