With Exchequer finance spiraling out of control, what should the Left argue? Shore up capital spending? Cut current expenditure (i.e. public services, wages, social programmes)? Increase taxes? What should the Left’s prescriptions be? How can we show the public that we have a handle on these matters? What is the best way forward?

With Exchequer finance spiraling out of control, what should the Left argue? Shore up capital spending? Cut current expenditure (i.e. public services, wages, social programmes)? Increase taxes? What should the Left’s prescriptions be? How can we show the public that we have a handle on these matters? What is the best way forward?

Difficult one. A right-wing government recklessly allowed the nation’s finances to become over-dependent on property-related revenue; they broke it and we’re asked what we would do to fix it. So here goes – my own suggestion for what it’s worth: don’t argue the issue in the narrow fiscal 'increase-tax or cut-spending' context. In the first instance, damn the Maastricht guidelines and borrow, borrow, borrow. There, I said it. I feel a lot better.

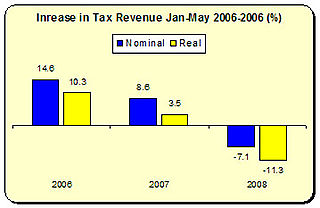

Tax revenue is plummeting. In the five months to end of May, we are taking in less than last year and only slightly more than two years ago. But these are nominal figures. Factor in inflation. and we will be facing into a considerable decline. A number of commentators suggest we will be taking in €3 billion less this year than projected. But over at Finance they’re drawing up even gloomier worst-case scenarios – revenue plummeting to between €4 billion and €5 billion below target. That’s a lot of dosh – especially considering that we were running a budget surplus only a short-time ago.

Tax revenue is plummeting. In the five months to end of May, we are taking in less than last year and only slightly more than two years ago. But these are nominal figures. Factor in inflation. and we will be facing into a considerable decline. A number of commentators suggest we will be taking in €3 billion less this year than projected. But over at Finance they’re drawing up even gloomier worst-case scenarios – revenue plummeting to between €4 billion and €5 billion below target. That’s a lot of dosh – especially considering that we were running a budget surplus only a short-time ago.

However, all is not bleak. On the current side – day-to-day spending – we are still in surplus. That means we still take in more money in tax than we spend through all the Government departments. The immediate reason for the rising debt arises out of the capital expenditure – which is one of the highest in the EU as a percentage of total wealth (it needs to be, we have one of the worst infrastructures in the industrialised world).

So, there really shouldn’t be a problem because debt-financing capital investment is a normal thing – especially as the improvements in the infrastructure should, in theory, increase growth and productivity in the future. But there’s those damned Maastricht guidelines.

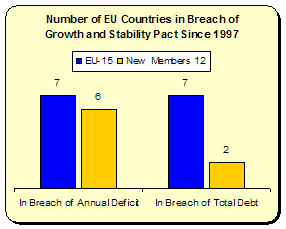

The Maastricht Guidelines, now called the Growth and Stability Pact, were established back in 1997 and aim to limit annual Government deficits to no more than 3% of the GDP. Further, Governments are not supposed to have a total debt of more than 60% of the GDP. Breaching these guidelines would risk being hauled up in Europe and being fined – never mind the existential shame of being labelled a reckless spendthrift.

Ireland is now close to breaching those guidelines. Davy Stockbrokers estimates that this year the general government deficit will reach 2.7% – dangerously close to the limit. However, next year we will easily exceed that limit. We will be in for a good spanking by the guardians of fiscal probity.

To avoid breaching those guidelines we could (a) cut back on capital investment (not a good idea of if we aspire to a modern European infrastructure); (b) cut back on current expenditure – hospital ward closures, crowded schools, more traffic congestion, increased poverty and reduced living standards: a great way to pile on the misery on a already miserable situation; or (c) we can raise taxes which is hardly a brilliant idea in an economic downturn (people spend less, retail sector plummets further, more job losses, less investment – that’s just a taster).

None of these options are palatable. Yes, we could revisit the capital expenditure programme to ensure money is spent wisely, we could subject current expenditure to a rigourouss social cost-benefit analysis (when our primary schools are in massive debt, is it equitable to subsidise fee-paying schools?), we could raise taxes on high incomes – but in terms of alleviating the deficit it would make only a small impact.

For all this ignores a fundamental fact: the current fiscal crisis arises out of a relatively low-waged economy that has relied on property/consumer spending and foreign capital for its growth. The problem is structural and if the Left tries to argue on the basis of fiscal remedies it risks being trapped in a debate set by the Right. If the Left is to make an economic impact, it must direct people’s attention to the real underlying problems and not go along with this ‘if only we could just get through the next couple of years we’ll be okay’. But in the meantime it must come forward with a set of proposals to address the immediate problem. And that is to borrow – over and above the Maastricht guidelines.

What would be the consequences if we took that action? Nothing. Europe wouldn’t say boo. Because country after country ignores those guidelines already – at times enthusiastically so. Take, for example, the main engines of the European project. Germany missed the limit in both 2004 and 2005. France, which is likely to surpass the 3% limit this year, has a debt ratio of 64.2% and a current, or day-to-day, deficit. What action has the EU taken against these countries? Zip. Even when Europe dragged poor Portugal and Greece into the dock – they huffed and puffed but fell short of taking any action, probably because it would look a tad inconsistent if larger, richer nations could flout the guidelines but smaller poorer countries were victimised.

The fact is a lot of countries are doing it. Nearly half of the EU-15 countries have been in breach of the 3% annual deficit criteria while, nearly half are currently in breach of the total debt criteria. Ireland would be joining a crowd. Ireland could make a better case than most for breaking the guidelines. We are, after all, running a current surplus, our total debt is 25% of GDP, compared to a Eurozone average of 68% (in breach of the guidelines) – the second lowest in the EU. And the reason for breaching the guidelines is to finance capital investment, not day-to-day spending.

The fact is a lot of countries are doing it. Nearly half of the EU-15 countries have been in breach of the 3% annual deficit criteria while, nearly half are currently in breach of the total debt criteria. Ireland would be joining a crowd. Ireland could make a better case than most for breaking the guidelines. We are, after all, running a current surplus, our total debt is 25% of GDP, compared to a Eurozone average of 68% (in breach of the guidelines) – the second lowest in the EU. And the reason for breaching the guidelines is to finance capital investment, not day-to-day spending.

Even if our case is not accepted – so what? Breach them anyway. It’s not like anything will happen to us. While some fiscal conservatives may warn of the damage to Ireland’s ‘fiscal image’, its not like multi-nationals are going to avoid us because we’re investing in our infrastructure to the point that we rise above a problematic guideline which other countries have ignored and which Romano Prodi, former EC President, once described as stupid. Of course, breaching guidelines so soon after the rejection of the Lisbon Treaty might appear, on the surface, to be a bit gratuitous.

But that ignores the very strong case Ireland would have for exceeding the 3%, and it ignores the conduct of other countries. And we can always get our found friends in UKP and the Tory parties to organise another green T-shirt day in the EU Parliament – this time with a ‘Respect the Irish Deficit’.

That’s the case the Left can make. But it’s not the end of the argument, merely the beginning. To argue for borrowing is to argue for a tool, something more than just a ‘tide-us-over’ exercise. From this platform we can then discuss the damage of unleashing the property market, the narrowing of the tax base, the lack of an enterprise strategy to grow and develop the indigenous sector; a borrowing policy is a gateway policy to other areas. And it allows us, temporarily, to escape the ‘increase-tax, cut spending’ trap the Right would set for us.

And if on the way we can cast doubt on the Government’s ability to manoeuvre through this (remember the last time Fianna Fail went on a borrowing splurge – when they were trying to kick-start indigenous business through demand-led policies in the late 1970s?); if we show that they cannot be trusted to do it right, that they were the ones who actually got us into this mess – then we will begin to enter the wider economic debate.

Now where’s our bank manager?

Leave a reply to Niall M Cancel reply