In the run-up to the budget we will hear a lot about how the Government spends a lot or not enough, and needs to spend a lot less or more. While there is considerable scope for legitimate disagreements, let’s at least get the context right. For instance, does Ireland spend too much in comparison with our peer group in Europe? Are we a high or low spender?

Different Ways of Categorising Spending

Comparing public spending is not straightforward. Countries have different ways of spending money on ‘public goods’, but not all of them are considered state spending. Some spending is conducted by non-state bodies; for instance, spending on housing and water/waste in other EU countries is done through off-balance sheet vehicles such as public cooperatives or public corporations. Then there is social protection spending which is organised through civil society organisations (the Ghent system in countries such as Belgium and Sweden where trade unions operate unemployment insurance schemes); these do not necessarily appear on the state balance sheet.

Finally, there are demographic issues. Countries with a high proportion of pensioners will (or should) spend more on pensions, while those with a higher share of young people will spend more on education and family supports. Demographics even apply to policing: countries with younger demographics or high levels of youth poverty are likely to need more policing.

There is no one formula to accommodate all these contingencies and differences.

What Measurement?

There is also the problem of how to measure public spending. We know, for instance, that assessing public spending as a proportion of GDP will wildly understate Irish spending. We can use the CSO’s measurement of modified Gross National Income (or GNI*) for Ireland, but it can give a slightly skewed result since we don’t have a similar modified measurement for other EU countries. For instance, the CSO removes intellectual property depreciation and aircraft leasing when calculating their GNI*, but we can’t do that for other countries to get a like-for-like comparison.

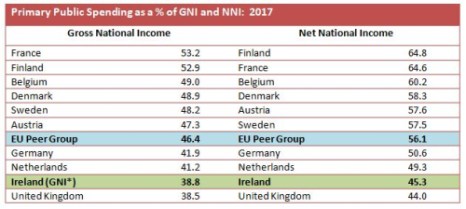

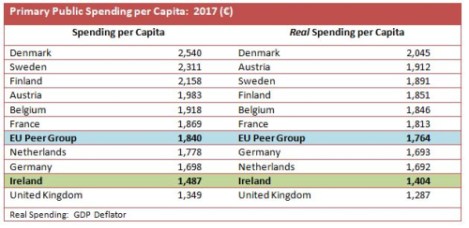

Acknowledging these caveats and differences, let’s see what we can come up using three measurements:

- Gross National Income with the CSO’s GNI* measurement for Ireland

- Public spending per capita – this is a measurement used by the Nevin Economic Research Institute

- Net National Income – this is not used as much though, for comparison purposes, it is probably more robust than Gross National Income. It essentially removes capital depreciation in much the same way as the CSO removes intellectual property depreciation to obtain their GNI*.

Using these three ways of measuring ‘primary public spending (excluding interest payments), what do we find?

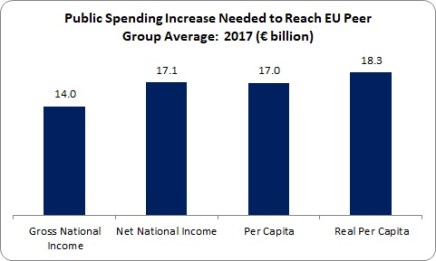

In all measurements Ireland is at the bottom of our EU peer group, exceeding only the UK. On the basis of the above, we can estimate the amount of additional public spending needed to reach our EU peer group average.

Ireland would have to increase public spending by between €14 and €18 billion to reach our EU peer group average, or between 20 and 26 percent. However, this does not factor in key variables.

Demographics

As noted above, demographics drive a substantial proportion of public spending. For instance, people aged 65 and over make up 20 percent of our EU peer-group population; in Ireland, they make up 14 percent. There are two ways to adjust for this:

- If we just exempted expenditure on social protection pensions, the gap between Ireland and our EU peer group would fall to between €5.2 and €8.6 billion.

- If we were to adjust by assuming that Ireland has the same proportion of elderly as our EU peer group, then the spending gap would be between €9.4 and €13.7 billion.

The reason these figures differ is because not only do other EU countries have an elevated age demographic; they also spend more on pensioners (per elderly capita).

However, when we turn to young people, it is Ireland that has an elevated demographic: 27 percent of the Irish population are 19 years or younger compared to 21 percent in our EU peer group. At the same time Ireland under-spends on education on a per pupil basis. Different ways of measuring this gap shows that Ireland may be spending €2 billion less than our EU peer group average on education.

Another category impacted by a high youth demographic is social protection spending on families and children. A back-of-the-excel-sheet estimate shows Ireland, because of a higher demographic and lower per capita payments, could be spending approximately €1 billion less than our EU peer group average.

Fiscal Capacity

While we should be hesitant about putting a definitive number on it, it appears that when age-related spending is factored in, Ireland – using the conservative GNI measurement – spends somewhere between €8 and €12 billion less than our EU peer group average, and this could be an under-estimate. Of course, merely increasing spending is no guarantee of quality or efficiency (though underspending is sure to undermine quality).

But this raises the question of our fiscal capacity to meet the current challenges: the fastest growing elderly demographic in the EU, Brexit, a global trade slowdown, the climate emergency, Eurozone stagnation and the housing crisis – to name only a few.

Increasing our fiscal capacity, however, is not something that can be done in the short term. It requires a long-term strategy consistent with the economic cycle. Raising resources for public services, social protection and investment to European levels would mark a systemic break with our historical low-spend economy. We squandered the opportunity to start this strategy in the years following the recession, and now we are heading into what could be a storm.

Let’s hope the Government doesn’t set us back with unnecessarily tight budgets in the years ahead.

Leave a comment