Are you getting tired of unsubstantiated claims that social

protection payments are a disincentive to taking up a job? Me, too.

These assertions pass for informed commentary on the unemployment

crisis, using crude calculations and even cruder assumptions about social

behaviour. Let’s throw some light on

this dismal debate.

It is claimed that welfare payments make up too high a

proportion of take-home pay from work, and that this is stopping people from

taking up work. This, in turn, is

helping to maintain high unemployment. This

is called the ‘replacement rate’. If you

earn €100 and social protection payments are €60, the replacement rate is 60

percent. If the replacement rate is too high, you get

disincentives. When this happens, you

have to do something (this usually means cutting social protection payments) in

order to reduce the replacement ratio.

Let’s examine the replacement rates from two years – 2012 and

2007. With the help of the Citizens

Information Board’s budget summaries and the TaxCalc calculator I will focus on a two-adult

household with three children since the main complaints re: welfare disincentives

usually focus on large households. We

will compare them with the household take-home pay on the minimum wage, along

with average take-home pay in the retail sector and the overall economy (one

work-income earner).

The replacement rates were higher in 2007 than they were in

2012. With average earnings, social

protection payments made up 66 percent of take-home pay in 2007; in 2012 they

made up 63 percent. There were similar

falls in the replacement rate for average retail earnings and the minimum

wage.

For all households, income from Child Benefit fell. Average work income flat-lined but net

take-home pay fell owing to higher taxation.

This was compensated by increases in the Family Income Supplement. Social Protection payments, excluding Child

Benefit, increased but this was mostly due to Child Dependent Allowances (adult

rates only increased only marginally).

Put those all through the mix and we find the replacement rates

falling.

The above excludes housing subsidies – notably, rent

supplement which creates real traps in the system. However, were we to include them the

replacement rate in 2007 would be even higher than in 2012. This is because the average rent supplement

paid has fallen considerably. In

2007 the average rent supplement paid was €6,554. In 2012, it had fallen to €4,819 – a fall of

over 26 percent. In addition, it should

be noted that only 11 to 12 percent of the unemployed received rent supplement,

so we’re talking about a small proportion.

.

So if the welfare disincentive argument is valid – that ‘high’

social protection payments are preventing people from taking up work –we should

have seen this problem in 2007 since replacement rates were higher than they

were last year. We should have seen a

situation of relatively high unemployment and vacancies going unfilled. But what do we find instead?

- Unemployment rate in 2007:

4.7 percent - Unemployment rate in 2012:

14.7 percent

In 2007 the long-term unemployment rate was 1.4 percent; in

2012 it was over 9 percent.

So when the replacement rate was higher we nearly had a full

employment economy with one of the lowest long-term unemployment rates in the

EU. Now that replacement rates are lower

we have massive unemployment, both short and long-term.

One could be cheeky and suggest an alternative co-relation –

the higher the replacement rate, the lower the unemployment rate; therefore, to

create incentives to work we should increase social protection payments. But that would be as invalid as the opposite

claim. There are far more important factors

in creating high unemployment – namely, the lack of jobs. We’ll look at this below but first let’s do

some international comparisons.

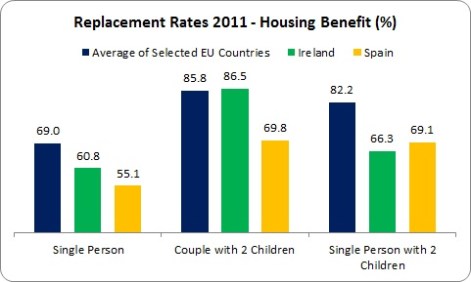

European Comparisons

Let’s

compare the replacement rates for EU countries with much lower unemployment

rates than ourselves: Austria (4.3

percent unemployment), Netherlands (5.3 percent), Germany (5.5 percent),

Belgium (7.6 percent) and Finland (7.7 percent); Ireland had an unemployment

rate of 14.7 percent and Spain’s rate was 21.7 percent. If the disincentive to work argument works,

we should see those countries with relatively low unemployment to have much

lower replacement rates than Ireland and Spain.

What do we find?

We see that, with no housing benefit (e.g. rent supplement),

Irish and Spanish replacement rates are below the average of the selected EU

countries – in the case of the Irish single person, substantially so. When we look at replacement rates including

housing benefit we find:

With housing benefits – remembering that only 11 percent of the

Irish unemployed receive rent supplement –replacement rates are still below

selected EU countries, with the exception of a couple with two children which comes

in at average. Again, Spain lags behind

other EU countries.

None of this shows that ‘high’ replacement rates are an

impediment to taking up work – provided that work is available. And that is the real issue.

Simple Math

There are two simple formulations that undermine the welfare

disincentive argument. First, there are

32 unemployed for every job vacancy in Ireland. Cut social protection and living standards

of jobseekers all you want and this will not reduce that dismal ratio. In fact, it is likely to increase it as

cutting demand will mean even less consumer activity in the economy. The Nevin Economic Research Institute shows

the vacancy rate in other countries which you can access

here (page 33).

And here’s another way to explain unemployment. The last Quarterly Household National Survey

showed that there were 2.171 million in the labour force. There were 1.870 million in employment. Subtract the latter from the former and you

get 301,000 unemployed. That’s the

surplus. How does cutting the incomes of

the surplus increase the number in employment?

This is something that the school of welfare disincentives fail

to address.

The Real Work

How easy it is to look at a problem and say ‘cut it’. High unemployment? Cut wages, cut social protection. It saves one the hard work of addressing the

real problems – namely, the low demand for labour. But even if we focus on the social protection

regime itself, there is still the hard work of putting forward concrete

proposals. One could start with the Citizen

Information Board’s submission on the topic. They highlight a number of key areas where

work, social protection and taxation interact to create income, poverty and

unemployment traps – particularly in the areas where people are trying to

combine part-time / atypical work and social protection.

Working hours

criteria: unemployment payments for

part-time workers are calculated according to days, rather than hours. Someone who gets 10 hours’ work per week is

treated differently if it the work is spread out over five days as opposed to

two (in the former, they get no social protection payment).

Rent Supplement: the withdrawal of Rent Supplement for anyone

working in excess of 30 hours per week can act as a trap. Some kind of transition period – a tapering

over time or over hours – would facilitate this, as would an earnings disregard.

Family Income

Supplement: people must work at

least 19 hours a week to be eligible for FIS.

This, along with the administrative delay of up to several months before

payment is approved, discriminates against part-time work.

Universal Social

Charge: income below €10,036 is

exempt from the USC. But once it exceeds

that threshold, the USC is charged on all income – creating a step effect. This was introduced by the current

Government.

In-work costs: costs as travel and, especially childcare,

makes it costly to take up work. Travel

costs range between €15 and €25 per week, while childcare costs are one of the

highest in the EU.

Co-habiting couples: currently cohabitating couples are treated as

a couple for the purposes of social protection but on moving to employment,

cohabiting couples are not jointly assessed and do not benefit from the

‘married persons’ tax credits system.

Administrative Delays: Delays in processing applications means

people have to manage on inadequate income – below what they were getting on

social protection – while awaiting their payment. This makes it difficult for people to take up

temporary work.

These and a myriad of other issues impact those in low

incomes. People want to work. When it is available, they’ll take it. Even if this means they suffer some of the

difficulties above. Yet the debate is

dominated by those who, ignorant of what life is like at the cutting edge of

unemployment, poverty, atypical work and social protection regulations, make

sweeping comments about ‘disincentives’ and call for social protection payments

to be cut.

What Is Never

Mentioned

As this post has gone on long enough, I won’t go into too

much detail about the flip side of the equation – are social protection

payments too high or are wages too low?

If one wants to ‘make work pay’,

then we need decent wages. Again, just

some quick comparisons in two low-paid sectors – how much of a pay increase (in

PPP which removes living standard and currency variations) would Irish

workers need to reach different EU averages.

Ireland lags well behind EU averages in both main low-paid

sectors. In the wholesale / retail

sector, Irish workers would need a pay increase of between 15 and 32 percent

just to reach the average of other EU-15 countries and small open economies

respectively (the other small open economies, which is our peer group as they

are small economies reliant on the export sector, are Austria, Belgium,

Denmark, Finland and Sweden).

In the hospitality sector – hotels, restaurants and pubs –

Irish workers would need similar increases to reach the EU averages: 13 to 31 percent.

So the question that should be put on the agenda is whether

wages are too low, especially in the low-paid sectors. This is all the more urgent when one notes

that over 27 percent of households with one income suffer

multiple deprivation experiences.

* * *

Social protection payments are not a disincentive to

work. Lack of jobs is a disincentive to

work. If we want to help people – rather

than hector or label them (e.g. ‘life-style choice’) – we need to raise the

demand for labour in the economy , raise wages in the low-paid sectors and

create a social protection/taxation system that makes it easy for people to

take up work. We need to provide

supports – especially affordable childcare – rather than engage in comfortable

armchair lecturing.

And we need to a fact-based debate. That would be of benefit if only to spare us so

much nonsense about welfare disincentives to work.

Leave a comment