The run-up to the budget is my favourite time of the year. Commentary on Irish taxation tends towards the deliciously deceiving, hilariously spurious or just plain weird. And the Irish Taxation Institute’s ‘Perspectives on Ireland’s Personal Tax System’ doesn’t disappoint. Let’s look at three arguments contained in that report.

Marginal Tax Rates

We constantly hear that ‘high Irish taxes are a disincentive to employment and undermine competitiveness’. Usually, this refers to high marginal tax rates.

The marginal tax rate is the tax you pay on the next euro you earn. You’re on €30,000. The next Euro you earn will be taxed at 29.5 percent (20 percent income tax, 5.5 percent USC and 4 percent PRSI). How do marginal tax rates compare in the EU-15?

Let’s walk through this crowded table. On low incomes, two-thirds of the average wage, almost all countries have a higher marginal tax rate than Ireland. Think on this – if high marginal tax rates were a disincentive, than all those other countries should be plagued by unemployment and loss of competitiveness. Oh, yeah, that characterises Germany alright – they have a marginal tax rate of 47.1 percent compared to our 31 percent. They must be close to the bailout zone.

Ireland rises up the table at 100 percent of average wage but that ol’ uncompetitive Germany is still higher. After that, Ireland starts falling down the table. So we have a situation where our marginal tax rates are very low, relatively high and then middling while countries with strong economic and social performance rank higher than us. The relationship between marginal tax rates and performance is not apparent.

And there’s this: French and Swedish workers face much lower marginal tax rates at the average wage. Yet they are high-taxed economies. So how does that work? The OECD shows that French employers pay a marginal PRSI rate of 37.9 percent while Swedish employers pay 31.4 percent; Irish employers pay 10.8 percent. Most EU employers pay a far larger share of the total tax on labour. If the Institute is suggesting we treble employers’ PRSI to facilitate an increase in the standard rate tax threshold, I’m all ears.

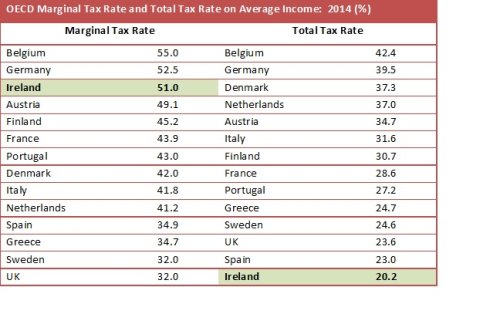

But marginal tax rates are not the full story. One peculiar aspect of the Irish tax system is that while average income workers face high marginal tax rates, their total tax rate is the lowest in the EU-15. Remember – the marginal tax rate looks at the tax you pay on the next Euro you earn. The total tax rate is the actual amount of tax you pay as a percentage of your income. Check this out.

Irish average income earners pay a relatively high marginal tax rate. But when it comes to the actual amount of tax we pay, Ireland is at the bottom of the table – even below much poorer countries like Portugal and Greece. We’d have to double the amount of tax on average earners to reach German levels. The lesson you draw depends on perspective. A proper way to look at this is to take all factors into account.

Let’s leave this section with a comment from Prof. Alan Barrett of the ESRI at Committee on Budget Oversight:

‘It is sometimes argued that high tax rates are a disincentive to work. At some point this is probably true but . . . is there evidence to suggest that the current tax rates are leading to widespread withdrawals from the labour market. The most recent figures show that employment increased by 56,000 in the year ending quarter 2, 2016, or almost 3%. Evidence on this issue should be gathered in a more sophisticated manner but even this simple approach raises the question of whether tax is acting as a significant disincentive to work. It could be the case that child care is a greater disincentive. If this is true, then a greater effect on labour supply could be achieved through child care subsidies as opposed to income tax cuts, including USC cuts.’

Indeed.

Selecting Your Data

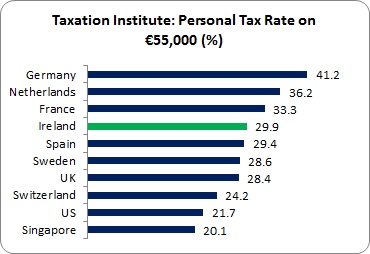

The Taxation Institute claims the Irish tax rate (the actual amount paid as a percentage of income) on higher income groups is high relative to other countries. But they are fairly selective with the countries they compare Ireland with.

This shows Ireland at the upper end of the table. But what of the countries they’re using as comparisons?

- Yes, Ireland is ahead of Sweden but as mentioned above, the Swedish rate is subsidised by high rates on employers.

- Yes, Ireland is ahead of Switzerland but that country has a strong wealth tax; if Ireland transplanted that tax here it would raise over €2 billion. That would subsidise a lot of tax cuts and spending increases.

- Yes, Ireland is higher than the US but do we really want to compare ourselves with a highly-unequal, high poverty-rate country with a feeble social net and crumbling infrastructure?

- And, yes, Ireland is higher than Singapore. But Singapore?

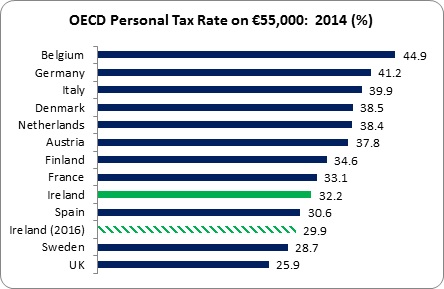

Here’s another comparison – based on OECD data for the EU-15 countries (no data for Portugal and Greece).

This puts a different perspective on things. Ireland is well below most other EU countries; especially poor ol’ Germany.

The Institute also claims that:

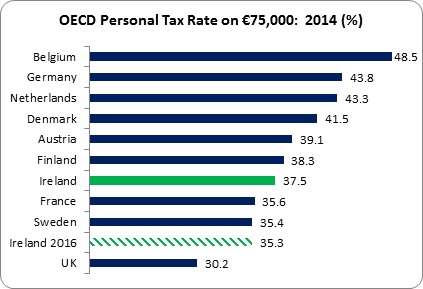

‘By the time you get to €75,000 we are a high tax country by international comparison . . .’

In their table we rank fourth, using the same comparative countries as above. However, when we turn to a comparison with other EU-15 countries (data not available for the Mediterranean countries) a different picture emerges.

We rank below a number of other countries and in the last two years, the tax rate has fallen. Can this really be called ‘too high’?

Number Mongering

The Taxation Institute comes up with a peculiar series of measurements. Here are some samples.

- A worker on €35,000 earns 1.4 times the amount of a person on €25,000 and pays 1.9 times the amount of tax.

- A worker on €75,000 earns 3 times the amount of a person on €25,000 and pays almost 8 times the amount of tax.

- A worker on €75,000 earns 2.1 times the amount of a person on €35,000 and pays over 4 times the amount of tax.

- A worker on €100,000 earns 5.6 times the amount of a person on €18,000 and pays almost 66 times the amount of tax.

And so on. I have no idea what this means. The Taxation Institute may be trying to tell us that Ireland’s taxation is too progressive and is undermining our competitiveness. But some of their comparisons make no sense. The person on €100,000 is compared to a worker earning below the minimum wage (note: if the minimum wage was increased to the Living Wage, then instead of the person on €100,000 paying 66 times the amount of tax, this would be reduced to 14 times; maybe the Taxation Institute is making an indirect plea for a Living Wage).

How do we make sense of this statistical mush? Let’s go to the Taxation Institute for help:

‘Progressivity is about proportionality not about absolute Euro amounts.’

Fair enough. Let’s look at the ‘A worker on €35,000 earns 1.4 times the amount of a person on €25,000 and pays 1.9 times the amount of tax’ formulation. This is true in absolute Euro amounts. But what about proportionality?

A worker earning €25,000 pays 13.5 percent in tax. A worker earning €35,000 pays 18.7 percent in tax. When the percentage of tax is expressed as a ratio, the higher earner pays 1.4 times much tax as the lower earner – the same ratio as their gross income.

And what about this: a worker €75,000 earns 3 times the amount of a person on €25,000 but pays only 2.8 times the amount of tax, expressed as a percentage of income. Does this mean our income tax system is actually regressive? No, it means nothing at all, just like the Institute’s formulations.

This is mere number-mongering, devising measurements that purport to tell us something but actually tell us nothing. There are all sorts of number-play we can come up with to fit any conclusion we want. For instance:

If you take the Institutes tax/income ratio between those earning €25,000 and €35,000 (1.4), multiply it by the number of days we pay taxes (365), add the number of all Ministers (33) and add the number of Oireachtas members who approve tax measures (118) – you almost get the number 666.

The Irish personal taxation system has been marked by the devil. QED.

* * *

Let’s quickly bottom-line all this. There is an underlying assumption that tax cuts can buy higher living standards. Can tax cuts make childcare affordable; reduce rents, spare us from congestion; eliminate A&E over-crowding; expand educational opportunities; care for elderly relations; clean up rubbish piles; equip the Gardai properly; lift people out of poverty and deprivation; reduce the costs of medicine – you get the picture. The goods and services that provide security, opportunity and prosperity require investment, not tax cuts.

This is not to ignore problems in the actual tax code. The entry level at the top tax rate is too low. But raising it would be extremely expensive. Increasing the threshold to €40,000 would cost €1.1 billion. So why not introduce a 30 percent tax rate up to this level? This would cut the cost in half and phasing it in over a number of years would limit the annual cost. Or, just scrap income tax altogether and replace it with a USC style-tax; that would really reduce marginal tax rates (as suggested here).

But cutting taxes is not the priority. Investment is – social, economic and infrastructural. And if you are worried about our competitiveness, be assured. Countries with higher personal and corporate tax, higher employers’ social insurance, and stronger labour regulations – they all are ranked much higher than Ireland in the business competitiveness stakes (as you can read here).

Ultimately, we need an informed and evidence-based debate on taxation. But this is budget season. So we’ll have to wait awhile.

Leave a comment