The Taoiseach recently criticised the demand for new electricity credits. Addressing Sinn Fein in the Dail:

“You want to add another €2 billion to it in terms of a short-term intervention [electricity credit], which would apply to very, very wealthy people, millionaires who will benefit from your proposal.”

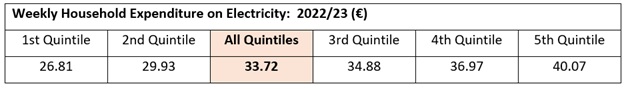

Yet, that’s exactly what the Government is doing – giving millionaires more money – by extending the VAT cut on electricity out to 2030. In fact, millionaires benefit more from a VAT cut than they would from an electricity credit. This is because the more electricity you ‘buy’ the more VAT you will pay and, so, the greater the benefit from the tax cut. According to the CSO’s 2023 Household Budget Survey, the 5th quintile (top 20%) spends 50% more on electricity than the lowest quintile.

Let’s do a stylised exercise and assume that the above weekly expenditure excludes VAT. Further, let’s annualise the amounts. This will allow us to see the cash benefit to households from reducing the VAT rate to 9%, which the Government did in 2022.

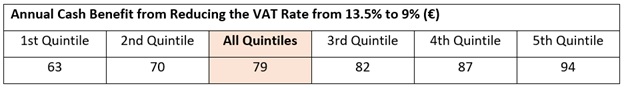

Unsurprisingly, the highest consumers of electricity – the top 20% – receive the highest benefit from the tax cut.

Now compare that with an electricity credit. If the cash benefits from the VAT cut were turned into an electricity credit it would be approximately €79. That would amount to an increase for the bottom 40% of households (1st and 2nd quintile) and a reduction for the top 20%. A flat-rate electricity credit would be more equitable than a VAT cut.

Introducing Democracy into Price Markets

The above is not an argument for an electricity credit, however. True, if you had to choose between the two – credit or tax cut – you would choose the former, though its more expensive. But there are two credible objections to credits.

First, while we can hope that electricity prices track general inflation (2% per year out to 2030), there any number of unpredictable events – supply chain interruptions, rising demand (especially from data centres), sluggish roll-out of renewable sources, etc. Electricity credits are subsidies chasing prices. Do we introduce a credit every time there is a glitch in the market?

Second, electricity providers could factor in the credits into their prices. For instance, if a household receives a €250 credit, would we be surprised if providers increase prices by €50 to grab some of that credit? In this instance, electricity credits subsidise providers’ profit margin.

These arguments are not fatal to introducing electricity credits. But it should provoke us to find a better solution to energy prices. For instance, we could start to reshape price markets.

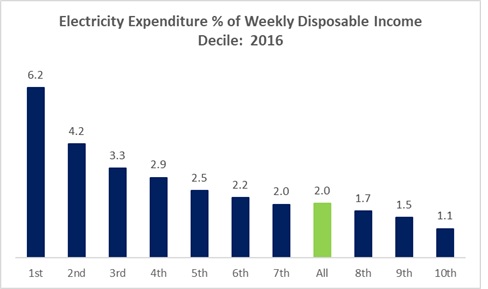

Energy prices are, by their nature, very regressive. Though this comes from the 2016 Household Budget Survey (the CSO doesn’t provide household income in the 2023 Survey), the relationship between prices and income will not have qualitatively changed.

Households in the lowest income decile paid more than 6% of their income on electricity. At the other end, the top decile, households paid 1% of their income on electricity. We need to start tackling this regressive impact.

I consider one example here – Universal Basic Energy. Under this proposal, every household would receive a free of amount of electricity. Electricity retailers would then compete over prices above that free energy threshold which would include recouping the cost of free provision. This would reduce energy poverty. For many households the free electricity allowance could cover most of their current energy expenditure. Further, it would incentivise high-income households to reduce electricity consumption reduction (conservation, retrofitting); in other words, those households that can afford it.

Of course, the free allowance could be provided for a small per unit price – but at a rate that would reduce electricity prices for the majority of households. The point is to address the regressive impact of ‘market pricing’.

This is known as block-tariffing – the price of per-unit electricity increases as consumption rises. This is nothing new for many European countries. Spain, Slovenia, Italy, Netherlands, France, Germany and Hungary operate some form of block-tariffing though designs differ.

Or we could compare it to the tax system whereby the initial amount of income is tax-free (though tax credits) with income above that threshold being taxed.

* * *

Rather than tinker with subsidies – whether through tax cuts or direct household payments – we should reshape prices to make them less regressive. This will take time to design, consult, pilot, evaluate and implement. In the interim we could consider:

- Some form of temporary support of households – including electricity credits.

- Launch a full investigation into price-setting in the electricity market – according to the ESRI, it is difficult to establish why Irish electricity prices are so high

- The abolition of standing charges. If consumption of electricity is inherently regressive, standing charges are a regressive levy on top of that. They can rise to over €200 per year, regardless of how much electricity you actually consume. So abolish these charges or reduce them to a level that is not a regressive burden.

These steps, combined with the goal of a Universal Basic Energy, would send a positive signal – that the state is ready to reshape market prices to ensure a more efficient outcome. We may not be able to control every factor that feeds into prices, but we can design markets to make them more responsive to social need.

It’s called democracy.

Leave a comment