Of all the statements and comments from Budget 2017 my favourite comes from the Minister for Finance in his budget day speech:

‘We are a small and very open economy in a world that has more risks than usual. It makes sense to complete the task we set ourselves and get to a balanced budget. It makes sense to continue reducing our debt to much lower levels and to build our capacity to withstand shocks. It makes sense to avoid the mistakes of the past that could lead to overheating our economy. It is an uncertain world full of risk and now is not the time to move away from the prudent and sensible fiscal policy we have been following.’

It’s all there: small open economy, more risks than usual, capacity to withstand shocks, avoid past mistakes, world full of risk and prudent fiscal policy. So what is the Government doing? It is eroding the tax base while at the same time relying on a potentially new tax revenue bubble. So much for avoiding the mistakes of the past.

Since 2012 corporate tax revenue has increased by 92 percent; for all other taxes it is just 33 percent. Corporate tax revenue increases has made up over a quarter of total tax revenue increases. And in 2015 ten companies accounted for over 40 percent of all corporate tax revenue. Revenue estimates that of the €6.9 billion in corporate tax revenue, €2.8 billion came from these 10 companies. And this proportion is growing.

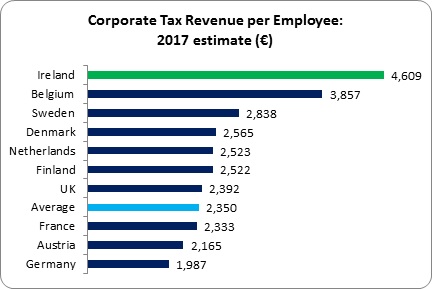

Given that our national accounts can no longer be used for comparative purposes we will have to resort to other measurements. So how’s this one – the amount of corporate tax revenue per employee.

Looking at the other Northern and Central European economies, we find our corporate tax haul per employee is considerable – twice as much as the average. That seems to describe the situation fairly. Even using our national accounts, corporate tax revenue makes up 3.9 percent of GDP; for the other countries it is 2.5 percent.

This is a highly dangerous place to be – so much of our tax revenue reliant on just a handful of companies. These are probably all US multi-nationals.

- What happens if the US Congress changes the tax laws such as allowing companies to repatriate their overseas profits at below current tax levels?

- What happens if the EU Commission is eventually successful in implementing a Common Consolidate Corporate Tax Base which would reduce the amount of profits multi-nationals could shift into Ireland?

- What happens if there is slump in the sectors that these companies operate in, reducing profits?

- What happens if these companies change their tax strategies or start to relocate some of their tax-related functions to even more ‘hospitable’ countries?

These are the risks that the world is full of, as the Finance Minister might put it. These are all contingencies that are pretty much outside our control. It’s not a matter of refusing to take in this tax revenue but it is a matter of balancing the risks that accompanies this revenue. Yet, the Government seems intent on ignoring the risks and repeating past mistakes – in particular, the mistake made prior to the crash: eroding the tax base while relying on, in this instance, property-related tax revenue.

In Budget 2017 the Government cut USC (again) – a highly efficient tax which raises considerable revenue at low rates since it has a very broad base. In the last three budgets the Government has cut personal taxation by €2.1 billion (or 10 percent of the personal tax take this year) with a commitment to cut a further €3 billion or more. And this doesn’t count cuts in inheritance and property tax (the latter due to the postponement of revaluation to 2019).

This is not a good place to be. Far better to lay down a long-term fiscal plan which assumes a bubble – or at least an above average tax take from the corporate sector. From that, we could build a more sustainable revenue base (broaden the base). Anything above and beyond that could be used for once-off expenditure. How about building houses? Or equity participation in newly established or expanding indigenous firms? Even spending on capital investment in the short-term with a plan to reduce reliance on this bubble money in the medium-term; there’s nothing to suggest that we have such a plan.

We could be sleep-walking into another crisis; maybe not as acute or dramatic as our last crash. But if we ignore the signs we’ll happily head full-speed down the road naively believing there’s no obstacle around the bend.

Prudence, indeed.

Leave a comment