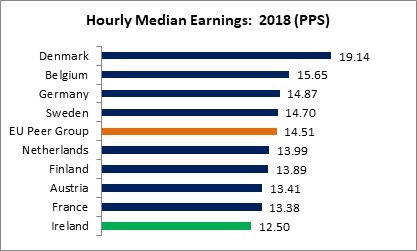

Ireland is a low-earnings economy.

There’s Ireland – at the bottom of our peer group table. Median wages would have to increase by 16 percent to reach our peer group average (median earnings are that point where half of employees earns less and the other half earns more).

When compared to the entire EU, Ireland doesn’t fare well either. We are only a small percentage (3 percent) above the overall EU average. And that includes much poorer economies such as Poland, Romania, Greece, Portugal and Bulgaria.

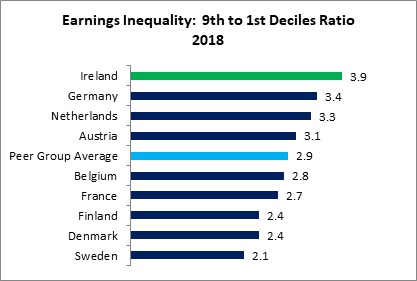

Not only are we a low earnings economy, we are a highly unequal economy.

In Ireland, employees the 9th decile earns nearly four times more than employees in the 1st decile. The peer group average is less than three times while in Sweden it is twice. We’d have to cut earnings inequality by half to compete for best practice.

We can get a further insight into our earnings inequality by comparing hourly earnings in the 1st and 9th deciles.

In the lowest-earning decile, Irish earnings are at the bottom of the table. However, when we come to the 9th decile, Irish earnings rank second. This helps explain our high inequality ratio. For a contrast, note Sweden’s rankings: 2nd highest among the lowest earners and bottom in the 9th decile.

It’s bad enough that we are a low earnings, highly unequal economy. Another problem is that we seem to be going backwards. Whether measured in Euros or purchasing power parities (PPS), average median earnings are falling over the medium term. Between 2006 and 2018:

- Average median earnings fell by 0.8 percent (Euros)

- Average median earnings fell by 9.6 percent (PPS)

This was during a period when average median earnings (Euros) rose by 20 to 30 percent in other small open economies (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland and Sweden).

Just to note: we have to be cautious about earnings trends due to the composition effect. For instance, if it was low-paid sectors or occupations that suffered a faster decline in employment than the national average then the composition of the workforce that we are measuring has changed. And with fewer low-paid, the overall average would rise.

It’s one thing to point out the fact of wage inequality; it’s quite another to construct effective policies to close that gap. There is a tendency to see low wages and earnings through the lens of the national minimum wage. No doubt statutory wage floors can be a significant tool in the fight against low pay.

However, it is worth noting that the economies with the lowest levels of earnings inequality and the highest level of earnings in the 1st decile – Denmark, Finland and Sweden – do not have a statutory minimum wage. How do they do it? Through extensive collective bargaining where employees in the lowest paid sectors have a voice; combined with a more egalitarian political culture.

To close inequality gap, to raise people’s earnings and living standards we need a range of policy instruments. But clearly, giving workers – especially those in low paid sectors – the tools that enable them to fight low pay is one of the best ways to get out of our low earnings rut. In short, we need more democracy in the workplace.

Leave a comment