Following an exchange of graphs on Twitter with Seamus Coffey (@seamuscoffey), chair of the Irish Advisory Fiscal Council, I did some looking around Eurostat’s Structural Earnings Survey database. This dataset focuses on employee earnings. We can not only compare Irish wages to other EU countries, we can look into the ratio of high wages to low wages. The news isn’t particularly good. The following focuses on the business economy which can be used as a proxy for the private sector.

The SES comes out every four years so the data lags a bit but is still relevant.

Unlike the average wage, the median wage measures the mid-way point at which 50 percent earn above and 50 percent earn below (if we were to measure average the pattern would be pretty much the same).

We find that Ireland is well down table, above France and the UK. To reach the mean average of the other countries, the Irish median wage would have to increase by 8.6 percent, or nearly €3,200.

But not all employees rank towards the bottom.

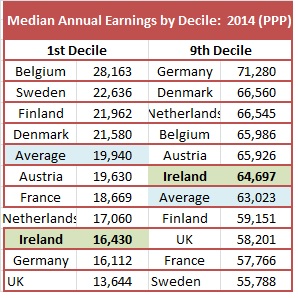

The median wage in the first decile (the lowest 10 percent income earners) falls even further behind the mean average: the median wage would need a 22 percent increase to reach the average. However, in the 9th decile (the second highest income group), the Irish median wage is actually above the average (3 percent).

So not only is the Irish private sector median wage low, it is skewered against the lower-paid.

This results in a highly unequal situation, though not the most unequal among our EU peer group. In terms of the ratio between the 9th and 1st decile, Ireland ranks 3rd from the bottom– ahead of the UK and Germany which comes in at the bottom (this should caution us about the alleged strong economic performance of Germany – it is built on precarious mini-jobs which now employs one-in-five employees).

Another concern is the rise in inequality.

In Ireland inequality jumped during the property boom period and has remained high since, significantly above the mean average of our peer group. The other EU countries remained on the whole relatively stable but this includes considerable increases in inequality in Germany and Netherlands.

The one downside to this data is that it doesn’t include employees’ full wage; in particular, the social wage. This is the portion of a workers’ wage that the employer pays into the Social Insurance or similar fund. From this fund, people can access free healthcare and enhanced pay-related in-work benefits (maternity benefit, illness benefit, etc.); that is, except in Ireland where the social wage is weak which results in low in-work benefits while forcing Irish workers to pay for goods and services on the private market which, in other countries, would be provided free or at below-market rates (e.g. GP care, prescription medicine, etc.).

Before we turn to tax and redistribution to reduce inequality let’s first consider policies at the workplace level since that is where inequality starts in the market economy. A big instrument in fighting inequality is workers’ ability to bargain collectively with their employers. I have discussed this in some detail so I won’t go into details here. But here’s this from the International Monetary Fund: which found that union membership and collective bargaining reduce economy-wide inequalities:

‘We find evidence that the erosion of labor market institutions is associated with the rise of income inequality . . . notably at the top of the income distribution . . . the decline in unionization is related to the rise of top income shares and less redistribution, while the erosion of minimum wages is correlated with considerable increases in overall inequality.’

A quick look at the CSO’s analysis of the distributional impact of public sector wages (which are collectively bargained) and private sector wages (which are largely not) shows the former has a more egalitarian wage structure with much smaller gap between the top and bottom income scales.

And the great thing about a collective bargaining strategy to tackle market inequality is that it doesn’t have a financial cost, unlike social protection programmes such as Family Income Supplement which effectively subsidises low wages.

We should be concerned about wage inequality, the inefficiencies it brings to the market economy and the corrosive effect it has on social cohesion. And we should translate that concern into giving men and women more power in the workplace. In this way, every workplace can start making a contribution to reducing inequality.

Leave a comment