Education, the skill-base of the labour force, human capital: this is the key to growth in the future. This is the key to increasing people’s life-chances. Michael Noonan referred to accepting the EU’s ruling on Apple as ‘eating the seed potatoes’. Well, under-resourcing education is tantamount to gorging. We think we’re ‘saving money’ in the short-term but we are actually fleecing our collective future.

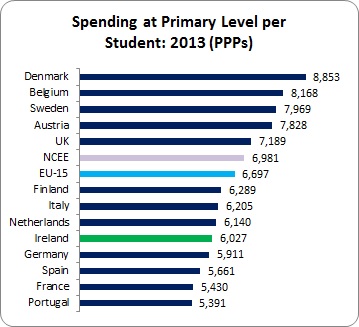

Unfortunately, Ireland under-resources education; considerably so in comparison with other EU countries. We can no longer use expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP as a guideline since our national accounts are no longer fit for purpose. But we can measure educational expenditure per full-time equivalent student. This is how Ireland compares using mean averages.

Ireland lags in the primary education funding tables (no data for Italy and Luxembourg). We’d have to increase spending by 11 percent to reach the EU-15 level and 16 percent to reach the average of our peer group – Northern and Central European economies (excluding the poorer Mediterranean countries). If we wanted to reach the level of the top spender – Denmark – we’d have to increase spending by 47 percent.

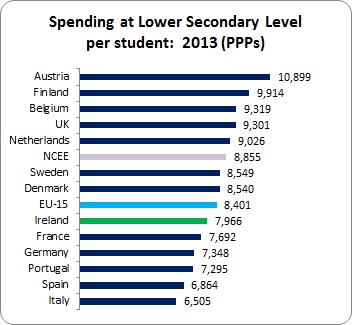

At the lower secondary level (no data for Luxembourg), the relatively low level of spending is repeated but not as extreme. Ireland would have to increase spending by 5 percent to reach the EU-15 level and 11 percent to reach the average of other NCEEs. To reach the top – Austria – we’d have to increase spending by 37 percent.

At the upper and post-secondary levels (excluding third level), Ireland fares well. Spending is above both the EU-15 average (7 percent) and the average of other NCEEs (4 percent). So in this sector we are slightly above average.

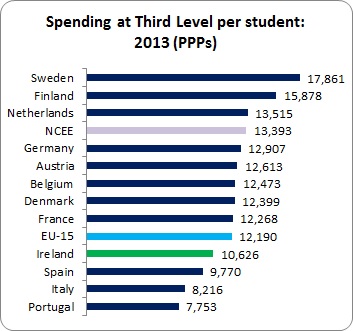

However, when we turn to third level, Ireland takes a big dive.

It is at this level that shows Ireland a low education spender (no data for the UK and Luxembourg). Ireland would have to increase spending by 15 percent and 26 percent to reach the average of EU-15 and NCEE countries respectively. To reach the top – Sweden – we’d have to increase spending by a massive 68 percent.

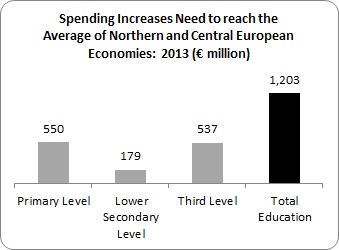

In overall spending on education per student in public institutions, Ireland lags in the lower half of the table, trailing the averages of both the EU-15 and NCEE. What does all this mean in Euros and cents? The total expenditure data is taken from Eurostat which may categorise educational levels differently than the Government’s public service estimates (which in 2013 doesn’t distinguish between levels).

In 2013 we would have to increase overall education spending by €1.2 billion to reach the average of Northern and Central European economies. The biggest increases required are at primary and third level – over half a billion Euros in each sector. And that’s just to reach the average.

That was in 2013. Between then and 2016, overall spending increased by €286 million or about 1 percent annually; and during this period the number of students rose as well. So it is probably the case that Ireland’s position hasn’t changed much.

Imagine the impact of such increases: more teachers, resources, targeted programmes – and an end to precariousness in the education sector.

There are two general observations:

First, expenditure levels don’t speak to the efficiency of the spending – the ol’ value-for-money thing. A country may be spend a lot but their outcomes may not reflect that; other countries may spend less but achieve better outcomes. This requires a more detailed examination.

Second, there are particular factors to be taken into account for Ireland which may point to the need for even more expenditure in the short-term over average European levels: lower population density which requires more physical infrastructure; need for higher capital investment to accommodate rising youth population; and repairing the damage of the austerity years (Eurostat data shows a cut of nearly 15 percent, or €1.4 billion between 2008 and 2013).

There is another general point. Education expenditure comes from ‘general taxation’, a phrase which is increasingly used in the debate. The problem is that this phrase is rarely accompanied with an estimate of how much general taxation would have to rise to meet this expenditure, never mind what tax measures one would use.

For instance, if the Government decided to increase educational expenditure to our peer group average over a five-year period, it would amount to €250 million each year (not counting the ‘particular factors’ mentioned above). In 2017, this would take up 25 percent of the fiscal space. Now let’s talk about all the other areas where spending increases are needed (economic investment, water & waste, social protection, health, and all the other areas – and, of course, social and affordable housing).

In short, if we want to have an education sector worthy of its name, on a par with other countries (at least in funding) we will have to pay for it. But it would be a sound investment.

Call it – planting seed potatoes.

Leave a comment