The Nordic model, or at least the public services and income supports associated with that model, has got some airing largely owing to supportive comments made by the TDs who launched the new Social Democrats. Good. There is much to learn from the Nordic model and its emphasis on social solidarity and universalism; an emphasis which produces higher equality, less poverty and deprivation and more prosperous economies and societies.

But there’s a catch: there is little appreciation of the resources the Nordic model devotes to public services and income supports. It is substantial, well above Irish levels (light years above) with very high levels of taxation and, in particular, the social wage (employers’ PRSI) and indirect taxation.

Let’s go through some of the main spending and tax features to see just how much of a challenge we would face in moving towards this model.

Public Services

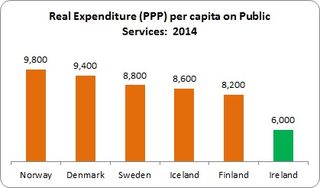

To say that the Nordic model spends a lot on public services is a massive under-statement. Remember, this only refers to public services; it doesn’t include social protection payments (e.g. pensions, child benefit, unemployment benefit, etc.).

Ireland trails badly in expenditure on public services. In 2014, Ireland spent €30.5 billion on public services (all Irish comparative data uses a hybrid-GDP, adjusting for multi-national accountancy practices). What kind of increases would be necessary to reach the levels of expenditure in other Nordic countries?

Ireland trails badly in expenditure on public services. In 2014, Ireland spent €30.5 billion on public services (all Irish comparative data uses a hybrid-GDP, adjusting for multi-national accountancy practices). What kind of increases would be necessary to reach the levels of expenditure in other Nordic countries?

Finland: we’d have to increase spending by €11.5 billion, or 37 percent, to reach their level – and Finland is the low-spend of all the Nordic countries.

Iceland and Sweden: Ireland would to increase spending between €13.6 and €14.7 billion to reach their levels, or between 43 and 47 percent.

Denmark and Norway: to reach these stratospheric levels, spending would to increase between €17.8 and €20 billion.

On average, public service spending in Ireland would have to increase by 50 percent – or approximately €15 billion to reach Nordic levels. That is an ambitious agenda.

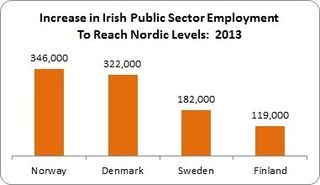

Public Sector Employment

Given these high levels of expenditure, it is not surprising these countries have high levels of public sector employment. Ireland has approximately 370,000 employees in the public sector (including public enterprises or Government corporations). This is 17.4 percent of the workforce. In the Nordic countries that figure is much much higher.

Given these high levels of expenditure, it is not surprising these countries have high levels of public sector employment. Ireland has approximately 370,000 employees in the public sector (including public enterprises or Government corporations). This is 17.4 percent of the workforce. In the Nordic countries that figure is much much higher.

We’d have to double public sector employment to reach Norwegian and Danish levels – approximately 350,000 more public sector employees. To reach Swedish levels we’d have to increase employment by 50 percent, or 182,000. Compared to ‘low-spending’ Finland we’d have to increase employment by nearly a third, or 119,000.

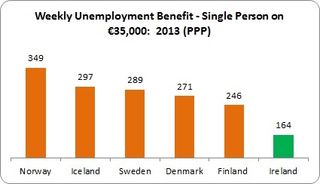

Unemployment Benefit

Not only is spending on public services generous, Nordic levels of income support are similarly substantial. Here are the levels of unemployment benefit a worker on €35,000 would receive if they were suddenly jobless. They are enumerated in purchasing power parities.

Again, Ireland trails badly. Irish unemployment benefit for a single person is €188 weekly. To put this in nominal Euros perspective:

Again, Ireland trails badly. Irish unemployment benefit for a single person is €188 weekly. To put this in nominal Euros perspective:

Norway: Irish levels would have to rise to €400 per week, or more than double the current payments

Denmark, Sweden and Iceland: Irish levels would have to rise to between €310 and €340 per week, or 65 to 81 percent higher

Finland: Irish levels would have to rise to €282 per week, or 50 percent higher

These rates will be phased out over a year to 18 months and, so, fall to a lower level. But this is the system of pay-related benefit. Imagine if you were an average paid worker made unemployed. You’d get €188 from the dole. If you lived in a Nordic country you’d get, on average €322 per week for the first year. Your living standards wouldn’t crash, the economy would benefit from your continued demand (automatic stabiliser) and you wouldn’t have to rush out and grab the first job, regardless of whether it matched your skill or life-expectation.

Supports for Elderly

Here is another difference between Ireland and the Nordics. This is the Eurostat category for old age expenditure which includes pensions, in-kind supports (e.g. home help, subsidised equipment such as walking frames), recreation and leisure supports, and specialist medical care. It doesn’t include general hospital costs.

Spending in Sweden and Finland on each elderly person is nearly doubled that of Ireland, with Norway close behind. The Danes spend nearly 40 percent more. Iceland looks strange – at almost half that of Irish levels. But this is due to their pension system which is based on mandatory occupational pension provision – not social insurance. This means payments are not attributed to state expenditure. But don’t worry about elderly provision in Iceland – they have the lowest percentage of severe material deprivation among the elderly in all of Europe: only 0.2 percent. In Ireland, it is 3.6 percent.

Spending in Sweden and Finland on each elderly person is nearly doubled that of Ireland, with Norway close behind. The Danes spend nearly 40 percent more. Iceland looks strange – at almost half that of Irish levels. But this is due to their pension system which is based on mandatory occupational pension provision – not social insurance. This means payments are not attributed to state expenditure. But don’t worry about elderly provision in Iceland – they have the lowest percentage of severe material deprivation among the elderly in all of Europe: only 0.2 percent. In Ireland, it is 3.6 percent.

Paying for These Services

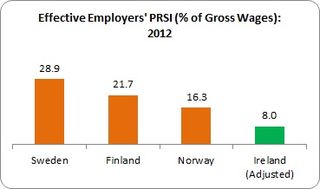

My, oh, my. How do the Nordics pay for all this? They are, of course, very highly-taxed economies but not in the way that is discussed in the popular debate.

The biggest difference with Ireland is the social wage, or employers’ social insurance (PRSI). Nordic employers pay extremely high levels of PRSI to fund public services and income supports.

Swedish employers pay nearly four times the amount of PRSI as Irish employers. Finnish employers pay close to three times the Irish levels while Norwegian employers pay more than double. There is no data for Iceland and Denmark doesn’t have a social insurance system (see below). If Irish employers paid the same rate as other countries this is the revenue it would raise:

Swedish employers pay nearly four times the amount of PRSI as Irish employers. Finnish employers pay close to three times the Irish levels while Norwegian employers pay more than double. There is no data for Iceland and Denmark doesn’t have a social insurance system (see below). If Irish employers paid the same rate as other countries this is the revenue it would raise:

Swedish levels: Irish revenue would increase by €13.6 billion

Finnish levels: Irish revenue would increase by €8.9 billion

Norwegian levels: Irish revenue would increase by €5.4 billion. But Norway takes a huge chunk of revenue through a much higher level of corporate tax (it raises nearly four times the amount raised in Ireland – one of the benefits of having natural resources like oil under public control).

Let’s be clear: there is no Nordic model without very high levels of employers’ PRSI. In Ireland we would have to at least double employers’ PRSI and, more likely, increase it close to three times. Now that is an economic and political challenge (business organisations are going spare having to pay 50 cents an hour more for minimum wage workers – imagine their response to a doubling of their social insurance?).

Another significant difference is indirect tax – VAT and excise. Nordic countries raise significantly higher revenue through this channel than Ireland.

Ireland is close to Icelandic levels. However, we would have to raise between €3.2 and €4.4 billion in VAT and excise to reach Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish levels. To reach Danish levels we would have to raise an additional €6 billion, or 40 percent more. These levels of indirect tax are highly regressive. But the organisations of public services and income supports means they are redirected back into supporting low and average income earners.

Ireland is close to Icelandic levels. However, we would have to raise between €3.2 and €4.4 billion in VAT and excise to reach Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish levels. To reach Danish levels we would have to raise an additional €6 billion, or 40 percent more. These levels of indirect tax are highly regressive. But the organisations of public services and income supports means they are redirected back into supporting low and average income earners.

And personal taxation? Actually, Irish levels of employee taxation (Income tax, USC, PRSI) are already close to Nordic levels. We found a similar situation with France.

Personal taxation on employees’ income would have to rise by €1.4 to €2.5 billion to reach Nordic levels (this was in 2012; the gap has most likely narrowed since then). This may seem like a lot but reduction in regressive tax expenditures and keeping indexation of tax thresholds below the rate of wage increases should see Irish personal tax rates rising to Nordic levels over the medium term without increasing rates.

[Note on Denmark: Denmark doesn’t have a social insurance system. Instead, it relies heavily on personal taxation. In Denmark, the effective rate of personal taxation on employee income is 37 percent compared to Ireland’s 24 percent. To reach Danish levels, personal taxation would have to rise by nearly 60 percent, or over €9 billion. They can achieve this through much higher wage levels but this is countered by high prices and high indirect taxes. It can work for Denmark. However, it is probably not a model for Ireland to follow.]

Some might respond that these comparisons aren’t fair; that the Nordic countries are wealthier – that is, they generate more income as measured by GDP. Well, actually, no.

Irish hybrid-GDP is well ahead of Finnish levels and approximately equal to the other Nordic countries (apart from Norway with its wealth of oil revenue). The reason we don’t have public service and social protection expenditure at the level of Nordic countries is not that we are poorer; it’s a policy choice.

Irish hybrid-GDP is well ahead of Finnish levels and approximately equal to the other Nordic countries (apart from Norway with its wealth of oil revenue). The reason we don’t have public service and social protection expenditure at the level of Nordic countries is not that we are poorer; it’s a policy choice.

So what have we got? To follow a Nordic strategy in Ireland would mean a substantial increase in expenditure on public services and public sector employment. It would also require substantially increased expenditure on social protection and income supports.

But to achieve this would require doubling or trebling employers’ social insurance rates and substantially increasing indirect taxes (if we don’t follow the high personal tax model of Denmark).

But these tax and spend issues are only one part of the Nordic model. Another important feature is the labour market; in particular, the strong level of labour rights and collective bargaining coverage. Workers’ rights and dense layers of employee participation are an essential ingredient to building a consensus over high levels of taxation and expenditure as well as a very high level of enterprise performance.

To pursue Northern dreams will require long-term and sophisticated strategies designed to win people over to a different vision about how we organise taxation, expenditure and the economy. It will also require taking on hostile corporate forces and right-wing political parties. It will require creative thinking, persuasive arguments and a determined political will.

Let’s hope this gets traction.

Leave a comment