The Revenue Commissioners have produced some interesting data relating to incomes over the period of the recession and the beginning of the recovery. What’s noteworthy is the reversal of fortunes between low/average and top income earners in these two periods. There are some caveats in the data.

· First, Revenue income data includes those with occupational incomes which are taxable. So the following data includes more than just those at work

· Second, incomes do not include contributions to pension schemes; therefore, this is likely to understate incomes at the higher end.

· Third, this counts cases, not individuals. This is important when it comes to ‘married’ cases where there are two earners but only counted as one tax case.

Keeping these caveats in mind let’s see what stories the data may be telling us.

Over the period of recession and stagnation, median incomes (the point at which 50 percent earn above and below) increased while the incomes at the top declined – for the top 0.1 percent, quite substantially. We should note that the rise in median incomes doesn’t mean that all or most received income increases. This could include the compositional effect whereby people lost their jobs, changing the make-up of the group we are measuring.

For those at the higher incomes, the decline was due primarily to the self-employed (property-related?). The EU Survey of Income and Living Conditions shows that employee (PAYE) income rose between 2007 and 2012; however, self-employed income fell by nearly two-thirds.

The story changes, however, when the recovery set in. Between 2012 and 2015, median income fell marginally by 1 percent. However, the top 10 percent saw incomes rise by 2.1 percent while the top 1 percent and top 0.1 percent experienced income increases of 3.6 and 6.8 percent respectively.

Other Revenue data confirms this trend.

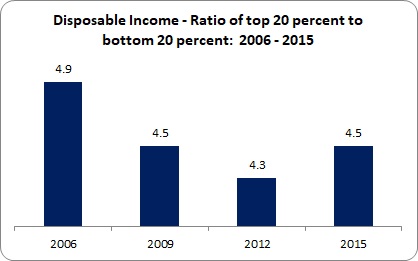

Prior to the crash, the top 20 percent earned 4.9 times that of the bottom 20 percent. This fell during the recession but started rising with the recovery. This is consistent with the data above.

While Revenue shows rising inequality among income tax payers, there is other data that shows inequality falling.

This Gini coefficient measurement refers to market incomes (before social transfers) and covers the entire population, not just those in work; the higher the number, the higher the inequality. We see Ireland returning to pre-crash levels; and in contrast to Revenue, inequality has fallen since 2013. .

We should note, though, that Irish market inequality remains substantially higher than our peer group. Indeed, it is the highest in the entire EU, not just our peer group. Returning to pre-crash levels is not enough from an equality perspective. And if the trends identified in the Revenue data persist, Ireland’s Gini coefficient could start to turn north.

Three policy responses (among many) are needed to address in-work in equality:

· First, collective bargaining: there are indications that sectors with high levels of collective bargaining rise to the average of our peer group (along with those sectors where there is high labour demand such as the ICT sector). However, those sectors with low bargaining coverage and union density fall well behind. Collective bargaining – especially in the large domestic sectors such as retail and hospitality – would boost wages and working conditions and make a substantial contribution to closing the inequality gap.

· Second, increase the social wage – that is, employers’ social insurance and introduce new in-work innovations such as pay-related sick pay and pay-related maternity benefit. We are an outlier by not linking social benefits with income. This, again, would boost low/average incomes especially as many high-income earners already benefit from workplace schemes designed to protect incomes.

· Thirdly, limit precarious contracts by not only facilitating collective bargaining across sectors, but introducing minimum requirements regarding certainty of working hours, temporary contracts and, specifically, public sector and public agencies’ outsourcing.

We shouldn’t always think that inequality is about taxation and social transfers (though there is that). The inequality that flows from the workplace must be addressed in the workplace. And we can do this without resorting to fiscal space gymnastics. But the benefits – in terms of increased tax revenue (though higher wages) and higher consumer demand (through social benefits and certain working hours) – shows that reducing inequality can be a win-win win situation; for the workers, the Exchequer and domestic businesses reliant on the spending power of workers.

Leave a comment