It is curious how little debate there has been regarding Ireland’s banking system (apart from being scandalised by continuous scandals). The bank guarantee was brought in practically overnight while the Dail debate over the nationalisation of Anglo-Irish took only six hours. On the other side of the crisis there has been little debate over the privatisation of AIB and Permanent TSB. It seems that, when it comes to banking, we proceed by reflex.

Well, it’s not too late to start that debate. And it’s not too late to champion the cause of public banking. What are the advantages of public banking?

- First, while operating in a competitive commercially environment, it is not bound by short-term shareholder value. This frees the bank to engage in longer-term lending with patient capita

- Second, it can be rooted more locally with a mandate to lend into the productive economy – businesses and households; steering away from property and financial products.

- Third, through decentralisation it can engage in relationship-based lending based on knowledge of local markets and individual borrowers (advantaging SMEs), compared to transactional-based lending with its centralised and near-algorithmic approach.

- Fourth, public banks can be more amenable to political scrutiny and public accountability. A case in point is the current debate over the sale of mortgages to vulture funds.

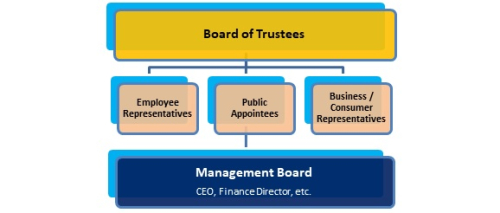

- Fifth and most importantly, would be its governance. The New Economics Foundation has proposed a trustee-based model to transform RBS into a local public bank. It would look like this.

The Board of Trustees – made up of employee, public appointees, and business and consumer representatives -would be responsible for overall policy while the Management Board would be charged with day-to-day implementation of that policy.There are other potential positives:

A public bank could be regionally based focussing on activities in the province they serve (e.g. Munster, Connaught). However, even within the province the banks could be branded in a way to show their commitment to the local areas (e.g. Bank of Kerry, Bank of Offaly, etc.).

The Central Bank has acknowledged continuing problems with ‘banking culture’ and if this 18th century pamphlet – Observations on, and a Short History of Irish Banks and Bankers – highlighted by Diarmaid Ferriter is anything to go by this is a long-term, probably endemic issue.

‘ . . . the abuse of the public confidence by bankers . . . the fatal calamities which have befallen this kingdom by the abuses of private banking . . . is there an evil, which can arise from the monopoly of money, which they have not produced? And how partial the little good which the community has reaped from them . . . the public can never rely upon the fidelity of bankers under the present regulations’.

Regulation can go far, but only so far. A public bank can provide competition with private banks on many grounds; in particular, ‘culture’, emphasising customer relations and service.

A re-investment in regions and communities could be undertaken by opening up branches – but doing so in imaginative ways. These branches could be one-stop shops housing post-offices, credit unions, MABS advisory centres, etc. This could be combined with community out-reach programmes such as local financial-education initiatives.

To provide for democratic input, customers could elect their consumer representatives on the Board of Trustees through postal ballots.

With public banking there is any number of initiatives and practices that could be considered to democratise this space.

Some would point out that we have had two banks under public ownership for years and nothing on this scale has emerged. That is true but the state, while ‘owning’ the banks, never acted like an owner. The state acted more like a concierge, opening the door and tipping their cap to any investor who happened to wander in. The day after these banks were brought into public ownership, the state plotted to get rid of them. We had public ownership but not public banking.

As to whether AIB or Permanent tsb should be the public bank of choice needs to be discussed. AIB might be a better fit given its size and reach throughout the country. O it may be decided that a smaller option – with the ability to grow – would be preferable; thus Permanent tsb. There are pluses and minuses with both; for instance, both banks have high levels of non-performing loans, but Permanent tsb’s profile is higher.

In both cases, consideration would have to be given to buying back the shares sold to private investors. This would be an upfront cost but one that could be paid for by removing the banks’ ability to carry forward losses and write them off their tax bills. This is another dubious cash subsidy to banks which are directly responsible for their own losses.

There is one more objection: if either bank remains in public hands, how would we recoup the bank bail-out subsidies which, in the case of AIB, is considerable (approximately €10 billion is still outstanding)? There are two responses:

- First, one may recoup the full-cost of the bail-out but there may be a bigger long-term price; namely, that selling the bank back to the same class of investors imbued with a short-termist perspective, the wider economic benefits would be lower than a public bank. That we cannot immediately monetise that difference doesn’t mean it wouldn’t have a real, negative impact.

- Second, the public bank would still be required to pay back the bail-out subsidies but over a longer-term, with the repayment constituting a type of ‘bail-out dividend’.

None of this is straight-forward nor open to easy answers. That is why we need a full and detailed debate. Let’s have the Oireachtas hearings, let’s examine models that work in Europe and the US. If there is an argument that privatising the two banks can still meet the goals of a public bank, let’s give it consideration.

The Left should not be silent on this or let the issue pass by default. If we’re talking about an economics of recovery, public banking could be a crucial element in that.

But most of all, let’s have the debate. For once the two public-owned banks are privatised, it will be even more difficult to argue the case for, never mind introduce, public banking.

Leave a comment