Let’s play a game. Let’s auction off a Euro coin. These are the rules. The Euro goes to the highest bidder. The losing bidder, on top of losing out, has to pay the highest amount they bid. So, the first bid is for 1 cent, hoping to make a 99 cent profit. The next bid is for 2 cents, as a 98 cent profit is still desirable. Similarly, another bidder may bid 3 cents, making a 97 cent profit. In this way, a series of bids is continued. However, a problem arises as soon as the bidding reaches 99 cents. Supposing that the other bidder had bid 98 cents. They now risk losing the 98 cents or bidding a Euro even, which would make their profit zero. After that, the original bidder has a choice of either losing 99 cents or bidding €1.01, and only losing one cent. After this point the bidders continue to bid the value up well beyond the Euro. Not only does neither profit, both lose. And as long as they keep bidding, they will lose even more. Until someone accepts the game is up and stops.

Some commentators over the weekend tried to provide solace – that as a result of the Central Bank stress tests the final bank bail-out figure won’t be €27 billion as feared but rather less, only €18 billion to €20 billion. We are bidding well beyond the Euro and every time we bid up, we stand to lose more.

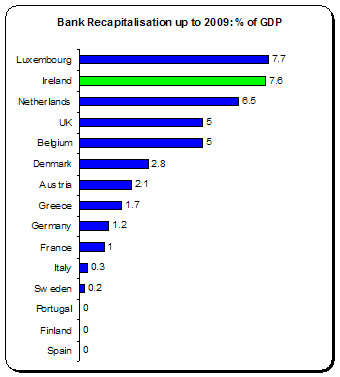

It is often helpful to put these things in international perspective. From an IMF working paper we can compare the cost of the bank recapitalisations to different countries.

Ireland and Luxembourg ae leading the bail-out stakes. But this table only accounts for recapitalisations acutally made by the end of 2009. A number of countries made commitments that were not used up by that date. For instance, the UK was committed to another 3 percent of GDP, as was Austria and Belgium. But further commitments didn’t equal the amount of recapitalisation paid.

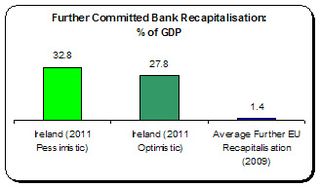

At the end of 2009 the average EU commitment to further bank recapitalisations was 1.4 percent. Between 2009 and today, maybe there was more committed. But whatever the amount, it pales into nothing compared to Irish commitments.

In anticipation of the new commitments arising from the stress tests, Ireland could face further recapitalisation costs of 33 percent; but if the more optimistic figures emerge, only 28 percent. Such is the desultory search for the silver lining.

In anticipation of the new commitments arising from the stress tests, Ireland could face further recapitalisation costs of 33 percent; but if the more optimistic figures emerge, only 28 percent. Such is the desultory search for the silver lining.

[Note: This doesn’t count the senior bondholders under state guarantee, which are worth another 12 percent of GDP. And this doesn’t count ECB liquidity. And this doesn’t count NAMA.]

Is there any rational justification for piling this amount of potential bank debt on to sovereign debt? Clearly, by 2009 no one could claim that the Irish public had not shouldered more of a burden than almost any other state – and that was when the burden was 7.6 percent of GDP.

Do we have to take on board another four or five-fold to show we are good Europeans? Are we working to a cunning plan that no one knows anything about? Or are we stuck in a Euro auction? Are we just doing this thing because we are doing this thing?

It’s time we stop, take a step back from this madness and ask the simple question: is there a better, more economically efficient way of saving our banking system than this? It’s a reasonable question and if we have to put bank payments on hold for a few months the sun will still shine tomorrow – in Dublin, in Brussels, in Frankfurt. And if we find a better way, then everyone will win – Irish taxpayers, EU taxpayers, the Eurozone itself.

It’s time we stop the bidding. Yes, we’ll end up losing whatever we have bid so far. But if we continue, the stakes will get higher and higher and the prospect of recovering our bid will diminish further.

Until we go broke.

Leave a comment