In 2014, GDP increased by 4.8 percent – as often said, the fastest growing economy in Europe. In 2014, employment increased by 40,000. In 2014, the recovery started.

In 2014, living standards fell even further behind the EU-15 average.

Eurostat measures living standards through actual individual consumption. Unlike private consumption, or consumer spending, actual individual consumption

‘ . . . encompasses consumer goods and services purchased directly by households, as well as services provided by non-profit institutions and the government for individual consumption (e.g., health and education services).’

It, therefore, measures consumption not only of goods and services, but public services provided by the government. As Eurostat states:

‘Although GDP per capita is an important and widely used indicator of countries’ level of economic welfare, (actual individual) consumption per capita may be more useful for comparing the relative welfare of consumers across various countries.’

In short, actual individual consumption can be treated a proxy for living standards. So what is the relative welfare of consumers (i.e. everyone) across Europe? The following captures the relationship of real (after inflation) living standards in purchasing power parities between EU-15 countries and the EU-15 average.

We can see that Ireland is in the bottom half of the table – 15 percent below the average. Our living standards are closer to Greece and Portugal than it is to the EU-15 average and the majority of countries.

Unsurprisingly, our living standards have been falling since we entered the recession. In 2008, Ireland stood at 95 – still below the EU-15 average and most other EU-15 countries. During Fianna Fail’s reign, it fell six points to 89. Under this government, it has fallen a further four points to 85.

Last year our living standards fell – from 87 to 85. This coincided with all the good new stats – GDP and GNP growth, employment, exports, etc. This may help explain that oft-asked question: if the economy is growing, why don’t I feel it?

It should be stressed that this is a relative measurement – relative to the EU-15 average. In real terms (after inflation), Irish actual individual consumption per capita increased, but only slightly, while growth in the EU-15 was far higher.

Note the contrast: Belgium and France saw substantial increases in living standards even though GDP growth in 2014 was 1.1 and 0.2 percent respectively. Irish living standards barely grew, even though it had a growth rate of four times that of the two countries.

There are a number of potential explanations for this:

First, the rise in living standards lag headline GDP growth. However, during this period we are led to believe that employment rose substantially; surely, this should have resulted in a larger impact than the above chart shows.

Second, much of our GDP growth is illusory. Considerable commentary and analysis certainly points to this.

Third, Ireland has difficulty translating growth into living standards. At this early stage in our recovery, it might be premature to make this conclusion but early returns are not promising.

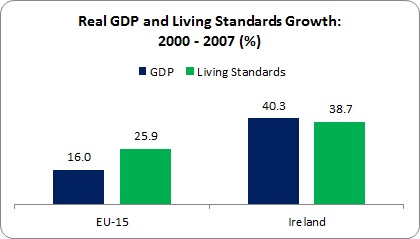

There’s is a larger discussion this should provoke. Is there something wrong with the Irish economic and social model? Is the Irish model inefficient when it comes to translating economic growth into living standards? The following tracks this between 2000 and 2007.

As seen, in the seven years prior to the crash, Irish GDP increased by more than twice the rate of the EU-15. However, our living standards didn’t grow by nearly this rate. Put another way:

- In the EU-15, every 1 percent growth in GDP translated into a growth of 1.6 percent in living standards.

- In Ireland, every 1 percent growth in GDP translated into 0.9 percent growth in living standards

Again, we have to be cautious about the Irish numbers – this was during a period of speculative boom. Nonetheless, we should be asking if our inability to efficiently translate GDP growth into living standards is due to our low-tax, low-spend, low-service, low-investment model? That’s a big question which we should start debating now.

It should be emphasized: actual individual consumption is only a proxy for living standards. There is no one headline graph, no single killer stat that can fully capture the totality of living standards. The same holds for measurements like poverty or social exclusion. All statistics come with health warnings and caveats since any particular statistic may only capture part of the picture or do so only approximately. Instead, we have to bring together several pieces of data.

Nonetheless, actual individual consumption is a robust measurement. And it shows Irish living standards, or the relative welfare of consumers, are still falling relative to the EU-15 average.

And if we take this seriously, it might lead us to ask whether our economic and social model is fit for purpose.

Leave a comment