David McWilliams has produced a table. In fact, two tables (I've collapsed it into one). Standing on these tables he spreads the gospel – in order to avoid bankruptcy and 'decades' of misery (decades, mind you) we must rip up the pay agreement and start slashing 'wildly over-paid' public sector salaries. We are on the verge of a new dark age if we don't act now. I don't know what accounts for David's apocalyptic language (he wrote the article from the island of Reunion, maybe it's the salt air), but he has taken up the manichean cudgels with a vengeance. Is it justified?

David McWilliams has produced a table. In fact, two tables (I've collapsed it into one). Standing on these tables he spreads the gospel – in order to avoid bankruptcy and 'decades' of misery (decades, mind you) we must rip up the pay agreement and start slashing 'wildly over-paid' public sector salaries. We are on the verge of a new dark age if we don't act now. I don't know what accounts for David's apocalyptic language (he wrote the article from the island of Reunion, maybe it's the salt air), but he has taken up the manichean cudgels with a vengeance. Is it justified?

As always, there are tables and then there are tables.

Wrong Categories, Wrong Result

David's table would certainly lead us to his conclusion. It seems to show that not only are Irish public sector salaries well in excess of other EU countries, they exceed the average private sector salary by close to €10,000 per year. This would seem game, set and match point. We might as well all go join David in Reunion and soak up the rays. Except.

David's table would certainly lead us to his conclusion. It seems to show that not only are Irish public sector salaries well in excess of other EU countries, they exceed the average private sector salary by close to €10,000 per year. This would seem game, set and match point. We might as well all go join David in Reunion and soak up the rays. Except.

There are considerable problems in David's numbers. First, his 'average public sector' pay figures don't actually refer to the public sector. In using Eurostat's Labour Cost Survey database, he has selected three NACE categories to make up this average public sector': L, M and N. The latter two refer to Education and Health – the classifications used by the Quarterly National Survey. The categories are valid – they comprise workers in these sectors. Except that Manus O'Riordan of SIPTU points out that:

'The QNHS data does not at all distinguish between public and private employment in either Health or Education. A good quarter of the QNHS Education total is in fact comprised of private sector workers, while over half those in Health are also operating in the private sector. QNHS totals for Health and Education should, accordingly, not at all be used as a proxy for their public sector component.'

In other words, David's public sector categories – Education, Health and Average Public Sector – are a mix of public and private (in the case of Health, a 50/50 mix). So we can't tell how much of his 'public sector' is actually 'private sector' pay. And we can't tell if it is more or less. But we can take a guess.

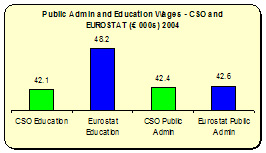

The CSO's Public Sector Earnings report can be more useful as it actually charts public sector earnings. If we compare the CSO findings with David's/Eurostat's findings we see that they converge on Public Admin. No surprise there – in all EU countries there is probably little private sector involvement in this category.

The CSO's Public Sector Earnings report can be more useful as it actually charts public sector earnings. If we compare the CSO findings with David's/Eurostat's findings we see that they converge on Public Admin. No surprise there – in all EU countries there is probably little private sector involvement in this category.

However, they diverge significantly on 'Education'. Bearing in mind Manus's point – that 25% in the 'Education' category used by Eurostat are private sector workers and that the CSO's report focuses exclusively on the public sector – we can see the considerable discrepancy – a discrepancy of over €6,000. We should treat this with caution – different agencies use different methodologies, which makes comparison difficult. However, it is more than arguable that David's figure, using Eurostat, is actually picking up private sector earnings – earnings that well exceed public sector earnings. This swells his 'public sector average'. He may rail at the high level of public sector earnings – but what he may actually be railing at is high private sector earnings.

David has inadvertently incorporated private sector earnings into his public sector figures - and it appears, deducing from the data, that these private sector earnings are much higher than their public sector counterpart. This undermines his apocalyptic language of 'wildly overpaid' public sector workers. But there's more.

Let's hone in on the one exclusively public sector – Public Administration. David takes his figures from the Eurostat Labour Cost Survey. What he attempts to show is that Ireland is alone in paying its public sector workers more than private sector workers. But in doing this he was very selective. The data he works off of shows:

-

That in the Eurozone countries reporting, public servants actually make more than private sector workers – nearly €3,000 more.

-

Of all the EU countries reporting (17 out of 27), in eleven countries public servants earn more than private sector workers. In only six do private sector earnings outstrip those of public servants. Now, most of these higher-earning public sector countries come from the New Members States. It could be argued, therefore, that they are not applicable to more advanced countries, since they have a weak private sector. But as I discuss below, that may very well be the case with Ireland also.

However we cut it, we have to admit – the picture is much complex than the simple 'sandy-beach' landscape David presents us. The wider public debate would have been better served had all the data – and not just a partial selection – been presented. As it is, all we have is pottage.

Accounting for Living Standards

When comparing wages between countries, one has to be very careful because account must be taken of living standards. To do this, we should employ power purchasing parities (PPPs) – the 'how-much-bread-you-can-buy-with-a-Euro' measurement. If we do, we find the difference between public sector pay here and in other countries narrows considerably.

David shows in his tables that, of the countries reporting, Irish public sector pay is, on average, €5,345 more than their counterparts. However, when PPPs are applied, this gap shrinks by half – to €2,700. Okay, it's still higher – but it hardly justifies David's end-times prediction.

The Cost of Public Sector Workers

But there's another measurement to look at, for David's argument is not just based on a 'it's-not-fair-public-servants-earn-more-than-private-sector workers' contention. David's argument is profoundly eschatological – he is posing the end times of our economy because we can't afford to keep on paying these 'wildly over-paid' public servants. If we do, say your prayers. So is this the case?

The same Labour Costs Survey measures the actual cost to the State of hiring public sector workers. This includes wages, of course, but also social insurance contributions, pensions, training, allowances, etc. So is the Irish State paying too much too its public servants? Not by a long shot.

Ireland lags behind all the countries that David selects. Among the five countries, Irish public servants are the fourth cheapest (e.g. it costs the Netherlands nearly €55,000 per public servant – an Irish public servant 'costs' the Government nearly €46,000). Pity David didn't point this out.

The Public Sector – Private Sector Differential

We saw that David's argument – that there is a €9,900 pay differential between the public and private sectors – was deeply flawed because he selected and compared the wrong categories. But is there a differential, and how much is it? Let's be clear – this is a debate that is often subjected to smoke-and-mirror arguments. So let's tread deliberately.

David is correct to show up the gap between public servants (those in Public Adminstration – the only truly public sector category we have to work with) and private sector workers. It's nearly €7,000 in favour of the former. So are public servants paid too much? Or are Irish private sector workers paid too little?

In David's table, Irish private sector workers earn less than the average in the other countries - €1,200 less. But if we put this through the PPP wringer, we find Irish private sector workers earning substantially less: over €3,000 less. Or about 11 percent.

UNITE the Union has gone over this ground rather comprehensively. Using OECD, EU AMECO and Eurostat figures, it has shown that Irish private sector workers are well into the bottom half of the Euro wage league – whether nominally or through PPP. So here's the kicker: were Irish private sector workers paid on a par with other comparable EU countries (the wealthiest ten countries), they would still trail the public sector – but only by about €55 per week.

You know what that €55 would b equal to? The same differential in the Eurozone countries. In other words, Ireland would not – as David would have it out – be out of step. It would be average.

€55 per week – is this justified? One could go down a bottomless well arguing that toss but here are a few facts:

-

SIPTU's Marie Sherlock and Lorraine Mulligan point out that nearly 70 percent of public sector workers have a third-level qualification, compared to only 28 percent in the private sector. The CSO shows there's a €14,000 per year gap between those with third level education and those with a Leaving Cert. So can anyone be shocked that public sector pay is higher? In fact, the gap between the public and private sector is much less than the gap based on educational achievement.

-

The Government is the largest employer in the state. Given that the size of the firm is a major determinant of pay, how do 'large employers' compare? Public Administration workers average €21.47 per hour. Private sector workers in firms that employ between 500 and 1000 people average €20.10 per hour while those employed in firms with a 1000 or more average €19.06. A difference, yes, but a small one.

-

Again, the SIPTU researchers show that over the last two and a half years, private sector earnings have exceeded those of public servants. Industry and business services experienced a 10.1 percent increase; public servants have received a 8.6 percent. More interestingly, when inflation is taken into account, private sector workers have seen their wages fall by between 2.1 and 2.8 percent. Public servants have seen their wages fall by 4.1 percent. Cut wages? Wages are already being cut.

* * *

What does all this number-crunching mean? First off, it means that if you're going to do statistical comparisons make sure you get your categories and your measurements right. Second, when all the factors are accounted for, public sector workers, on average, are not living high off the hog (2.5 percent of private sector workers earn more than €50 per hour – only 1.5 percent of Public Administration earn this amount; and this doesn't' count the self-employed). Third, private sector workers should be looking at their own employers and demanding to know why their labour isn't valued as high as it would be in other countries.

But, most of all, this means that public sector workers are being scapegoated – blamed for the fiscal crisis we're in. And there is a concerted attempt to divide public and private sector workers – to get one group to blame the other.

Instead, we should be pointing the finger at the neo-liberal dogma that has been shoved down our throats for over a decade, the squandering of billions on a property boom that enriched a few, the inane corporate policies that has brought our banking system to the brink, the right wing policies of the bobbsey-twins – Fianna Fail and Fine Gael.

Is there a problem with public sector wages? I'd be surprised if there wasn't. We have one of the highest wage inequalities in the EU, we have an 'incomes' strategy that controls one type of income – wages – while self-employed and capital income is allowed to go on its merry way unfettered, our wealth is so concentrated that 75,000 households own over €325 billion in capital assets (and I bet not one of those households is employed in the public sector). With a wage/income structure so disfigured, I have no doubt that it wreaks havoc throughout the economy.

At the end of the day, this is a political argument. Of course, all sides marshal the data to support their argument. But there is a special onus upon commentators – whether in the mainstream or online media – to use that data in a way informs, not obfuscates. So we can crunch the math all we want, but clearly the numbers look a lot different in the balmy climes of Reunion.

Because here in the cold and the frost and the winter that is our economy, they aren't telling the same story.

Leave a reply to Tomaltach Cancel reply