Understandably, in this referendum we are focused on the impact of the Fiscal Treaty on Ireland. But this is a Treaty for the Eurozone and the entire EU (with the exceptions of the UK and the Czech Republic, which are pursuing their own home-grown austerity policies). The Government has made much about how the Fiscal Treaty will introduce ‘stability’ and ‘confidence’ in the Irish and European economies. So what might we expect from this unique experiment in simultaneous austerity and how might it impact on an open economy like Ireland. Will the Fiscal Treaty actually result in ‘stability’ and ‘confidence’?

Not according to the Institute for Macro-economic and Economic Research (IMK) based in Germany. They teamed up with other research institutes in Austria and France to assess the impact of the Fiscal Compact on Eurozone and EU growth. And the numbers are not good.

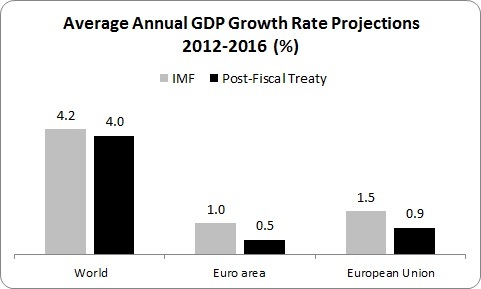

The IMF is already projecting that Euro area and EU growth rates will be well below world growth rates. In a post-fiscal treaty scenario, the IMK projects that European growth rates will be cut further – with Euro area growth rates falling to an insipid ½ percent average annual growth rate.

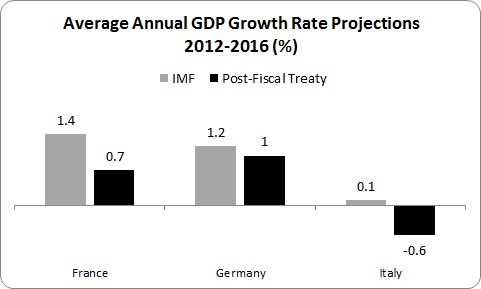

The IMK also looks at specific countries.

It might surprise some that Germany – the ‘engine of the Eurozone economy’ – is already projected to be a low-growth economy under the IMF projections. Even by 2016, the IMF expects the German economy to grow by a mere 1.3 percent. However, given that Germany doesn’t have a significant structural deficit issue, the impact of the fiscal treaty will lower growth only marginally.

However, when it comes to France – which does have a significant structural deficit problem – we see that a low-growth economy will find its growth rate cut in half by the Fiscal Treaty. As for Italy which, like Germany, doesn’t have a significant structural deficit issue, average growth rates fall into negative territory – from an IMF projection which shows them already flat-lining.

The IMK projections for Ireland don’t really work well because they assume all countries the Fiscal Compact would be implemented will meet the structural deficit target by 2016, whereas Ireland may get more leeway coming out of a programme. However, if we assume that Ireland must meet the structural deficit target what might we expect?

I have assumed that a further €5.4 billion fiscal adjustment would be necessary to close the structural deficit gap by 2017 (€5.4 billion being the gap in 2015). This adjustment is to start in 2015. What we find is that GDP growth stagnates at 2014 levels – with implications for unemployment (which the IMF already estimates at over 10 percent in 2017 with a growth rate in excess of 3 percent), incomes and living standards.

And if the Irish growth rates still look better than other countries in the post-fiscal treaty scenario, we always have to remember that GDP is flattered by a multi-national sector which books profits here and then immediately takes them out of the country in what is essentially an accounting exercise.

So all of this is supposed to instil ‘confidence’ and ‘stability’? Cutting growth rates even further in Europe which is already looking forward to a low-growth medium-term scenario – far below world growth rates? How does this promote the confidence necessary to increase investment – when domestic demand is being cut in a number of countries simultaneously? How does this stabilise public finances when economies are going to find it even more difficult to generate the revenues necessary to repay debt? And what happens to all this math if Spain falls into bail-out?

For the Government this is a special problem. Their recovery strategy is based on an expanding export base. However, if European countries are simultaneously driving down their demand, our markets for exports will be contracting. How does reduced demand in Europe impact on our real export growth.

This is not a drive to promote ‘confidence’ and ‘stability’ – this is a dangerous experiment that will produce even greater uncertainty.

This is a recipe for extending and deepening stagnation.

But, hey, at least we’ll be doing it together. As they say, misery loves company.

Leave a comment