How do EU countries manage to provide better public services and income supports than us? And are the Irish willing to pay for European-style public services (the implication being we are not). These were the two questions posed by the Claire Byrne Live show which compared life in France with our lives here. It was both provocative and frustrating; frustrating because it did not answer the first question. Had it done so, we would have realised the second question is irrelevant.

Provocatively, we learned that in France:

- Children receive full-time education from the age of three, totally free

- A visit to the GP costs €7 and the waiting times for medical procedures can be measured in days – not months or years

- If you become unemployed, you get 80 percent of your last wage in unemployment benefit for up to two years.

In other words, the French social model is far, far advanced compared to ours.

How do they do they achieve this? Do they tax their citizens more? The programme provided a couple of statistics in a video introduction that should have alerted the discussion. They compared a French two-earner household with an Irish one – both on €80,000. The Irish household paid higher personal taxes (income tax, USC, PRSI).

The second stat showed French government spending at 57 percent of GDP; Irish government spending is well below that at 40 percent. So, if Irish personal taxes are higher, but spending is much lower – well, somewhere in there is the answer. Let’s see if we can find it with the help of Eurostat and the EU’s Ameco database.

When it comes to personal taxation on employees and household consumption tax (VAT and Excise), Ireland and France are pretty close with both trailing the EU average. So the reason can’t be found here.

What about corporation tax? The effective French corporate tax rate in 2012 was 32.1 percent; the second highest in the EU. The Irish rate is a lowly 8.5 percent. But, in actual fact, this can’t explain the disparity in expenditure on public services and income support. While the Irish rate is nearly four times less than the French one, we receive more corporate tax revenue than France. Corporate tax revenue in Ireland makes up 2.3 percent of GDP; in France, it makes up 2.2 percent. How can this be?

Simple. Companies transfer billions of Euros in profits generated in other countries and ‘book’ them here (i.e. pretend that they are ‘Irish’ profits). This increases the volume of profits taxed in the country and, therefore, the same amount of revenue in corporate tax can be raised.

All this to say, the level of corporate tax revenue cannot explain the disparity between France and Ireland.

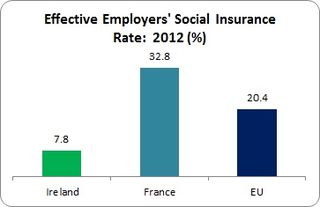

So what does? Employers’ social insurance or the ‘social wage’. Employers’ social insurance is part of an employee’s compensation package. It is that part of the employees’ wage that is paid into a social insurance fund from which we obtain services for free or at below-market rates – just like France’s free early childhood care/education and GP visits for €7.

The employees’ social insurance gap between Ireland and France is substantial.

Ireland’s social wage, or employers’ PRSI, is the lowest in the entire EU (save for Denmark which doesn’t have a social insurance system). It would have to quadruple to reach the French level which is the second highest in the EU.

Ireland’s social wage, or employers’ PRSI, is the lowest in the entire EU (save for Denmark which doesn’t have a social insurance system). It would have to quadruple to reach the French level which is the second highest in the EU.

Let’s put Euros and cents on this. In 2012, Irish employers’ PRSI raised €5 billion. If it were at French levels, it would have raised €21 billion. That’s €16 billion more than what Irish employers pay now. Imagine the public services and social protection income supports you could provide with an additional €16 billion.

Of course, France is an outlier when it comes to employers’ social insurance – it is well above the EU average. And because they have an older age demographic, their expenditure has to be higher than ours. Nonetheless, if Irish employers’ PRSI were increased to just the EU average, it would raise an additional €8 billion – still a hefty sum for investment in our social infrastructure.

There is little appreciation of the role of employers’ social insurance in European taxation structures. In many countries, employers’ PRSI raises more than personal taxation on employees: Estonia, France, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Italy, Slovakia, Cyprus, Spain and Sweden. In France, employers’ social insurance raises €266 billion; personal taxation on employees raises €175 billion. In other words, employers’ social insurance raises 51 percent more than employees’ taxes.

In Ireland, the situation is radically reversed. Employers’ PRSI raises €5 billion; personal taxes on employees raise €15 billion; employers’ PRSI raises 65 percent less than employees’ taxes.

So to answer the questions posed by the Claire Byrne Live programme: in other EU countries, higher levels of public services and social protection income support are funded by much, much higher levels of employers’ social insurance, or social wages.

As to whether Irish people should be willing to pay more for public services – my response is: why? Irish workers are already paying – through labour and consumption taxes – at average EU levels. But they are not getting EU level of public services and social protection support. Why?

Because Irish employers are not making an equivalent contribution that their European counterparts are making. In addition to benefitting from ultra-low corporate tax rates, they benefit from ultra-low social insurance. Workers are already paying their fair share; employers are not. There are two things that follow from this:

- Under the current regime, there is little chance of achieving European level of public services and income supports if the entire cost is imposed upon workers – whether through personal taxation or consumption taxes.

- We will not achieve those European services and income supports unless the social wage, or employers’ PRSI, is substantially increased.

It’s that simple.

Leave a comment