'You do not get it. You are stupid. Do not demonstrate. Do not remonstrate. You are interfering in things you do not understand and you are making matters worse. Go back home. Sit down. Shut up. And let your betters sort things out.'

'You do not get it. You are stupid. Do not demonstrate. Do not remonstrate. You are interfering in things you do not understand and you are making matters worse. Go back home. Sit down. Shut up. And let your betters sort things out.'

End communication from your Econo-Overlords VMT (Von Mises Tendency)

I am getting increasingly annoyed by 'experts' lecturing us about our conduct in these recessionary days, a type of pre-blaming the victims. Dermot O’Leary, chief economist with Goodbody Stockbrokers, is the latest to step up to the lectern. He urges the nation to:

' . . . send out a signal to international markets about the ability of the State to pull together in a crisis. Television pictures of strikes on the streets of Dublin, Cork or Galway would not give that impression.'

But Dermot goes further:

' . . . no sane person would disagree with the need to take decisive action. In spite of this, workers hit by the recent pension levy are planning rallies in opposition to it.'

Wow, we're not only irresponsible, now we're insane. Well, there must be a lot of it about since only a minority believe that the pension levy is right. What is the cause of Dermot's concern?

‘. . . investors must be convinced the State can get its fiscal house in order, thus instilling confidence that this money will be paid back. If it isn’t, there is a possibility, as has been mentioned to me recently by a respected, experienced bond investor, of the bond market being closed to Irish bonds – at any price. That would render the State bankrupt.'

Don't you just love these policy prescriptions based on 'insider chats'? Here's a variation:

'I was having a pint in Doheny & Nesbit's and talking to a guy who knows a fellow who had been talking to another guy who heard about a Japanese dentist who was unsure about the coupon yield of the Irish Government’s new bond issue. If we’re not careful those workers and special needs kids will ruin everything.'

Exaggerated? Not by much. We’ve already had the Borrowing-Monster unleashed on us – even though our net debt is half the Eurozone average; and the Uncompetitive Wages-Monster – even when our wage levels are well below the EU-15 average; and let’s not forget the Public Spending-Monster – regardless that Irish current public expenditure levels are the absolute lowest in the EU (save for Lithuania). Now we’ve got the International Bond Investor-Monster to frighten us all back indoors. How unlikely is this doomsday (even our Dermot accepts it as 'unlikely')? Let’s run some numbers.

(And apologies if this gets a bit turgid, but the Right are using this argument with vehemence, so hopefully you’ll read on).

Don’t Panic

Government bond yields are a good weathervane as to the investors’ perception of the risk that a Government might default on its debt. The higher the yield, the higher the perception of a default; and, so, the higher the cost of borrowing. Therefore, low-yield good; high-yield bad.

Government bond yields are a good weathervane as to the investors’ perception of the risk that a Government might default on its debt. The higher the yield, the higher the perception of a default; and, so, the higher the cost of borrowing. Therefore, low-yield good; high-yield bad.

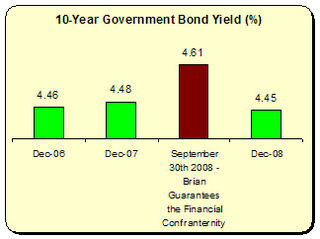

Yields on 10-year Government bonds have for the last couple of years hovered around the 4.5 percent range. At the beginning of this year, yields were still in this range. It should be noted that before and after the bank guarantee in September, there was very little movement, even though people feared a substantial increase in the cost of borrowing.

So far, though, no need to panic.

Volatility: Misreading the Cause

That's not to say there hasn't been volatility, especially since the beginning of the year. But some commentary has been wide of the mark. For instance, on the day the recent Framework talks collapsed and our Taoiseach went into the Dail to get macho on public sector pay, an 'expert' on RTE claimed 'the international markets approved' of these he-man policies because bond yields lowered. This is simply the wrong way to read the data.

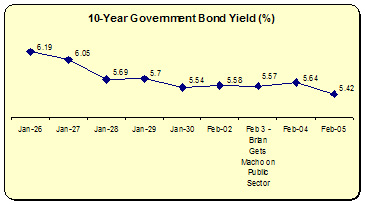

On February 3rd, bond yields dropped by 0.01 percent. But that was part of a near continuous fall since January 26th – when yields hit their highest this year. So bond yields were dropping even as the talks were going on, they dropped (fractionally) on the day the talks collapsed. And they continued dropping afterwards. To attribute the decline in bond yield to Brian’s macho actions is to ignore the trend.

Volatility: A Better Explanation

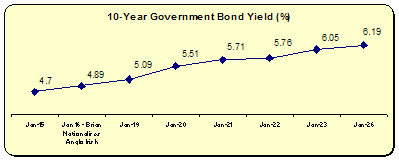

There was one event in January that really hit the bond markets. On January 15th year, bond yields were 4.7 percent, slightly higher than the historical trend, but not considerably so. Within ten days, bond yields went through the roof – rising to 6.19 percent. We were treated to talk of crisis and, like our friend Dermot, warnings that the market would seize up and leave us bankrupt. So what happened?

Did international investors spot some trade unionists congregating on the streets? Not exactly. Anglo-Irish Bank was nationalised because it was crashing and burning. This raised an understandable concern about the rest of the Irish banking system which still refuses to divulge the truth about its balance sheets. And, then, some bond folk remembered that there was this little bank guarantee – which, if ever redeemed, would sink the economy to the sea-floor.

Did international investors spot some trade unionists congregating on the streets? Not exactly. Anglo-Irish Bank was nationalised because it was crashing and burning. This raised an understandable concern about the rest of the Irish banking system which still refuses to divulge the truth about its balance sheets. And, then, some bond folk remembered that there was this little bank guarantee – which, if ever redeemed, would sink the economy to the sea-floor.

There are few conditions under which modern, stable nation-states renege on their debt – war, bubonic plague, maybe; and a financial crash which the state has undertaken to guarantee. It was this, not the state of the public finances that had bond markets concerned (our fiscal crisis had been known for months and bond yields didn’t really move).

ICTU Plans for Demonstration: Bond Yields Improve

To drive this point home, bond yields started to fall from the January 26th high of 6.19 percent to 5.38 percent by February 11th – still above trend but moving in the right direction. During this period those 'insane' trade unionists were preparing for demonstrations and even industrial action; every day we were lectured about the fiscal crisis (and how people 'just didn’t get it') but bond yields continued falling. Is there a cause and effect here? Hard to see.

But then something happened at end of last week. By February 13th bond yields rose again – to 5.62 percent. Funny, that was the two days when news broke of Irish Life and Permanent's little dance with Anglo-Irish. And when the full extent of Moody, Fitch's and S&P recent downgrade of the credit rating of both AIB and Bank of Ireland is fully absorbed, we may find the bond market reacting poorly.

The German Bond Gap

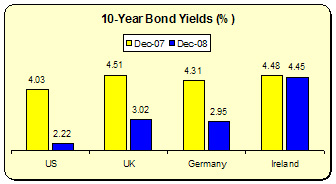

There’s another argument – ‘Son of Bond Monster’ – going the rounds: the gap between German and Irish bonds. It's been widening. This is another sure sign that if we don't slash wages and public spending then we are doomed, doomed. This is one more manipulation of data.

At the beginning of 2008, German 10-year bonds were yielding 4.31 percent – only a fraction of a gap with Irish bonds. By the end of last year, that gap widened to 1.51 percent. Were Irish bonds weakening? No, Irish bonds didn't budge at all as we saw. German bonds fell rapidly – all the way to 2.9 percent. During the year, investors were taking a bath in the equities market. So they transferred en masse to safe investments. German bonds are one of the safest you can find. This, naturally, drove down the yield for German bonds. It wasn't the poor performance of Irish bonds but the demand for safe investment havens that widened the gap.

At the beginning of 2008, German 10-year bonds were yielding 4.31 percent – only a fraction of a gap with Irish bonds. By the end of last year, that gap widened to 1.51 percent. Were Irish bonds weakening? No, Irish bonds didn't budge at all as we saw. German bonds fell rapidly – all the way to 2.9 percent. During the year, investors were taking a bath in the equities market. So they transferred en masse to safe investments. German bonds are one of the safest you can find. This, naturally, drove down the yield for German bonds. It wasn't the poor performance of Irish bonds but the demand for safe investment havens that widened the gap.

In fact, it happened with other government bonds; and in all the examples, these countries were slipping badly into recession and growing fiscal deficits. So why did they benefit and not us? One can speculate forever but I’ll venture an opinion: given that Irish bond yield seems to be tied closely to the health of the Irish financial because of the bank guarantee, most investors decided to go elsewhere.

Irish bond yield may not have suffered because of the bank guarantee (yet) but it didn’t benefit from the increased demand of investors for state bonds. Again, those damned banks.

A Word about Credit Default Swaps

Another measurement used in the ‘state won’t be able to borrow’ argument is the rising level of credit default swaps (CDS). These credit derivatives were originally devised as a form or insurance for the bond-holder against default. Essentially, you pay x amount over to a seller of the swap and, in the event your bond collapsed (either Government or corporate) you got back your money.

The problem now is that CDS is being reduced to an unregulated wild west of speculation and pure gambling. According to some estimates, a whole industry has ballooned – much like the sub-prime market derivatives – to $45 trillion. Yet, they’re covering assets of €25 trillion. Why the huge gap? Speculation. Like currency speculators, we are seeing ‘gamblers’ going short, going long, jumping in and out of the market to make a killing. (For the extend of this speculation, this is worth reading.

The CDS market tells us no more about the value of the government bonds then the price of oil, when-they spiked to stratospheric levels, told us about supply and demand. Oil prices were pumped by speculation. We may be seeing a similar pattern emerge with Irish bonds and CDOs. While one cannot ignore the movement of credit default swaps, they have to be viewed with a very wary eye. And we should not allow government policy to be bounced this or that by an increasingly perverted market.

In short, if you want to know the value of an Irish Government Bond, see what price investors are willing to buy them up at.

My Own Insider Chat

I, too, have chats with knowledgeable observers of the bond market. I met with one recently, not in Doheny & Nesbits but in a coffee shop off Parnell Street. He, too, expressed concern about the future cost of Government borrowing and difficulty in finding investors due to the fact that there are now high quality corporate bond and rights issues coming into the market, competing for investor money. So, I asked, what was harming Irish Government bonds. He wiped the crumbs of a scone from his hand and said:

'The bank guarantee – it’s like a block of cement tied to the national leg.'

Again, the banks. There is little evidence to suggest Irish ability to borrow in the future is being undermined by workers demonstrating or our deficit. Simply put, Dermot’s analysis doesn’t add up. Rather, high borrowing costs are intertwined by perceptions of our banking system which the Exchequer has guaranteed. And those perceptions are, understandably, not terribly upbeat.

So bring the banks into public ownership, create a bad bank to dump all the toxic assets in (or use Richard Bruton’s suggestion to create ‘good’ banks – different route, same destination).

And, then, ditch the guarantee. Get rid of the cement block. Otherwise we’ll blow billions recapitalisation and end up paying even higher bond yields; in other words, drown.

And read the data for yourself.

And always, always look for the politics behind those invectives against people who take up democratic action.

Leave a reply to Libero Cancel reply